Jefferson Airplane live, 1968: while it lasted, theirs was a glorious run, with truly timeless music left in the wake of a shabby final chapterThe Odyssey Of Their Flight

By David McGeeLIVE AT THE FILLMORE AUDITORIUM

10/15/66 LATE SHOW: SIGNE’S FAREWELL

Jefferson Airplane

Collectors’ Choice MusicLIVE AT THE FILLMORE AUDITORIUM

10/16/66 EARLY & LATE SHOWS: GRACE’S DEBUT

Jefferson Airplane

Collectors’ Choice MusicLIVE AT THE FILLMORE AUDITORIUM

11/25/66 & 11/27/66: WE HAVE IGNITION

Jefferson Airplane

Collectors’ Choice MusicRETURN TO THE MATRIX 02/01/68

Jefferson Airplane

Collectors’ Choice MusicSETLIST: THE VERY BEST OF THE JEFFERSON AIRPLANE LIVE

RCA/LegacyIt appears the Jefferson Airplane has yet again taken off. Four new live albums from Collectors’ Choice (the RCA/Legacy Setlist title being not a single show but a collection of essential tracks culled from shows during the band’s prime, 1967-1972) largely tell the story of the onstage Airplane’s evolution from a time when it was one of San Francisco’s most popular bands (at a time when San Francisco was producing world class rock ‘n’ roll bands determined to push rock ‘n’ roll’s boundaries) to the moment it reigned as the finest American rock ‘n’ roll band extant. Live albums are not new to the Airplane catalogue—there are at least five preceding these, including the At Golden Gate Park import—and some of the tracks here will be found on the earlier releases, but what Collectors’ Choice has made possible, for those so inclined, is a chance to hear an important band grow and use its bully pulpit of the stage to take themselves and their fans on musical odysseys during the course of a single set, reimagining the familiar songs in ways that respected the originals’ most appealing qualities, taking chances with vocal arrangements in a search for fresh lyrical textures, giving the superb musicians greater rein to subvert the traditional song structure with daring, jazz-influenced theme and development jams, and, even on their sloppy nights, never offering less than high-octane intensity in their drive to take everything and everyone higher.

Kudos to the Collectors’ Choice Music team for assembling this smart chapter in an important band’s history. Perhaps a younger generation of rock fans does not remember that the Airplane always had a female vocalist, but it was not always Grace Slick. Signe Anderson, with a solid folk background, was the original trilling distaff voice to group founder/lead singer Marty Balin’s unusually expressive tenor leads, which could be, in one instance, soothing and sensuous, and in another, fiery, piercing, astringent, angry.

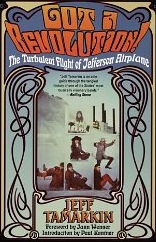

“The voice glides easily, swoops and swirls fluidly, playing with the lyric in a nonlinear, often surprising manner. It’s a smooth, flexible voice, unabashedly alluring without being schmaltzy. Balin’s mastery of dynamics is fully formed; the honey in his voice is as sweet as it would ever be. Yet there is a toughness behind it too, as if the singer had been around the block a few times more than he’s letting on.” —Jeff Tamarkin, on Marty Balin’s singing on the solo recordings he made pre-Airplane. From Tamarkin’s definitive history of the Airplane, Got a Revolution! The Turbulent Flight of the Jefferson Airplane (Atria Books, NY. 2001)

Jefferson Airplane with lead singer Signe Anderson, ‘It’s No Secret,’ Fillmore Auditorium, 1966, with light show

The first album in the Collectors’ Choice retrospective documents Signe Anderson’s final performance with the band, on October 15, 1966, in what was the second of a three-night stand at Bill Graham’s Fillmore Auditorium; the next evening Grace Slick made her Airplane debut. The era straddling nature of this near-hour-long set makes the Signe’s Farewell CD an interesting artifact in Airplane history. By this time Balin had written “3/5th Of A Mile In 10 Seconds” and this indelible track from what became the band’s monument, Surrealistic Pillow, is the second song of the night, following the nine-minute opening psychedelic jazz jam (which in and of itself shows the remarkable guitar-bass dialogue that was developing between Jorma Kaukonen and Jack Casady)—but here it’s done in the jamming style of the SF bands, and turns into a near-six-and-a-half-minute opus, a grinding, moaning, even bluesy discourse in contrast to Pillow’s amphetamized version. Anderson, however, is not much of a factor on her last night in the Airplane hangar. It has become Marty-Jorma-Jack-Paul Kantner’s band (Skip Spence was the drummer at this time, and would remain so through Surrealistic Pillow until he left to form Moby Grape and write his name tragically, both personally and professionally, in rock ‘n’ roll lore); the sonics are turning harder and grittier than the folk-rock stylings heard on its debut album, 1966’s Jefferson Airplane Takes Off. From that album, Balin and Anderson get together in the old style on a lovely, lilting love ballad, “Come Up the Years,” Anderson’s soft tone adding a gently yearning underpinning to Balin’s plaintive pleading; the soulfulness of their vocal interaction recalls what Balin said to the San Francisco Chronicle’s legendary music critic Ralph J. Gleason, as recorded in Gleason’s liner notes for Takes Off: “All the material we do is about love. A love affair or loving people. Songs about love. Our songs all have something to say, they all have an identification with an age group and, I think, an identification with love affairs, past, beginning or wanting…finding something in life…explaining who you are.” Immediately following “Come Up The Years” is one of the band’s then-staples, and Anderson showcase, the propulsive “Go To Her,” on which Anderson and Balin simply soar—take off, if you will—over the twisting, serpentine, steely guitar lines Jorma crafts as the rhythm section punches out a hard driving beat. Amazing, though, how much Anderson sounds like Slick (or vice versa) on this tune, but regardless, it’s the sound of a band shedding its old skin for something more striking and more lethal than its former conventional garb (see the conservatively attired sextet on the back cover photo of Take Off for reference).

Jefferson Airplane, ‘Chauffeur Blues,’ Signe Anderson’s showcase piece, originally recorded by Memphis Minnie, as heard on Jefferson Airplane Takes Off (1966)

Signe Anderson

Ten songs in Balin announces Anderson’s imminent departure, the crowd immediately starts hollering for “Chauffeur Blues,” from the first album, and immediately the band is into this stomping frolic (written by Lester Melrose and originally recorded by Memphis Minnie) with Anderson alone on lead and wailing it like she was a born earth mama, swaggering and sultry all at once, inspiring in Jorma his most sensuous, screaming solo of the night as a response. (FYI: Airplane buffs will note the presence in the set list of Donovan’s luminous, woozy “Fat Angel,” a song he wrote after being smitten by the Airplane and in which he—through Paul Kantner, who takes the lead vocal—muses, “Fly trans-love airways, get you there on time…Captain High at your service…”).

Grace Slick and her brother-in-law Darby Slick were then playing in the Great Society, another up and coming San Francisco band, and she knew some of the Airplane musicians. When the Great Society fell apart, Jack Casady invited Grace to step over to the Airplane and, according to Jeff Tamarkin, “it didn’t take more than a minute for her to answer.” Why Anderson left in the first place remains in dispute: in Tamarkin’s account, both Balin and Airplane manager Bill Thompson assert she was fired, for various reasons; Anderson says she left of her own accord, telling Tamarkin: “I never wanted to leave, but I had another priority, my husband and my child. People always think that sounds really corny and dumb. They say, ’But you were finally making it.’ And I say, ‘If you have nothing left when you’ve gotten there, then why bother to take the journey?’”

In his book Tamarkin did justice to Anderson’s contribution to the Airplane’s success, though, and her performances on the Farewell disc prove she was no extra appendage: she sang great, she had presence.

“She’d had a good run. Although her tenure with the Airplane lasted barely more than a year, Signe had earned her part of the rave reviews. She’d been there for the band’s first album, and all of those landmark gigs. She had a strong fan following. She’d even been immortalized, along with the rest, on a Bell Telephone Hour TV special on the San Francisco sound. By the time that program aired, though, the Airplane had a new female vocalist.” (Tamarkin, p.105)

And from there, as per these CDs, the Airplane story settles into the personal, litigious and musical dramas of Slick, Kantner, Balin, Kaukonen, Casady, and drummers Spencer Dryden (1966-1970) and (on the Legacy Setlist disc) Joey Covington (1970-1972). As for the personal and litigious, suffice it to say the Airplane had its share of internal romantic entanglements and as the years wore on the various parties found sometimes ingenious ways to sue each other for various reasons (one lawsuit even had Paul Kantner in the odd position of suing himself). Regarding the musical narrative, the remaining discs capture a band on its upward arc of creativity, inspiration and influence. By the end of the Collectors’ Choice discs, in 1968, and the Legacy live disc, in 1972, we hear one of the most important of all rock ‘n’ roll bands in full flower. The history post-1972 is not so glorious, but that’s another story, blessedly omitted from this collection.

David Crosby: When they got Grace in the band, that was just beyond belief. She was stunning. She had a power and intensity onstage that Stevie Nicks should only ever dream she could get. With Marty, she was like a bullfighter with a bull. She would circle him and dart at him and pull from him and electrify him and touch him with bare wire. And Marty rose to the occasion.

Marty Balin: She was just like we were: drugged out, drinking, free and ballsy and outrageous. She just fit in great.

Paul Kantner: She was coming into a pretty well-gelled situation. A lot of people were angry. There was a whole Signe contingent, among RCA as well, who were really fond of her. I was too; I thought Signe was a great singer. And Grace always stood in awe of her. So when Signe left there were a lot of people saying, “Oh, my god, the Airplane is dead.”

Jack Casady: Grace would lead us different directions. I could play a lot more aggressive bass lines than I could to some of the things that Signe would do, which were much more folk-oriented. Here was something I could put my teeth into.

Grace Slick: Our voices together were a tag team kind of thing. Marty would be singing and I’d do something else off the top of that and Paul would be somewhere else underneath. It was a little sloppy, actually, it wasn’t precise, but it was fun because you could do anything you wanted to. It wasn’t like, how come you didn’t sing that flatted fourth?

(Tamarkin, pp. 113-114)Jeff Tamarkin observes the tentativeness in Grace Slick’s early Airplane appearances (“the forceful personality and the improvised vocals were initially kept in check”), but also notes: “It didn’t take long for [her] to find her place, and to learn how to apply her technique to the Airplane’s repertoire.”

October 16, 1966, the day after Signe bid farewell to Airplane fans, Grace strode onto the Fillmore stage as the band’s new lead singer, the moment captured on the Grace’s Debut disc of the Collectors’ Choice release. The tentativeness in Grace noted by Jeff Tamarkin is evident on the live recording pieced together from early and late shows that night. Which is not the same as saying it’s a dull show. Far from it. If you heard it in real time when it happened, it was likely a rousing night. But there is a restraint evident in the playing and the singing both that would soon be a thing of the band’s past. At the start, it seems as if the Airplane didn’t want to let go of the Signe era, opening with two folk-flavored tunes: Dino Valenti’s “Let’s Get Together,” which would later become The Youngbloods’ signature song as “Get Together” but had already been recorded by the Kingston Trio and We Five when it was covered on the Airplane’s debut album in a Byrds-ish arrangement with Kantner’s jangly12-string guitar dominating, as it does on this live version in which Grace takes a decidedly low-profile harmony vocal in the straightforward arrangement; and from the group’s earliest days, Fred Neil’s “The Other Side of This Life,” which opens with two minutes of free-form jamming before Marty and Grace enter vocally, and the latter seems to pull back into a subservient vocal role to Balin, when only a few months from this time she would be behaving towards Balin exactly as David Crosby described her to Tamarkin: circling, darting, pulling, electrifying, touching him “with bare wire.” If Signe’s farewell performance captures the group in transformation, Grace’s debut feels more like a group in transition, revisiting its roots in the abovementioned cover songs (and in a gritty, grinding, blues-drenched take on “Kansas City” that serves as another electrifying solo turn for an inspired Jorma, who practically offers a short course in blues guitar styles—from single string runs to double stops to wild chordal bursts—when he’s not capturing the old ennui effectively in his laconic vocal) and stepping forward with original material—the strutting “Bringing Me Down” (a Balin-Kantner tune); Balin-Kaukonen’s wrenching blues ballad, “This Is My Life,” with Balin’s emotional vocal betraying his command of the blues vocal idiom and Jorma adding instrumental shadings alternately rueful and aggrieved, cued to his singer’s mood; a wild, anything-goes, 10-minute jam, “Thing,” sparked by the diversity of tones and temperaments Jorma coaxes out of his guitar and a totally unpredictable Casady bass solo that keeps building in intensity as drummer Spencer Dryden joins the fray with a galloping rhythmic response; and a full-bore guitar and vocal attack on “3/5 of a Mile in 10 Seconds,” although once again Grace is alternately asserting herself and laying back where she would later charge ahead and push Balin harder.

This was but prelude for the new lineup. Fifteen days after this show, on October 31, 1966, in a recording studio in Los Angeles, the Airplane recorded a new Balin/Kaukonen tune, psychedelic music’s Rosetta Stone, “She Has Funny Cars,” and “Today,” a tender, swaying Balin/Kantner ballad. There was no hesitation now on Grace’s part—she came to the sessions, Tamarkin says, “full of ideas and vigor.” And on “She Has Funny Cars,” which became the lead track of the resulting long playing album, she put the cap on the Signe Anderson era for good by making a statement such as her predecessor had never done and which had the effect of marking the Airplane as a rock ‘n’ roll band of vision and daring, ready to ascend to exalted heights. “A few solitary bass notes, and the tempo shifts to a light swing. Marty and Paul engage in a call-and-response with Grace, but instead of echoing them she sings a contrapuntal lyric dissociated from the main storyline. Soon she zooms up and away, no longer singing words at all but expounding on a pure note, increasingly intense, cutting through everything in its path. Occasionally she meets them on common ground: ‘And I know, and I know, and I know, your mind’s guaranteed, it’s all you’ll ever need, so what do you want with me?’” (Tamarkin, pp. 115-116)

Working with producer Rick Jarrad, the band recorded Surrealistic Pillow in 13 days (cost: $8000). In December 1966 the Airplane was featured in a Newsweek article examining the burgeoning San Francisco music and cultural scene; on January 14, 1967, the group joined fellow SF icons the Grateful Dead and Quicksilver Messenger Service to provide music for the Human Be-In all-day celebration in Golden Gate Park, a run-up to the “Summer of Love.” In February, Surrealistic Pillow was released, and suddenly the world was the Airplane’s oyster: the group was on TV (American Bandstand—whose host, Dick Clark, asked Paul Kantner if parents should be worried now that young people were embracing groups such as the Airplane and stood stunned as Kantner responded: “I think so. Their children are doing things they don’t understand.”—Smother Brothers, Ed Sullivan, Carson’s Tonight Show), played the Monterey Pop Festival in June, toured everywhere, were being paid unheard of sums—anywhere from $3500 to $15,000 a night—to play their music in public. Voila! Rock royalty of the first order. Amazingly, for all the sexual, pharmaceutical and legal shenanigans going on with and around them, the band didn’t blow it. With its lineup stable into 1970, Jefferson Airplane continued making good music.

Jefferson Airplane on American Bandstand, introduced by Dick Clark. ‘White Rabbit,’ ‘Somebody to Love’“With Surrealistic Pillow completed, the Airplane went home to play Thanksgiving weekend at the Fillmore.” (Tamarkin, p.120)

That something remarkable had happened to the Jefferson Airplane during its 13 days in a Los Angeles recording studio was not so much evident on its set opening version of “Plastic Fantastic Lover” on the first of two nights at the Fillmore, November 25, 1966, as heard on the two-disc Live At The Fillmore Auditorium 11/25/66 & 11/27/66: We Have Ignition, but it certainly was at about the two-minute mark of the second number, “High Flyin’ Bird,” the Billy Edd Wheeler number recorded for the band’s first album. In short, what happens here is Grace stepping forcefully into her role, bringing to bear the passion and improvisational fire she had honed during the Pillow sessions in this live performance, when she challenged Marty—you don’t even have to be familiar with the Airplane’s music to sense something exceptional going on in the consuming heat of the duo’s sparring as the song surges to its close. Finally, Paul introduces “a song from an album we just finished,” and Jack’s halting solo bass line introduces Kantner’s “DCBA-25” (as Tamarkin notes, the title refers in part to the song’s chord structure, with the 25 a nod to a certain batch of Paul’s preferred acid, LSD-25). Even though Grace wobbles off-key slightly near midpoint, the Airplane’s new polish must have been striking, if not startling, to Airplane fans (who might also have been wondering if their beloved local bards were in thrall to L.A.’s Byrds, given the jangly, folkish nature of the arrangement). Regardless, this is a moment; not to make too much of it, but from the vantage point of time, it sounds like a demarcation point, the final, complete break from the original blueprint with Signe Anderson to the fruition of a vision that came into focus when Grace stepped on this same stage a little more than a month earlier, a neophyte Airplane newcomer then, now one with wings unfurled, gliding effortlessly and beautifully in her own jetstream. This is not to say the Jefferson Airplane of Thanksgiving weekend 1966 was the Jefferson Airplane of two years, three years later; despite the noticeable progress towards a tighter sound and arrangements, some distracting loose ends remain in the performances, such as Grace stumbling off-key vocally, albeit fleetingly. But clearly something has changed, and for the good. The Pillow material is performed close to the arrangements worked out for Surrealistic Pillow, but the earlier material finds the musicians taking more latitude in crafting lively instrumental dialogues as introductory passages—as on the first 1:30 of a more deliberate treatment of Fred Neil’s “The Other Side of This Life” (from the first show) than was presented on Takes Off. The first show also captures a rare live performance of another Skip Spence song recorded for Pillow but left off the album, an affecting, multi-layered, acoustic-centered ballad of unrequited love, “JPP McStep B. Blues.” The 11/25 set also includes the first Airplane performance of a song that was familiar to fans of the Great Society, Grace’s “White Rabbit,” altered from her previous band’s treatment into the song she heard in her head when she wrote it.

There had never been another song like “White Rabbit.” Originally called “White Rabbit Blues,” it was Lewis Carroll meets Ravel meets Sketches of Spain. Electric guitars and snare drums piled atop one another, blatant drug allusions crossed paths with bedtime stories, all climaxing in a smashing crescendo, a bellowing Grace inventing a catch phrase for her generation: “Feed your head! Feed your head!” (Tamarkin, p.110)

What the fans at the Fillmore heard during the Airplane's two-night stand was “White Rabbit” as it had been transformed for Surrealistic Pillow: In the hands of the Great Society, Grace’s showpiece had been a gypsy trance dance. An extended instrumental section reminiscent of the Butterfield Band’s East-West preceded the body of the song. It had an insistent tempo, marked by rocking drums and a repetitive guitar line. The Airplane slowed it down and stripped the ornamentation away, kept the core melody and restored to the song the bolero rhythm that Grace had envisioned. Jack wrote a new, funky bass part, Spencer stayed close to his snare and Jorma played a bold, seductive, yet simple guitar line that transforms smoothly into chunky, aggressive chords in the choruses. Grace, of course, was the focus and she delivered a commanding, no-nonsense vocal performance devoid of her trademark improvisations. What had begun as an allegory became an anthem for a generation.

Marty Balin: It was a masterpiece, really. Perfectly written for the perfect time. (Tamarkin, pp.117-118)

Oddly, Darby Slick’s “Somebody To Love” (originally recorded by the Great Society), Pillow’s other anthemic song, at least as famous, if not as notorious, as “White Rabbit” (it charted higher, in fact, at #5 to the latter’s #8) is notably absent from the 1966 Fillmore performances.

Jefferson Airplane, ‘Volunteers,’ Woodstock 1969

Jefferson Airplane, ‘3/5th of A Mile in 10 Seconds,’ Woodstock 1969

Marty and GraceNot so a little more than a year later, when the Airplane returned to the venue that had become its home in the early days, a place where they began to gel into a serious band and find their collective voice: the Matrix. Until Jack Casady joined the lineup, in fact, it was the Airplane’s home. “The club had been designed with them in mind, they were able to fill the room to capacity each time they played (which wasn’t difficult as it didn’t hold much more than a hundred bodies) and they liked the place.” (Tamarkin, p. 50) As captured on the final disc of the Collectors’ Choice set, Return To The Matrix, 02/01/68, the set opening version of “Somebody to Love” perhaps explains why it’s not on the double-Fillmore disc. To begin with, Grace isn’t even sure what the first number is—she says, “The first song is either ‘Somebody to Love’ or ‘Wild Time.’” Upon which Jorma begins crunching out “Wild Thing” chords, and after a few seconds of un-Airplane-like sludge, Grace begins singing, but something is drastically off. No matter how hard Grace works—and she’s digging in, trying to pull the band out of its malaise with some gut wrenching vocal pyrotechnics foreign to her usual style. But tthe song is caught in musical quicksand. It’s not going to fly. Then, at the three-minute mark,Grace howls, “Find you somebody to love,” Marty starts bashing the tambourine in time, Jorma tears off a trembling, nervous lead run and it takes off, Grace ad-libbing a preacher's perorations (“Let ‘em love ya! That means open up!”) and Jorma feeding off her drive, note by stinging note crafting a piledriving solo that becomes a remarkable segue into the following “Young Girl Sunday Blues” in the way the spark from his soloing carries over into Marty’s edgy, pleading vocal, the fire from Marty’s mesmerizing performance subsequently fueling a hard charging version of “She Has Funny Cars,” from Pillow, done at a faster tempo than the album track, mainly, it seems, because the band was now riding its own wave, oblivious to any set patterns carrying over from the Pillow sessions, out there free and unfettered, speaking the musical language they instinctively understood as one and remaking the old models, which were mostly less than two years old and some, such as a tender, pastoral Paul Kantner song, “Martha,” written for the band’s next album, still in the gestation stage. The early Airplane is summoned only in Jorma’s tough, snarling take on “Kansas City” and the foreboding miseries Marty Balin and Skip Spence chronicled in “Blues From An Airplane,” from Takes Off, which here serves as an odd, downbeat set closer. Maybe the Airplane had simply outgrown the Matrix by this time, but whatever was happening on the night captured here was hardly a portent of the greater things to come over the next two years and right up to 1971’s Bark, when the principals became more outspoken politically, even as Kantner began exercising his fascination in interstellar travel in song (he released a solo album in 1970, Blows Against the Empire that was credited as being by Paul Kantner/Jefferson Starship), while long simmering personal differences and other shenanigans and near-tragedies began shaking the foundation. In 1970 Kantner and Slick were in a personal relationship that produced a child the following year, by which time a long-disillusioned Balin—battling an alcohol problem and being a clique of one on the outside of the Kantner/Slick and Casady/Kaukonen axes—had left the band. On May 13, 1971, Slick was nearly killed when her car plowed into a wall near the Golden Gate Bridge entrance, which rendered moot a year’s worth of recording and touring plans. There would be occasional reunions, new formulations of Starship lineups, but the Airplane was effectively mothballed after Bark. Theirs was, while it lasted, a glorious run, with truly timeless music left in the wake of a shabby final chapter all too common to rock ‘n’ roll lore. But oh how they flew.

Jefferson Airplane, ‘Somebody to Love,’ live at the Fillmore Auditorium 1968

So ends the fruitful years chronicled on six CDs in four packages courtesy Collectors’ Choice. Legacy’s Setlist collection is a reliable live overview of in the greatest hits mold, and does not disappoint. Some of the songs, of course, overlap with those on the Collectors’ Choice set, but not the performances, and two tracks here are previously unissued: a tense, riveting version of “White Rabbit” from a November 26, 1966 late show at the Fillmore—with the drama supplied as much by Jorma’s flinty, aggressive guitar as it is by Grace’s powerhouse vocal—and another Fillmore performance, from February 6, 1967, of “It’s No Secret,” a wild and woolly rampage of assaultive rhythm, spiky guitar and lung busting vocals by Marty and Grace, who challenge each other in a way that adds near-unbearable intensity as they race towards the song’s end. What’s here that is not in the purview of the Collectors’ Choice discs is the late ‘60s-early ‘70s material—Jorma taking a dry, drawling vocal on “Feel So Good” (Winterland, 1972); a fierce, rousing “Volunteers” (a song that has aged better than many would have thought at the time and ought to find new resonance with a new generation, if anyone was paying attention) from the Fillmore East in 1969, with its dynamic vocal byplay between Grace and Marty, who never sound less than utterly invested in their high-minded rhetoric; and from the same Fillmore East performance that begat “Volunteers,” a 10:27 version of Paul Kantner’s “The Ballad of You And Me And Pooneil,” the latter name in the title being a fusion of what author Jeff Tamarkin calls “Paul’s greatest inspirations, A.A. Milne’s lovable bear of children’s literature, Winnie the Pooh, and folk singer Fred Neil.” True to the recorded version, the live version begins with a blast of feedback from Jorma, opens out into a brisk stomp, then settles into a long improvisational section that gives wide latitude to Cassidy for a discursive bass solo that builds in intensity as he moves up the neck and plays around with the rhythmic structure before Grace and Marty return and Jorma cuts out on some freewheeling solos behind them. As Tamarkin says of the recorded version, so it is true of this astounding live track: “There’s a new freedom to the sound that was missing from the carefully manicured and pristine sounding Pillow. The playing is loose, carefree and improvisational…” Incendiary versions of “She Has Funny Cars,” “Somebody To Love,” “Plastic Fantastic Lover” are riveting moments, and Marty’s beautiful, aching ballad from Surrealistic Pillow, “Comin’ Back To Me” (complete with the winsome flute part), inspires both a wondrous, tender Balin vocal in which he caresses his lyrics with the kind of late-night sullenness Sinatra brought to his saloon songs and makes room for an extended, meditative instrumental improvisation on the lovely melody. Yes, if you want only one Jefferson Airplane live album, a case can be made in favor of the Setlist title, but bypassing any one of the Collectors’ Choice titles is to miss some of the best rock ‘n’ roll made on these shores in the 1960s. To those of a certain generation, this translates to missing some of the best rock ‘n’ roll ever made, period. Your call, dear readers.

Jefferson Airplane, ‘The Ballad of You And Me And Pooneil,’ from ‘A Night At the Family Dog,’ February 1970

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024