‘Get out of the medieval witted sepulchers, and face your fears. I know very well it is not easy.’

Leo Tolstoy died one hundred years ago this month. The moral and religious questions he was pondering then resonate still. Herewith, in remembrance, his timeless short story, ‘The Three Hermits’

One hundred years ago this month, on November 20, 1910, the great Russian author/essayist/dramatist/religious philosopher/educational reformer Leo Tolstoy died of pneumonia at Astapovo station. Then 82 years old, a member of the Russian nobility, he had left home in the dead of winter after making a decision to abandon his family and his inherited wealth—wealth he always felt undeserving of—and embrace the life of a wandering ascetic. Two years before his death he had initiated what became an intense one-year correspondence with Mohandas Gandhi, who had been persuaded by Tolstoy's 1892 essay, “The Kingdom of God Is Within You,” to embrace a path of nonviolent resistance. A vegetarian and pacifist, Tolstoy condemned the Russo-Japanese War of 1904 and was a staunch supporter of the pacifist Christian Dukhobors, whom he aided in their migration to Canada. This despite his anarchist positions with regard to state and property rights evolving out of his belief that Christians should "reject the State when seeking answers to questions of morality and instead...look within themselves and to God for their answers." (The Anarchist Library). In his view the only possible permanent revolution was "a moral one: the regeneration of the inner man." One of Tolstoy's most profound conversations about his struggle with the meaning of faith in the context of an individual's life was contained in his 1886 short story, "The Three Hermits,” a retelling an old legend popular at that time in Russia’s Volga district.

Priceless footage of Leo Tolstoy, with his family (he had 13 children), on his estate, in death at the Astopovo station house, and being borne in his casket to the funeral Russian authorities condemned as honoring ‘an infidel’ but were powerless to stop due to the outpouring of mourners gathering to honor the great Russian writer.Below is an analysis of "The Three Hermits," followed by the complete text of the short story.

Tolstoy’s Three Hermits: An Analysis

Between 1875 and 1877, Leo Tolstoy, nobility by birth, wrote installments of Anna Karenina. While writing Anna Karenina, he became obsessed with the meaning and purpose of life. This led him in 1982 to compose the essay "My Confession," detailing his agonizing religious and moral self-examination. He devoted another three years to the discovery of the meaning and purpose of life. At the close of seven years of only non-fiction essays, Tolstoy resumed writing and publishing fiction. However, he did write two more essays devoted to the meaning of life, “What Then Must We Do” (1886) and “The Kingdom of God is Within You” (1892). In 1886 Tolstoy published a particularly intriguing tale of a bishop and three old men, "The Three Hermits," which reflects the conflicted author’s search for purpose and the meaning of life.

“The Three Hermits” is a journey, both physical and spiritual, similar to Tolstoy's faith journey. "A bishop was sailing from Archangel to the Solovetsk Monastery, and on the same vessel were a number of pilgrims on their way to visit the shrine at that place..." (p.1). The story goes on to say that a fisherman on board relayed the tale of the three hermits who live on an island near where they currently were sailing. The Bishop becomes very curious, and insists upon meeting the hermits. The other pilgrims protest at the idea of stopping. The captain also objects and informs the bishop, "The old men are not worth your pains. I have heard said that they are foolish old fellows, who understand nothing, and never speak a word, any more than the fish in the sea" (p.3). This passage makes an ironic point. The pilgrims travel to Solovetsk, home of a monastery considered one of the holy places in Russia, to pay homage and receive God's favor, yet they are unwilling to learn from people close to God, much like the people of Tolstoy's time, too wrapped up in the church's doctrine to see the way to God. Tolstoy wrote in “Repent ye, for the Kingdom of Heaven is at Hand,” a chapter of “The Kingdom of God is Within You,” that Christians must aspire to the Kingdom of God, not the kingdoms of the world, meaning that the idols and relics of the church are worthless, people should instead visit God through meaningful prayer, good deeds, and work. The tale continues on to say, "the cable was quickly let out, the anchor cast and the sails furled... Then a boat having been lowered the oarsman jumped in, and the Bishop descended the ladder and took a seat" (p.3). This could be interpreted as the bishop being humbled, lowering himself on to the boat. A bishop is defined as an overseer, a supervisor, holding a position one rank over a priest. Therefore, he by going to the island humbled himself. The story continues in the tale by telling of the hermits, how they bowed before him, and the priest's teaching them to pray, the Lord's Prayer, instead of theirs, "Three are ye, three are we, have mercy upon us" (p.4). Upon leaving, the priest in the distance hears them praying. When the island was no longer visible, he relaxed and "he thanked god for having sent him to teach and help such godly men" (p.5). No sooner had he uttered the words than did the Hermits appear running through the water. The three in one voice said, "We have forgotten your teaching, servant of God. As long as we kept repeating it, we remembered, but when we stopped saying it for a time, a word dropped out, and now it all has gone to pieces. We can remember nothing of it. Teach us again." The bishop crossed himself and leaning over the ship's side said: "Your own prayer will reach the Lord, men of God. It is not for me to teach you. Pray for us sinners." And the Bishop bowed low before the men. (pp. 5-6).

Count Leo Tolstoy reads ‘Thoughts from the Book ‘For Every Day,’’ 1980The hermits show a great deal of respect for the church and God, thus, they bow low before the Bishop, as a sign of respect, knowing he is God's servant. This gives him a false idea of superiority, not implied intentionally by the Hermits. However, the hermits have the upper hand. Though they patiently learned the Lord's Prayer and allowed the Bishop to "teach" them to pray, they, in the end, teach him the truth of God and prayer. This point is shown, in that, as soon as the Bishop commended himself, the hermits appeared, and asked him to re-teach the prayer. Matthew 6:7 sums it up: "But when ye pray, use not vain repetitions, as the heathen do: for they think that they shall be heard for their much speaking" (KJV, Matt 6:7), meaning that the hermits had no understanding of the words the spoke, they went along with the "lesson" in the name of pleasing God. However, the prayer they made came from their hearts, which made them closer to God. The Bishop understood this and bowed lower to show the hermits that they were far superior. The walking on water also is a lesson in faith. The hermits possessed such an extreme faith in God, and divine interest in salvation that they could run at incredible speeds across water, as if it were dry land. In the bible, Jesus shows that with faith walking on water is possible.

About three o'clock in the morning Jesus came to them, walking on the water. Then Peter called to him, "Lord, if it's really you, tell me to come toyou by walking on water." "All right, come," Jesus said. So Peter went over the side of the boat and walked on the water toward Jesus. But when he looked around at the high waves, he was terrified and began to sink. "Save me, Lord!" he shouted. Instantly Jesus reached out his hand and grabbed him. "You don't have much faith," Jesus said. "Why did you doubt me?" (New Living Translation, Matthew 14:25, 27-31).

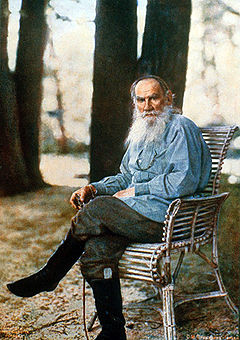

The only known color photo of Leo

Tolstoy, taken at his 4,000 acre

Yasnaya Polyana estate (which

employed 300 serfs) in 1908

by Prokudin-GorskiiTolstoy makes reference to the Trinity, showing a divine presence in his journey. The story says "he saw the three men: a tall one, a shorter one, and one very small and bent, standing on shore and holding each other by the hand" (p.3). According to the Trinity, the father, son, and Holy Spirit are one. Three is also important in that three days after Christ died, he rose again (New Living Translation, Luke 9:22). Noah had three sons (Genesis 5:32). The Bible mentions the number three about 400 times. However, Tolstoy amplifies the image of the trinity in his description of each of the three: "One is a small man and his back is bent. He wears a priest's cassock and is very old; he must be more than one hundred, I would say. He is so old that the white of his beard is taking a greenish tinge, but he is always smiling, and his face is as bright as an angel's from heaven." (p.2). Tolstoy seems to describe either the Father or the Holy Spirit. The priest's garb allows the reader to make a connection between a priest commonly called father and the old man. In addition to being the eldest, he also may be the one considered the father, in that the others look to him for guidance. For example, the bishop asked what they are doing to serve God and save their souls. "The second hermit sighed, and looked at the oldest, the very ancient one" (p.4). Nonetheless, being the eldest he also could be the all-encompassing Holy Ghost. The brightness of his face leads a person to believe he is not of this world, like a spirit. "The second is taller, but he is also very old. He wears a tattered peasant coat. His beard is broad, and of a yellowish gray color. He is a strong man... He is too kindly and cheerful" (p.2). The second hermit represents the Father. God has great strength, enough to bear the weight of the world. The second hermit also has tremendous strength. "The Lord is righteous in everything he does; he is filled with kindness" (New Living Translation, Psalms 145:17). The second, according to the sailor's description is also kind-hearted. "The third is tall, and has a beard as white a snow reaching to his knees. He is stern, with overhanging eyebrows; and he wears nothing but a piece of matting tied around his waist" (p.2). The matting tied around the third's waist is remnant of Christ at crucifixion; the soldiers stripped him of most of his garments, leaving him with enough to cover his waist. Another similarity between the third and the Son is that the third is stern as was Jesus in his adult life.

The struggle to find faith has created an enigma for Tolstoy, brought to life in a fable. “The Three Hermits” span time in understanding the journey to the meaning of life. To this day, the puzzle never has been solved and may never be solved. In the immortal words of Tolstoy, "If you are content with the old world, try to preserve it, it is very sick and cannot hold out much longer. But if you cannot bear to live in everlasting dissonance between your beliefs and your life, thinking one thing and doing another, get out of the medieval witted sepulchers, and face your fears. I know very well it is not easy." (The Anarchist Library, p.1).

Works Cited

Tolstoy, Leo. “The Three Hermits.” Democritus University of Thrace. 8 January 2000

Leo Tolstoy. The Anarchist Library. 12 January 2000 http://flag.blackened.net/daver/anarchism/tolstoy/

Forster, Stephen. The Gulag's Archipelago. 12 January 2000

Crosswalk.com: Bible Study Tools. Crosswalk.com Network. 14 January 2000, http://www.biblestudytools.net

"Tolstoy, Leo." World Book. Chicago: World Book Inc., 1998.

***

The Three Hermits

By Leo Tolstoy

(1886)AN OLD LEGEND CURRENT IN THE VOLGA DISTRICT

'And in praying use not vain repetitions, as the Gentiles do: for they think that they shall be heard for their much speaking. Be not therefore like unto them: for your Father knoweth what things ye have need of, before ye ask Him.' —Matt. vi. 7, 8.A BISHOP was sailing from Archangel to the Solovétsk Monastery; and on the same vessel were a number of pilgrims on their way to visit the shrines at that place. The voyage was a smooth one. The wind favorable, and the weather fair. The pilgrims lay on deck, eating, or sat in groups talking to one another. The Bishop, too, came on deck, and as he was pacing up and down, he noticed a group of men standing near the prow and listening to a fisherman who was pointing to the sea and telling them something. The Bishop stopped, and looked in the direction in which the man was pointing. He could see nothing however, but the sea glistening in the sunshine. He drew nearer to listen, but when the man saw him, he took off his cap and was silent. The rest of the people also took off their caps, and bowed.

'Do not let me disturb you, friends,' said the Bishop. 'I came to hear what this good man was saying.'

'The fisherman was telling us about the hermits,' replied one, a tradesman, rather bolder than the rest.

'What hermits?' asked the Bishop, going to the side of the vessel and seating himself on a box. 'Tell me about them. I should like to hear. What were you pointing at?'

'Why, that little island you can just see over there,' answered the man, pointing to a spot ahead and a little to the right. 'That is the island where the hermits live for the salvation of their souls.'

'Where is the island?' asked the Bishop. 'I see nothing.'

'There, in the distance, if you will please look along my hand. Do you see that little cloud? Below it and a bit to the left, there is just a faint streak. That is the island.'

In different years Tolstoy’s study was in different rooms. But it looked almost the same. In his study there always was the black couch, on which Tolstoy was born, books and photographs of his family and friends, and the writing desk of Persian walnut. The drawers in the desk still contain Tolstoy’s personal possessions: pens bearing traces of ink, pencils, a pen-knife, paper knives and a set of instruments.The Bishop looked carefully, but his unaccustomed eyes could make out nothing but the water shimmering in the sun.

'I cannot see it,' he said. 'But who are the hermits that live there?'

'They are holy men,' answered the fisherman. 'I had long heard tell of them, but never chanced to see them myself till the year before last.'

And the fisherman related how once, when he was out fishing, he had been stranded at night upon that island, not knowing where he was. In the morning, as he wandered about the island, he came across an earth hut, and met an old man standing near it. Presently two others came out, and after having fed him, and dried his things, they helped him mend his boat.

'And what are they like?' asked the Bishop.

'One is a small man and his back is bent. He wears a priest's cassock and is very old; he must be more than a hundred, I should say. He is so old that the white of his beard is taking a greenish tinge, but he is always smiling, and his face is as bright as an angel's from heaven. The second is taller, but he also is very old. He wears tattered, peasant coat. His beard is broad, and of a yellowish grey color. He is a strong man. Before I had time to help him, he turned my boat over as if it were only a pail. He too, is kindly and cheerful. The third is tall, and has a beard as white as snow and reaching to his knees. He is stern, with over-hanging eyebrows; and he wears nothing but a mat tied round his waist.'

'And did they speak to you?' asked the Bishop.

'For the most part they did everything in silence and spoke but little even to one another. One of them would just give a glance, and the others would understand him. I asked the tallest whether they had lived there long. He frowned, and muttered something as if he were angry; but the oldest one took his hand and smiled, and then the tall one was quiet. The oldest one only said: "Have mercy upon us," and smiled.'

Leo and Sofia Tolstoy with eight of their 13 children, 1907While the fisherman was talking, the ship had drawn nearer to the island.

'There, now you can see it plainly, if your Grace will please to look,' said the tradesman, pointing with his hand.

The Bishop looked, and now he really saw a dark streak—which was the island. Having looked at it a while, he left the prow of the vessel, and going to the stern, asked the helmsman:

'What island is that?'

'That one,' replied the man, 'has no name. There are many such in this sea.'

'Is it true that there are hermits who live there for the salvation of their souls?'

'So it is said, your Grace, but I don't know if it's true. Fishermen say they have seen them; but of course they may only be spinning yarns.'

'I should like to land on the island and see these men,' said the Bishop. 'How could I manage it?'

'The ship cannot get close to the island,' replied the helmsman, 'but you might be rowed there in a boat. You had better speak to the captain.'

The captain was sent for and came.

'I should like to see these hermits,' said the Bishop. 'Could I not be rowed ashore?'

The captain tried to dissuade him.

'Of course it could be done,' said he, 'but we should lose much time. And if I might venture to say so to your Grace, the old men are not worth your pains. I have heard say that they are foolish old fellows, who understand nothing, and never speak a word, any more than the fish in the sea.'

'I wish to see them,' said the Bishop, 'and I will pay you for your trouble and loss of time. Please let me have a boat.'

Tolstoy with his wife Sofia in 1907, three years before his death. The author was 34 in 1862 when he married his 18-year-old bride Sofia Behrs, daughter of a Moscow doctor. Friends since childhood, Leo, known as Lyova, and Sofia were both impetuous, romantic, high-minded and passionate. Both also idealized family life, yet before they married she discovered that his youthful promiscuity had included a liaison with a peasant woman who still worked at the estate had given birth to his son. Sofia went on to bear her husband 13 children (five of whom died in childhood). She managed his estate and idolized him as a writer, copying his manuscripts and acting as his agent, reader and critic. In her diary, she wrote of the pleasure she took in copying her husband’s manuscripts: ‘Copying War and Peace and Lev Nikolayevitch’s works in general gave me a great aesthetic enjoyment. I used to wait for the evening undaunted by the task and delighted at the opportunity to renew the pleasure of following the further course of the action. I admired this life of the mind, all the twists and turns, the surprises and various incomprehensible forms of his writing.’There was no help for it; so the order was given. The sailors trimmed the sails, the steersman put up the helm, and the ship's course was set for the island. A chair was placed at the prow for the Bishop, and he sat there, looking ahead. The passengers all collected at the prow, and gazed at the island. Those who had the sharpest eyes could presently make out the rocks on it, and then a mud hut was seen. At last one man saw the hermits themselves. The captain brought a telescope and, after looking through it, handed it to the Bishop.

'It's right enough. There are three men standing on the shore. There, a little to the right of that big rock.'

The Bishop took the telescope, got it into position, and he saw the three men: a tall one, a shorter one, and one very small and bent, standing on the shore and holding each other by the hand.

The captain turned to the Bishop.

'The vessel can get no nearer in than this, your Grace. If you wish to go ashore, we must ask you to go in the boat, while we anchor here.'

The cable was quickly let out, the anchor cast, and the sails furled. There was a jerk, and the vessel shook. Then a boat having been lowered, the oarsmen jumped in, and the Bishop descended the ladder and took his seat. The men pulled at their oars, and the boat moved rapidly towards the island. When they came within a stone's throw they saw three old men: a tall one with only a mat tied round his waist: a shorter one in a tattered peasant coat, and a very old one bent with age and wearing an old cassock—all three standing hand in hand.

The oarsmen pulled in to the shore, and held on with the boathook while the Bishop got out.

The old men bowed to him, and he gave them his benediction, at which they bowed still lower. Then the Bishop began to speak to them.

'I have heard,' he said, 'that you, godly men, live here saving your own souls, and praying to our Lord Christ for your fellow men. I, an unworthy servant of Christ, am called, by God's mercy, to keep and teach His flock. I wished to see you, servants of God, and to do what I can to teach you, also.'

The old men looked at each other smiling, but remained silent.

'Tell me,' said the Bishop, 'what you are doing to save your souls, and how you serve God on this island.'

The second hermit sighed, and looked at the oldest, the very ancient one. The latter smiled, and said:

'We do not know how to serve God. We only serve and support ourselves, servant of God.'

'But how do you pray to God?' asked the Bishop.

'We pray in this way,' replied the hermit. 'Three are ye, three are we, have mercy upon us.'

And when the old man said this, all three raised their eyes to heaven, and repeated:

'Three are ye, three are we, have mercy upon us!'

The Bishop smiled. 'You have evidently heard something about the Holy Trinity,' said he. 'But you do not pray aright. You have won my affection, godly men. I see you wish to please the Lord, but you do not know how to serve Him. That is not the way to pray; but listen to me, and I will teach you. I will teach you, not a way of my own, but the way in which God in the Holy Scriptures has commanded all men to pray to Him.'

And the Bishop began explaining to the hermits how God had revealed Himself to men; telling them of God the Father, and God the Son, and God the Holy Ghost.

'God the Son came down on earth,' said he, 'to save men, and this is how He taught us all to pray. Listen and repeat after me: "Our Father."'

And the first old man repeated after him, 'Our Father,' and the second said, 'Our Father,' and the third said, 'Our Father.'

'Which art in heaven,' continued the Bishop.

The first hermit repeated, 'Which art in heaven,' but the second blundered over the words, and the tall hermit could not say them properly. His hair had grown over his mouth so that he could not speak plainly. The very old hermit, having no teeth, also mumbled indistinctly.

The Bishop repeated the words again, and the old men repeated them after him. The Bishop sat down on a stone, and the old men stood before him, watching his mouth, and repeating the words as he uttered them. And all day long the Bishop laboured, saying a word twenty, thirty, a hundred times over, and the old men repeated it after him. They blundered, and he corrected them, and made them begin again.

The Bishop did not leave off till he had taught them the whole of the Lord's prayer so that they could not only repeat it after him, but could say it by themselves. The middle one was the first to know it, and to repeat the whole of it alone. The Bishop made him say it again and again, and at last the others could say it too.

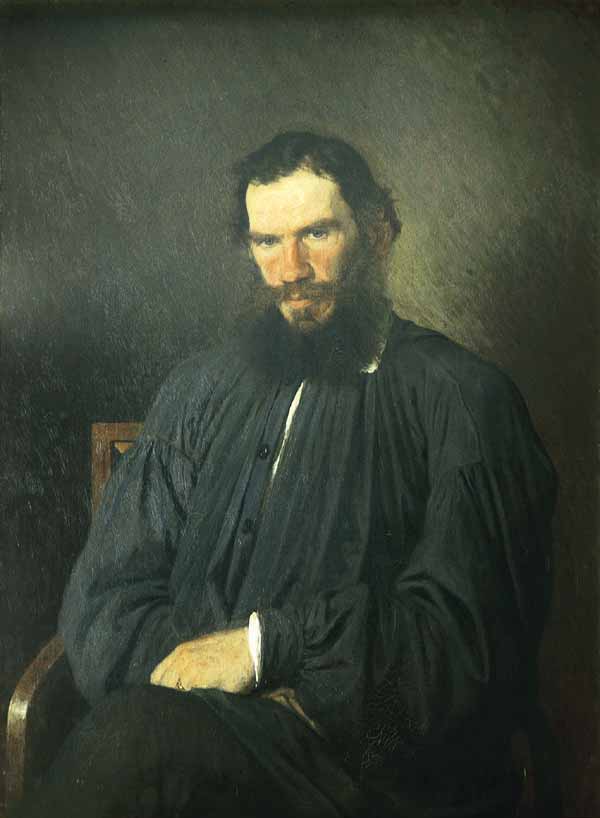

A portrait of Leo Tolstoy by Ivan Kramskoy, 1873. In her diary, Tolstoy’s wife Sofia recalled: ‘I remember going up to the small drawing room and looking at these two artists, one painting a portrait of Tolstoy and the other writing his novel Anna Karenina. Their expressions were serious and concentrated, two real artists of the first order, and I felt such a deep reverence for them in my heart.’It was getting dark, and the moon was appearing over the water, before the Bishop rose to return to the vessel. When he took leave of the old men, they all bowed down to the ground before him. He raised them, and kissed each of them, telling them to pray as he had taught them. Then he got into the boat and returned to the ship.

And as he sat in the boat and was rowed to the ship he could hear the three voices of the hermits loudly repeating the Lord's prayer. As the boat drew near the vessel their voices could no longer be heard, but they could still be seen in the moonlight, standing as he had left them on the shore, the shortest in the middle, the tallest on the right, the middle one on the left. As soon as the Bishop had reached the vessel and got on board, the anchor was weighed and the sails unfurled. The wind filled them, and the ship sailed away, and the Bishop took a seat in the stern and watched the island they had left. For a time he could still see the hermits, but presently they disappeared from sight, though the island was still visible. At last it too vanished, and only the sea was to be seen, rippling in the moonlight.

The pilgrims lay down to sleep, and all was quiet on deck. The Bishop did not wish to sleep, but sat alone at the stern, gazing at the sea where the island was no longer visible, and thinking of the good old men. He thought how pleased they had been to learn the Lord's prayer; and he thanked God for having sent him to teach and help such godly men.

So the Bishop sat, thinking, and gazing at the sea where the island had disappeared. And the moonlight flickered before his eyes, sparkling, now here, now there, upon the waves. Suddenly he saw something white and shining, on the bright path which the moon cast across the sea. Was it a seagull, or the little gleaming sail of some small boat? The Bishop fixed his eyes on it, wondering.

'It must be a boat sailing after us,' thought he 'but it is overtaking us very rapidly. It was far, far away a minute ago, but now it is much nearer. It cannot be a boat, for I can see no sail; but whatever it may be, it is following us, and catching us up.'

And he could not make out what it was. Not a boat, nor a bird, nor a fish! It was too large for a man, and besides a man could not be out there in the midst of the sea. The Bishop rose, and said to the helmsman:

'Look there, what is that, my friend? What is it?' the Bishop repeated, though he could now see plainly what it was—the three hermits running upon the water, all gleaming white, their grey beards shining, and approaching the ship as quickly as though it were not morning.The steersman looked and let go the helm in terror.

'Oh Lord! The hermits are running after us on the water as though it were dry land!'

The passengers hearing him, jumped up, and crowded to the stern. They saw the hermits coming along hand in hand, and the two outer ones beckoning the ship to stop. All three were gliding along upon the water without moving their feet. Before the ship could be stopped, the hermits had reached it, and raising their heads, all three as with one voice, began to say:

'We have forgotten your teaching, servant of God. As long as we kept repeating it we remembered, but when we stopped saying it for a time, a word dropped out, and now it has all gone to pieces. We can remember nothing of it. Teach us again.'

The Bishop crossed himself, and leaning over the ship's side, said: 'Your own prayer will reach the Lord, men of God. It is not for me to teach you. Pray for us sinners.

And the Bishop bowed low before the old men; and they turned and went back across the sea. And a light shone until daybreak on the spot where they were lost to sight.

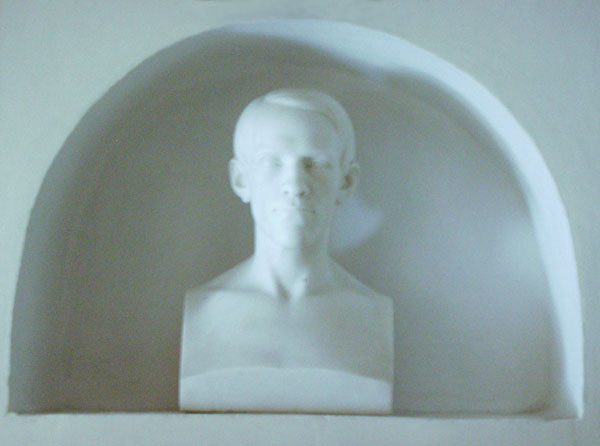

In a semi-circular niche in the wall of Tolstoy’s study, where he wrote Anna Karenina, sits a marble bust of the author’s beloved brother Nikolay. Tolstoy had it made after his brother’s death. (Nikolay died of consumption at the age of 37). It was a great loss for young Tolstoy. In his diary he wrote: “He was one of the best people I have ever known, he was my brother, all my best memories are connected with him; and he was my very best friend.” Many years later Tolstoy recalled how Nikolay, at age 12, had told his family about a great secret. If it could be revealed, no one would ever die; there would be no wars or sufferings. And he added that he had written the secret on a little green stick and buried it on the edge of the ravine at the family estate, Yasnaya Polyana. As a boy Tolstoy believed it was true, and tried to find the magic stick. In his old age Tolstoy wrote: “It was so very good. And I thank God that I could play such games. We called it a game, though anything in the world can be a game except that." In his own novels and stories, articles and philosophical works Leo Tolstoy would ponder over the same idea—of love understanding and common good. Tolstoy mentioned the story about the little green stick in the first version of his will; he asked his family to bury his body without any ceremonies in a simple wooden coffin at the place of the little green stick. On the day of his burial the coffin with Tolstoy’s body was put in front of the bust of his brother. Some six thousand people came here on that day. At three o’clock Tolstoy’s body was committed to the earth at the very place where, according to the legend, the little green stick was buried. There were no religious ceremonies; the mourners simply knelt down around the grave.

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024