Theodore Sorensen (May 8, 1928-October 31, 2010): ‘I think words matter a great deal.’[Ed. note: Theodore "Ted" Sorsenson—presidential advisor, lawyer, writer, special counsel and adviser to President John F. Kennedy who called him his "intellectual blood bank," died on October 30 following a stroke. During his years in the White House, Sorensen was not only a witness to history, his speeches helped shape it, as did his counsel during the Cuban missile crisis, when he helped tailor the President's correspondence with Russian premier Nikita Khrushchev and worked on Kennedy's initial address to the nation about the crisis, Remembering the President's assassination as "the most deeply traumatic experience of my life," he said he "never considered a future without him." Although he submitted his resignation to President Lyndon B. Johnson the day after the assassination, he was persuaded to remain on staff through the transition. He then drafted LBJ's first Congressional address as well as his 1964 State of the Union speech. He became the first of JFK's inner circle to leave the new administration upon his resignation on February 29, 1964. Even after returning to the law with the firm of Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison LLP, Sorensen remained active in politics, joining Robert F. Kennedy's 1968 presidential campaign as an adviser. During the last four decades of his life, Sorensen served as an adviser to governments around the world and to major international corporations. A supporter of Barack Obama, Sorensen was reported to have assisted in writing of the President's Inaugural Address.

On February 25, 2010, he was awarded the National Humanities Medal for 2009 in a ceremony in the East Room of the White House. He was cited for "Advancing our understanding of modern American politics. As a speechwriter and advisor to President Kennedy, he helped craft messages and policies, and later gave us a window into the people and events that made history."

Theodore Sorensen was married to Gillian Sorensen, who survives him, along with three sons—Eric, Stephen and Philips—and a daughter, Juliet Sorensen.

A wise and generous man, Theodore Sorensen treasured the power of words to make a difference in peoples' lives and to change the course of history. A civil tongue in an uncivil era, his graciousness was as impressive as his mind. In this issue we honor Sorensen's achievements in three parts: first, a poignant, insightful tribute penned by Ed Vilade in The Guardian; a fascinating 2008 interview with Jane Greer of the Unitarian Church website uuworld.org centered on the role his Unitarian faith played in Sorensen's political life, especially during the Kennedy year; and an undated (but clearly recent) interview with George Washington University focusing specifically on the inside details of the Cuban missile crisis, JFK's finest hour.]

***

Leave your ego at the White House door, speechwriters—The late Ted Sorensen needed much more than a mastery of rhetoric to be JFK's great counselor

By Ed ViladeThe death of Ted Sorensen provides us with a melancholy, yet valuable, occasion to appraise and appreciate the qualities of intellect and character that made him John F Kennedy's indispensable man, and the speechwriter's patron saint.

Sorensen bridled at being called a speechwriter. He once said that his New York Times obituary would be headlined "Theodore Sorenson, Kennedy Speechwriter,” getting both his surname and his occupation wrong.Indeed, he held a law degree and carried the amorphous title of counselor to Kennedy (he titled his autobiography Counselor). He emphasized that rejecting the designation of speechwriter for his epitaph was not derogating the craft. On the contrary, he took pride in his contributions to Kennedy's speeches. He simply, and rightly, believed that he brought more to the relationship with Kennedy than rhetoric. His quiet Midwestern demeanor belied a formidable and restless intellect that constantly engaged and challenged Kennedy. He consistently told fellow speechwriters that they owed their speakers more than words—nothing less than complete intellectual engagement and the contribution of ideas. Good speechwriters listened and many have benefited from his advice.

Sorensen brought much more than intellectual heft—or rather, less. He has frequently been called Kennedy's "alter ego.” However, to be such, one must possess an ego. Sorensen showed none. He totally sublimated his own personality and interests. That is precisely what a good speechwriter should do.

No less an intellect—and old adversary—than Richard Nixon spoke admiringly of Sorensen as having a mind "that's clicking and clicking all the time.”

He added: "Sorensen ... is tough, cold, not carried away by emotion; and he has the rare gift of being an intellectual who can completely sublimate his style to another individual ... "

Theodore Sorensen on JFK and the Call to Service, December 20, 2007Only through such sublimation can the speechwriter truly find the speaker's voice. The words belong to the one who speaks them, and must sound like that person. A speechwriter is, in a way, like a playwright crafting a soliloquy—the character in all particulars must be foremost in the writer's mind. A speechwriter who loves his or her own style and words will not enjoy a lengthy career at the White House.

Sorensen quietly deplored the trend towards presidential speechwriters coming out of the shadows to take credit for memorable phrases, such as the George W. Bush speechwriter who claimed credit for "axis of evil.” He would have been happy to have foregone all acknowledgment, but his talents called attention to themselves.

The urge by speechwriters to claim credit may be deplorable, but it is understandable in the White House milieu. Egos tower all around, and the isolation verges on the bizarre. The quotidian descriptors "pressure cooker,” "meat-grinder" and "eye of the hurricane" do not do justice to the atmosphere, either at the White House or in a major political campaign. All the mechanisms designed to limit access to the president and his staff serve to cut them off from normal life. The recent ordeal of the Chilean miners—whose every scintilla of communication, food, water and even oxygen came through a slender tube—perhaps provides a more apt analogy.

It takes extraordinary equilibrium, self-possession and sense of purpose to withstand the pressures and produce words that resonate with people who are outside the barricades. The best do that, and Sorensen was one of the best.

Those pressures can be killing. Samuel Johnson once said: "When a man knows he is to be hanged in a fortnight, it concentrates his mind wonderfully." A speechwriting deadline is like an execution date—from the moment of getting the assignment, it looms like a gallows. And campaign and White House deadlines come thick and fast. One either concentrates, or flees.

Never was that pressure greater than in 1961 during the Cuban missile crisis, when Sorensen was charged with drafting letters to the Soviet leader Nikita Khruschev, negotiating a diplomatic solution to a potentially world-ending confrontation. Anything he wrote to offend the Soviets could have precipitated the ultimate cataclysm. Apparently, he chose the right words.

As he did on so many other occasions. There is no real trick to producing memorable phrases—any competent speechwriter knows the rhetorical techniques. For example, "Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country" is an example of a rhetorical technique Sorensen, and others, have called "the reversible raincoat.” Another "reversible" Kennedy quote is, "Let us never negotiate out of fear, but let us never fear to negotiate.” Sorensen used a number of similar devices to create memorable phrases, but he could call on such a vast store of historical, political, social, economic and other material that he had enormously more grist to produce his memorable lines than most who have ever plied the craft.

As Sorensen said in his autobiography: "The right speech on the right topic delivered by the right speaker in the right way at the right moment ... can ignite a fire, change men's minds, open their eyes, alter their votes, bring hope to their lives, and, in all these ways, change the world. I know. I saw it happen."

No, Ted, you helped it happen—as well as anyone ever has.

From guardian.co.uk, Thursday 4 November 2010.

***

JFK's Unitarian Speechwriter

In Kennedy's inaugural address, he concludes saying, "With history the final judge of our deeds . . ." That's not what other churches would say. That's Unitarianism.

By Jane GreerIn his memoir, Counselor: A Life At The Edge Of History (HarperLuxe, 2008) Ted Sorensen, President John F. Kennedy's closest advisor and major speechwriter, celebrates his Unitarian upbringing in 1930s Nebraska. "Like the Good Samaritan, of whom Jesus spoke," Sorensen writes in a chapter about his religious and political development as a young person, "Unitarians have a love for the least, the last, and the lost, a belief in integrating faith with works."

Sorensen, who was born in 1928 in Lincoln, Nebraska, was one of five children. His father, C.A. Sorensen, was a well-known progressive politician and lawyer who served four years as Nebraska's attorney general. As a student at Grand Island Baptist College C.A., a talented debater and orator, competed in the Nebraska State Oratory Contest with an address entitled "The Dead Hand of the Past," in which he impugned the importance of religion. The speech won him first prize and expulsion from college. C.A.'s story made the news, and he was soon after contacted by Walter Locke, associate editor of the Nebraska State Journal, who told him that he needed to be at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln, and, also, that he needed to go to a Unitarian church. Locke helped with his university admission, and the Lincoln Unitarian minister arranged for a scholarship covering his tuition. So began the Sorensen family's relationship with Unitarianism.

Unitarian values, Sorensen writes in Counselor: A Life at the Edge of History, are reflected in many of the speeches he drafted for Kennedy. Sorensen worked with Kennedy from his start as a senator in 1953 through his assassination as president in November 1963. A graduate of the University of Nebraska law school, Sorensen was only 25 when he started with Kennedy. However, even as a young man, he had already asserted himself as a civil rights activist, conscientious objector, and liberal.

Ted Sorensen on JFK, Mitt Romney and religion—how two politicians approached a touchy subject: ‘Romney wanted religion to play a major part in public policy making; Kennedy did not want that at all. Not only his speech but his Presidency demonstrated that was his conviction.’ December 20, 2007Religion was an especially important issue in the 1960 presidential race, when many Protestants viewed Kennedy's Catholicism as a detriment, fearing that the pope and the Catholic hierarchy would unduly influence him. In probably his best-known speech on the subject, delivered to the Houston Ministerial Association on September 12, 1960, Kennedy asserted, "I believe in an America where the separation of church and state is absolute—where no Catholic prelate would tell the President (should he be Catholic) how to act, and no Protestant minister would tell his parishioners for whom to vote. . . ."

After his White House years, Sorensen worked as a private attorney in the field of international law. In 1966, he joined the firm Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison, where he specialized in representing clients on relations with foreign governments, a task that took him all over the world. As part of these assignments he had the opportunity to meet with world leaders ranging from Nelson Mandela to Manuel Noriega. Sorensen suffered a stroke in 2001, which left him visually impaired. With time on his hands, he was finally able to turn to writing his memoir, which he did with the help of Adam Frankel, a Princeton University and London School of Economics graduate. The book took six years to complete.

Sorensen spoke with UU World at his apartment overlooking Central Park in New York City in September 2008. His sister, Ruth Sorensen Singer, was visiting and offered an anecdote from her childhood, which is included in the interview.

How did people feel about Roman Catholics in the 1950s and '60s?

Clearly there was a very large number that didn't think Catholics should be president of the U.S. There was an organization in which Unitarians, along with Southern Baptists, probably played an important role. It was called POAU, Protestants and Other Americans United for the Separation of Church and State [now known as Americans United for Separation of Church and State]. I think that a Methodist bishop [Garfield Bromley Oxnam] may have been the president at that time, and I had a secret meeting with him to enlist his help with the campaign.

To support Kennedy?

To at least support a statement by a lot of leading Protestant clergymen saying that religion should not play a role in the selection of a president. They were not thereby committing themselves to campaign for Kennedy, but it's a little like when I mobilized the South Africa Free Elections Fund foundation many years later. The reason it was a foundation and contributions were tax-deductible was because it was for voter education in South Africa. Mandela was smart enough to realize immediately that the whites didn't need voter education; they'd been voting all their lives. So a statement saying religion should not play any role in the selection of a president could only benefit one person.

How did religion feature as a campaign issue?

Clearly, whether we liked it or not, Kennedy's religion was a major issue. A group of leading Protestant clergymen had a conference at the Waldorf Astoria, which they called the Conference on Religious Freedom, which was to discuss the presidential election, because they thought religious freedom was at stake if a Roman Catholic became president. In fact, the Rev. Norman Vincent Peale, author of The Power of Positive Thinking, did not have such positive thoughts about Kennedy and said something like, "I'm not saying that we should be opposed to his election, I'm just saying it would be a different country if he were elected." To which Kennedy said, "He could have been complimenting me."

Richard Nixon, Kennedy's opponent, piously said, "I am not going to raise the religion issue." To demonstrate his sincerity, he said that in every state. So, of course it was out there. We would see hate mail coming into the office; we would see people holding up anti-Catholic signs on the campaign trail, along the routes of the motorcade. Finally, in what I have to assume was an annual meeting, the Houston Protestant ministers invited Kennedy and Nixon to come speak to them. Nixon shrewdly declined, saying he was busy. I remember the discussion, which Robert Kennedy, who was [his brother's] campaign manager, joined. We decided that we had no wish to avoid [the issue], bury it, or ignore it. We needed to take this on.

The President of the American Unitarian Association issued a statement on Kennedy's death on how much he had meant to freedom of religion and free speech in this country. That was an extraordinary thing for a Unitarian to say about a Catholic politician. Kennedy was clearly more than a Catholic politician.

What are some of the Unitarian principles in Kennedy's speeches?

My favorite of all of Kennedy's speeches—and usually I try to minimize my role, but in this I did have a major role—was his commencement address at American University [in 1963]. In that speech, one of the lines is, "Our problems are man-made—therefore they can be solved by man." Sounds like good Unitarianism to me. In the inaugural address, he concludes saying, "With history the final judge of our deeds . . ." That's not what other churches would say. That's Unitarianism.

Did your family go to church?

My father had been a Unitarian ever since his change of fortune that I describe in the book. My mother was born and raised Jewish, even though, for one reason or another, she was no longer an observant Jew. She went to church most of the time, probably not as regularly as my father. All five children went to church. After I was too old to go to Sunday school, I went to church.

Did the minister talk about God?

No.

Was he more of a humanist?

Very much so.

Why do you not refer to yourself as a Unitarian Universalist?

I grew up a Unitarian, and I still am a Unitarian. I'm sure Universalists are equally wonderful.

Why are you not a current member of a church?

Before I lost effective use of my eyes, every Sunday morning I would play tennis. And I justify this when people ask me by saying, "It's OK because tennis goes back to the Bible." When they challenge that, I say, "Of course. There's a passage in the Bible: 'Joseph served in Pharaoh's court.'"

I thought that it was one of the basic tenets of Unitarianism that "the whole world is my church." Look at the view out this window. What church could possibly be as beautiful as that? [Ruth Sorensen Singer:] We didn't have church over the summer because it was a small church, and the minister got time off. But when I was around 10 years old, someone asked me, "How come you don't go to church in the summer?" And I said, "The minister needs time off." And they asked, "Don't you need God during the summer?" And I said, "I guess we don't need God in the winter, either."

Did you ever have any problems as a Unitarian working with a Roman Catholic?

No problem whatsoever. Fortunately, he did not go along with the Catholic hierarchy's position on church and state. He was opposed to federal funds for parochial schools. In those days, abortion was not a big issue. It was the days before Roe v. Wade. There was no big political debate about abortion. There was a modest debate about population control. And he was the first president of the U.S. to support U.N. funding for population control.

It sounds like Kennedy had character.

Yes, he did. And in many, broader senses of the word, he was a humanist because he looked to human beings to solve problems caused by human beings.

Are you concerned about the weakening of the divide between church and state?

I'm very worried about it. And I strongly disagree with it. It's so ironic that the religious right in those days opposed Kennedy because they said if a Catholic is elected president then members of the clergy might influence public policy. And a priest or a clergyman might even tell his parishioners how to vote, which is all going on now. From the very same quarters that were attacking Kennedy—from the religious right.

You support [Democratic presidential nominee Sen. Barack] Obama?

Very much so.

You have said that you see parallels between his being black and Kennedy's Catholicism.

I certainly do. We'll find out if being black is even a bigger obstacle than being Catholic. It might be bigger; people don't admit to their prejudices and bigotry.

Is eloquence still appreciated?

I hope so. It's words that enable a president of the U.S. to galvanize support in the country, to mobilize support in the Congress, and to attract support from our allies and others around the world. Kennedy was respected and indeed revered in many countries of the world because you could tell from his words, his statements, his speeches, his positions, that he was a man with a good heart and compassion, and wanted peace. Yes, I think words matter a great deal.

Is it too late for a Kennedy to galvanize the country?

I don't know why it should be. It requires remarkable leadership. Attitudes in this country are largely set at the top. Now we have a president who, with his cronies, has dumbed down governing and speeches, and it's not surprising that for some time the public has not had someone who could elevate their sights. That's what Kennedy did: He lifted up the sights of the American people. He didn't speak down to them. Another chap might do it again. I think Obama might just be that kind of president.

Kennedy seemed to have a special appeal to youth.

Nobody that young had ever run for president before. He appealed to the young. In part because his ideas were fresh and new, offering change and hope. And Bobby Kennedy likewise. I think it was the combination of those two deaths and Dr. [Martin Luther] King [Jr.]'s death that added to the disillusionment of young people along with Nixon, Vietnam, and Watergate. They became cynical, and no candidate had any particular appeal to them. Obama is bringing them back in, and I think that's very important and healthy for the country. Most of the activism is going to come from young people.

What do you think of churches supplying more and more social services?

It's fine as long as it's not with federal or other public taxpayers' funds. Because it's impossible for those churches to do it in a way that does not proselytize for new members in their churches, and taxpayer funds should not be used for that purpose. In terms of churches opening shelters and kitchens for the poor and things like that, good! When I was a young man working for civil rights, I looked to churches for a lot of the help I got in those days when civil rights was not a popular issue.

Kennedy seemed to favor a strong role for the executive branch.

He was in favor of a president who leads. He recognized that presidents could make it a better world and a better country. He felt it was their obligation to do that, and if that encourages presidents who are less competent and more right wing in their ideology to also be strong presidents and lead us in the wrong direction citing Kennedy, then yes, I do worry about that. I was worried when [George W.] Bush and Condoleezza Rice invoked Kennedy and the Cuban Missile Crisis when they favored a unilateral invasion of Iraq, which was the last thing in the world Kennedy would have done.

Was Kennedy against war?

He had served in the war and had seen his brother and two of his best friends killed in the war. Although he was elected in part because he was a war hero, he was very antiwar. He was the commander in chief of the greatest military force in the world, maybe in the history of the entire world, and as Bush and even Clinton discovered, it's so tempting to say, "I've got all this military power; of course, I'll use it." Kennedy never invaded anybody.

What advantages has Unitarianism given you?

Unitarians know how to be skeptical; they're skeptics by nature. Unitarians know how to ask questions-hard, tough questions-and that's very important in a complicated world in which we now live.

And yet, in the book you describe yourself as an optimist.

I don't see any inconsistency between skepticism and optimism. You'll have a hard time knocking either one of them out of me.

What does freedom of religion mean to you?

Freedom of religion in this country is freedom to go to the church of your choice but also go to no church at all. I don't mind when children are asked to recite the Lord's Prayer at school. As my sister said, she could never keep it straight whether she was apologizing for her sins or her trespasses. Therefore I don't mind that the U.S. Senate opens with a prayer and things of that sort. There are some people who think that separation of church and state means being anti-religious. I'm not anti-religious. If we're all going to get along in one country, even Unitarians have to be reasonable.

Theodore Sorensen’s Counselor: A Life At The Edge Of History is available at www.amazon.com

***

On The Cuban Missile Crisis

‘It was the only time during my three years in the White House that I would wake up in the middle of the night agonizing over what was the right approach, what would work, what would not blow up the world.’

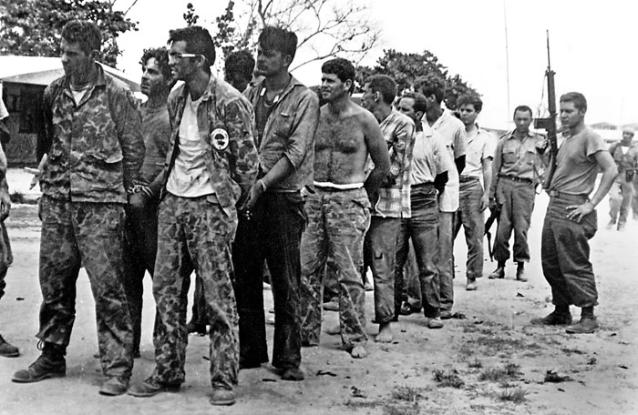

Theodore Sorensen discusses the Cuban Missile Crisis, and his role in the White House during those 13 days, at The Levin InstituteCan I ask you, first of all... if we start in 1961—President Kennedy was just coming to power, he had a new administration—how do you think he got embroiled in the Bay of Pigs, and why?

1961 was in many ways the height of the Cold War. Shortly before President Kennedy took office, Khrushchev made statements about "We will bury you," statements about wars of liberation all over the world. The Soviet Union, in contrast with what we see in Moscow today, was a powerful country, militarily powerful, technologically, scientifically, even economically powerful, with steel and other major industries that were surpassing the United States and pointing to the Third World as a way for all the rest of the world to go, not the way of democracy. So President Kennedy had reason to be concerned about a Soviet outpost in Cuba, 90 miles from our shore. In addition to that, Cuba was a gnawing, nagging political problem, almost an emotional problem. Castro seemed like this taunting figure that got into the skin of Americans.

And was Kennedy being informed, was he being given enough information by the various agencies, to make strong decisions about what the next move should be?

Kennedy had been briefed on the Bay of Pigs invasion plan by President Eisenhower and his outgoing team, and felt that a plan that he had inherited, in which a band of Cuban exiles were to liberate their own country, was one he could hardly turn his back on. It was a decision that he came to regret, but at the time it seemed, if this is what they wanted to do, surely the United States should help get rid of a communist dictatorship in our hemisphere. The fact is that the CIA, the Central Intelligence Agency, which had devised the plan, sold it to the President on the basis of a number of premises which turned out not to be correct.

Was there any sense at the time that Kennedy was... trapped is too strong a word, but put into a position through his election campaign, where he campaigned quite strongly that the Eisenhower regime had not done anything about Castro, that Kennedy was almost forced into making a move on Castro?

I don't believe that he was forced to do so. I'm not so certain that anything he said in the campaign, despite one rather broad statement about action to get rid of communism in Cuba, committed him to the Bay of Pigs plan. No, I think that the decision was made all over again to proceed with what had been recommended to him by a mostly inherited team, people wearing all kinds of medals and people with dark glasses and murky backgrounds, for whom at the time he had a great respect.

Once word came through that the invasion had failed, that the troops had either been killed or captured, what was the reaction within the White House?

Jack Kennedy was devastated by the fiasco at the Bay of Pigs, and he said it was a fiasco. He was not accustomed to failure in politics or in life. He felt personally responsible for the brave Cuban exiles who had been placed on that island by United States ships and under United States sponsorship; and he was also angry, angry at himself for having paid attention to the experts without checking out their premises more carefully, angry at the Central Intelligence Agency for having sold him a bill of goods about a plan that supposedly would not have any discernible American connection and that had all these safety fall-backs, a plan that they told him would lead to an uprising of the Cuban people—all of which turned out to be nonsense; and disappointed in his own military leaders and others, that they had not asked tougher questions and checked out the plan more carefully.

Sorensen on JFK’s reaction to the Bay of Pigs debacle: ‘Jack Kennedy was devastated by the fiasco at the Bay of Pigs, and he said it was a fiasco. He was not accustomed to failure in politics or in life. He felt personally responsible for the brave Cuban exiles who had been placed on that island by United States ships and under United States sponsorship; and he was also angry, angry at himself for having paid attention to the experts without checking out their premises more carefully…’Did this, in the coming crisis that was about to happen, alter Kennedy's attitude towards people like the Joint Chiefs and the CIA?

It altered his whole approach toward government. He realized that intelligence officers and military officers were human beings, capable of imperfection, as he was. He realized that he needed people who thought the way he thought and looked at the world the way he looked at it, to join him in these sessions, and asked Robert Kennedy, his brother, the Attorney General, and me to sit in on National Security Council meetings from then on. He decided to make some changes in personnel in all of the agencies that were involved; he decided to make some changes in policy as to how we would isolate Cuba, some changes in procedure, all of which stood him in very good stead when we had another crisis in Cuba a year and a half later.

What were the consequences of the Bay of Pigs on the Kennedy Administration?

There were some favorable consequences, in the sense that he made the changes I mentioned in policy, procedure, personnel; he realized that primarily political questions cannot be solved by military means alone, which caused him to take a very different look at Indo-China and Vietnam and ask much tougher questions of the military; and told me some months afterwards that had it not been for the stumbling at the Bay of Pigs, we probably would have been knee-deep in Indo-China by that time. Interestingly enough, it did not hurt him much politically. Although it caused the President himself to realize that he didn't have a magic touch, there wasn't going to be automatic victories every time he put his hand to something, and he felt flawed, the American people were absolutely astounded by his willingness to take responsibility for the Bay of Pigs. Here was a plan that he had inherited—he could have blamed it on his predecessor, he could have blamed it on the hold over officers in the CIA and in the Pentagon, but instead he stood up at a press conference and said, "This is my responsibility: I'm the officer in charge, and we're going to investigate and find out what went wrong, and make sure it doesn't happen again." And as a result, his standing in the popularity polls went up, which caused him some wry amusement.

I believe in your book you mention the fact that he couldn't believe he'd been so stupid to have let others influence him that way. Do you remember him saying that?

I remember this very well. It was the day that the invasion and the aftermath ended. We were in his office, and he went outside to walk in the sunshine in the April day; we walked around the garden in the back, and he was more distraught than I'd ever seen him. "How could I have been so stupid?" he said. "How could I have let the experts so mislead me? I never pay attention... I never rely on experts alone." That's how he'd gotten where he was in politics, that's how he had achieved what he had achieved in life, by not relying on experts; and this time he had relied on them and they had let him down.

So, if I can take us forward now slightly. In the following year, in the summer of that year, the Russians started introducing a lot of ships, a lot of troops were going into...

No, a year later.

A year later—yes, sorry, 1962.

Yes, this was all '61...

'61, of course, yeah. And in the summer of '62, the first ships started arriving, a lot of activity was going on, and it led to the President making a speech, I think on the 13th of September, where he said the equipment they'd detected in Cuba was defensive, and he warned quite strongly the world that any offensive weapons would be dealt with. Do you remember that speech and what led to him making that speech?

There was a good deal of agitation in the Congress about the Soviet military activity in Cuba during the summer and early fall of 1962. Cuban refugees, most of whom could not tell the difference—nor could I—upon eye view, oa surface-to-air missile or an intercontinental ballistic missile, or a tactical weapon from a strategic weapon, were telling Senator Keating and other Republicans that the Soviets were putting long-range missiles, offensive strategic weapons, in Cuba, and there were demands for an investigation and calls for U.S. military action and so forth. The President felt he needed to say something. It was not a speech, but a press conference statement, in which he declared that to the best of our knowledge, and checking all of our intelligence sources, the weapons in Cuba were defensive weapons, which was their right under international law; but were it to be otherwise, the gravest consequences would ensue.

So, within a few weeks of that press conference, missiles were detected in Cuba. Can you tell me how you personally heard about it, and what your reaction was?

I believe it was Tuesday morning, October 16th—perhaps Monday, but I believe Tuesday... On Tuesday morning, October 16th, the President called me into his office and said that we had sent a U-2 surveillance flight over Cuba. The photo-intelligence had been interpreted, and the conclusion was that the Soviets were building offensive missile bases in Cuba. It was clearly a threat, it was clearly an action that required a response, and he was calling together the key people in his administration, the small group that would later be known as the Executive Committee of the Security Council, or Excom. He wanted me to attend those meetings, and he wanted me to bring to the first meeting copies of whatever statements he had made about the U.S. reaction to offensive weapons in Cuba.

What was that first meeting like, the first meeting of what was to become Excom?

The first meeting was very somber. Seated around the table were about a dozen of the President's closest and most trusted advisers, assembled not necessarily on the basis of position or even rank—because the Secretary of Treasury was there, for example; I had no military responsibilities; the Attorney General had no official national security responsibilities—but they were the people whose judgment he wanted on this matter. And we didn't spend a great deal of time wondering why the Soviets were doing this, because why they had done it, for whatever reason they had done it, they had done it in a surreptitious way, lying to the United States through a variety of messages and messengers, that they were only putting defensive weapons into Cuba, and those weapons constituted a clear and present danger to our security. Those missiles were capable of reaching almost every part of the United States and almost every part of Latin America. And so, after a briefing via the photo-intelligence people, the primary question was: what are our options? And although the option of doing nothing was always there, and from time to time would be mentioned by a variety of people around that table—"Get used to it. The Europeans are used to living on the bull's eye of nuclear weapons. Maybe the Americans had better get used to it also"—that was never an acceptable option to the President. We talked instead about the possibility of an air strike, which was at one time or another almost everybody's first choice, upon first thought, to knock out the missiles. We talked about an invasion of Cuba, which was always the preferred choice of the right wing, go in and take Cuba away from Castro and rid the island of communism, while at the same time getting rid of these missiles; a diplomatic approach, either bilaterally or through the United Nations: a blockade, or a quarantine, as it later came to be called. There were a number of permutations and combinations of all of these. No decision was made at that first meeting. But if a vote had been taken there—and fortunately it was not; it was not President Kennedy's method to take votes—an air strike was probably number one on everybody's list.

Is that what the recommendation was from the Joint Chiefs of Staff?

I think it was too early for the President to ask for a hard and fast recommendation. Clearly we needed more facts, we needed more exploration of what it was they were up to; we wanted to find out if at the same time there was any unusual activity around Berlin, because we thought Berlin, being the most vulnerable spot in the free world, and the most important, that this may be a one-two punch to suck us into concentrating on problems in Cuba and then act against Berlin or make some trade-off of the freedom of West Berlin for missiles in Cuba. So, without that kind of information, the President was not yet ready for hard and fast recommendations.

So what was to happen over the next few days, and what did the President do?

Those few days are something of a jumble in my memory, because we met constantly; information, new information, kept flowing in from the surveillance planes, both at high level and at, later on, low level. Once the Russians and Cubans knew that we knew, we put in low-level surveillance planes ... while we agonized over what is the right approach, what will solve the problem, what is an answer that is consistent with America's democratic values and its peaceful intentions toward the world as a whole, what kind of action can we take that will not precipitate World War III?

And was the President present at these meetings?

The President emphasized that all of us in the room should give top priority to this and try to get other problems postponed that may be on our desks, but at the same time that it was important not to let on to the Soviet Union that we knew what they were up to. That would give us some time to think and to plan and to react; and therefore we should not be breaking a lot of appointments, we should not have a mass of black official limousines parked outside the White House at strange hours of the day and night. And the President decided that he would maintain his own schedule of the appointments that he had with visiting heads of state, for example, and a campaign swing that he had already scheduled for the very next day. When he came back from that campaign swing, I said to him—and I can't remember now whether it was a memorandum or orally—that I'd noticed subordinates spoke far more frankly in front of their superiors: shall we say an Under Secretary of State or an Assistant Secretary of State in the presence of the Secretary of State, if the President was not in the room, and these were the people we needed to hear from, and we needed to hear from them frankly, and there was some value in his absenting himself from time to time. So thereafter he did absent himself from time to time, while always, at the end of the day, getting a report on how was our thinking progressing, what kinds of solutions were we formulating.

When JFK was being pressed to authorize an air strike on Cuba, his brother Robert (shown here with Theodore Sorensen) objected, saying ‘it would be regarded by the world as comparable to the bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese in 1941…’His brother Robert was present for most of the meetings, and I believe at one point he was reported to have said that he didn't wish his brother to become another Tojo. Do you remember that...?

I remember that very clearly. The air strike, as I mentioned, was a solution that people, from the most peace-minded to the most bellicose, thought from time to time might be the answer. An air strike, of necessity, had to be by surprise, it had to be without warning. In this case, it would have been an air strike against a small island which was inhabited by people of a different color, and Robert Kennedy—rightfully, in my opinion—drew the analogy that it would be regarded by the world as a bombing of Cuba, of bases in Cuba, comparable to the bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese in 1941. And he said, "I don't think I want my brother to become another Tojo." Some people scoffed at the analogy, but ultimately we drew back from the air strike alternative.

Could you tell me a little bit about how the decision to produce a quarantine or blockade came about? And also, what would be fascinating for me is the way that opinions were never locked in within Ex- people in fact changed their mind, and quite willingly so.

People changed their minds because there were no good solutions: every solution was full of holes and risks. It was the only time during my three years in the White House that I would wake up in the middle of the night agonizing over what was the right approach, what would work, what would not blow up the world. I remember very clearly when we brought in former Secretary of State Dean Acheson to talk to our group, expert on the Russians, expert on the Cold War, and he recommended the air strike. And someone said, "Mr. Secretary, if we bomb these Soviet missiles in Cuba, what will their reaction be?" And he said, "I know the Soviets very well," he said, "they will feel compelled to bomb NATO missile bases in Turkey." And somebody else said, "And then what would we do?" "Oh," he said, "under our NATO covenants, we would obligated to bomb Soviet missile bases inside the Soviet Union." "Oh, and then what will the Soviets do?" "Well," he said, "by that time we hope cooler heads will prevail and people will talk." There was a real chill in that room. In fact, if I may just take things out of sequence for a moment to tell you a true story. On the day that the missiles were withdrawn peacefully, Mr. Acheson wrote a wonderful hand-written to President Kennedy, congratulating him on his superb handling of the crisis; but some years later, felt compelled to write in a book or article that the Kennedys had just been lucky in the handling of the Cuban missile crisis. And so I was asked by the President about it, and I said, "He's right: we were lucky; we were lucky we didn't take his advice."

Now actually, I strayed from your question. But I tell that to indicate why the air strike, which sounded ideal, was scratched from the list of many minds, but not all. Many said, "Well, if we could just have a surgical air strike: the planes swoop in, dock out the missiles and fly off, and we're right back to the status quo and to where we were last summer." The Air Force, of course, admitted, "There's no such thing as a surgical air strike. To take those missiles safely, you have to take out the surface-to-air missiles, the anti-aircraft missiles, you have to take out any airplanes that are there, including Castro's small air force, as well as any Soviet planes that are there. You bomb the air bases - soon you're going to be bombing army bases as well, and chaos ensues, and an invasion is almost necessary," and so on and so forth. The diplomatic approach, which everybody said, "Well, that's certainly what we have to try first"—again the Pearl Harbor analogy and so forth—and I was given the assignment of trying to write a diplomatic note and draw up the scenario under which it could be handed to Khrushchev by some special emissary, and it would be so powerfully and logically and tightly written that he couldn't push a button or he couldn't send a note out and say "Go ahead and use those missiles" and at the same time not have an ultimatum that would cause history to blame the United States for a third world war, a nuclear holocaust, if Khrushchev did not bend to an ultimatum—and nobody thought he was the type who bended to an ultimatum. And I came back and reported I had tried, and although I had some confidence in my writing skills, I couldn't write such a diplomatic note. And so we began to divide basically into two camps: the air strike camp, or air strike-cum-invasion camp, and the naval quarantine or blockade camp. And then I was asked to write a... because time was getting short; we didn't know how much longer we had before the missiles were operational and whatever plan the Soviets had in mind might commence, or how much time we had before the Soviets discovered that we knew about it and that might precipitate action on their part. So I was asked to draft both speeches, both the speech for an air strike, because the President would certainly announce it to the world and the nation about the time the planes took off, and the speech for the blockade. And I came back again and said, "Well, now, the blockade speech - how do we explain this, and what's the blockade got to do with the missiles, and how's the blockade going to help?" And by getting answers to those questions, it not only strengthened my ability to write the speech: it strengthened the blockade camp, because we began to put together a much more coherent and, I might add, strong and logical approach. And... it was after that speech had been reviewed that the majority felt that's the way we should go, and we called the President, who was out on a campaign trip, back to hear our recommendation.

Was there a problem when you were writing that speech, with trying to justify the legality of the decision to blockade?

We felt that the blockade was justified on many grounds: first of all, on grounds of self-defense, which was never outlawed under the United Nations or international law. The Soviets had lied to us about putting on the island of Cuba, 90 miles from our shore, strategic weapons which were not defensive weapons but which were intended for offensive, aggressive military action. That was their only real use, and they were capable of reaching all parts of the United States. Certainly we had to take some action in defense. Second, the fact that they had not announced this as a treaty under international law; they had not gone to the United Nations to say "This is what we are doing," by way of justification; and the fact that we hoped to bring the OAS, the Organization of American States, with us in authorizing the blockade, even in participating in the blockade, all gave us a stronger hand in international law.

On the night of the 22nd, when President Kennedy gave the speech, what was your feeling when you heard him actually saying the words that you'd written, and what was the feeling within the White House at that moment?

The speech was a very difficult one to write, because the President did not want to panic the American public into diving into bomb shelters and petitioning him to surrender. On the other hand, he did not want to panic the Soviets into taking an immediate military response. He didn't want to alarm our allies to think, well, we were shaking about missiles 90 miles off our shore - how were we going to feel about missiles that they were living under the shadow of? It was a speech that had to address many audiences on many different levels. It went through a good many drafts. Just before he went on the air, he met with the congressional leaders, who had been summoned from all parts of the country because Congress was in recess at the time, and all of them were against the speech, against the blockade approach, all of them wanted an air strike and invasion; and it was not surprising because they had not gone through the same thought processes that we had gone through and not seen the same evidence that we had seen.

Nevertheless, the President was shaken, disturbed, angry that they were giving him such a hard time at this last moment. But he didn't change a word in the speech; and a good many of them called in after the speech and said, "Well, now we understand much better why this is the approach that you're taking." I think we all felt in the White House that it was the best approach, it was the right approach. As the President said when he made the choice between blockade and air strike, "This is the limited option, this is the way to begin, and we always have the option of escalating later on, if we must."

JFK addresses the nation on the Cuban Missile Crisis, October 22, 1962, part 1. Theodore Sorensen on Kennedy’s resistance to Congressional pressure to authorize an air strike against Cuba: ‘As the President said when he made the choice between blockade and air strike, ‘This is the limited option, this is the way to begin, and we always have the option of escalating later on, if we must.’

JFK address the nation on the Cuban Missile Crisis, October 22, 1962, part 2: ‘Our policy has been one of patience and restraint…’So, a few days after that speech was given, the blockade was in place, and everyone was waiting, the world was waiting to see what was going to happen to the Soviet ships approaching the blockade line. Do you remember the Excom meeting, or a meeting where you suddenly got information that the ships were stopping or slowing down?

I certainly remember the meeting in which a note came in while we were meeting in the Cabinet Room, which was handed to the President, he smiled and said, "We've just received word that the Soviet ships..." particularly those ships that were most suspect of carrying either nuclear warheads or other missile equipment, had stopped dead in the water. We didn't think it was a final victory: we knew they were probably simply awaiting instructions; we knew that of them had the submarines accompanying them, so that any blockade was a risky choice in its own right. But at least it was a start, it made possible a dialogue, and President Kennedy wanted a dialogue to accompany his use of deterrents.

I believe that Dean Rusk came up with the famous "eyeball-to-eyeball" statement. Do you remember that?

Frankly, I don't. I have no doubt that he did, but I don't remember it.

Was there a sense of relief, though, in Excom? Did you think that you had at least taken a step to bringing the world back from the brink of a possible nuclear war?

No. No, we felt that that was at best a temporary respite. There was much more of a sense of relief when all of the countries of the OAS—the Organization of American States—joined with us, making it a collective action of self-defense, and thereby making clear the legal authority under international law and the United States Charter, that the United States could take this action.

How was the decision taken to stop particular ships, such as the Marakula, for instance?

President Kennedy was very much a hands-on president, and that was true in every sphere of his administration. He was accustomed to calling desk officers three levels down to find out about a particular program, activity or problem. And he was never more hands-on than he was during this crisis, when he, and he alone, made the final decision as to which ship should be stopped and where it should be stopped, and made clear that it was to be stopped in accordance with international law, signaling the flags, the peaceful right to board, and so on. And he did not stop those ships, such as a tanker or a passenger vessel, which clearly could not be carrying offensive weapons, but he did stop those just to demonstrate that we were serious about it, he did stop those from the Eastern bloc countries that could be carrying strategic weapons.

During this period, there was a lot of what came to be known as the "back channel conversations" between Robert Kennedy and the Soviet ambassador. Was that information being relayed to Excom?

Some of it. And we should distinguish now... There were two, or possibly three, meetings between Robert Kennedy and the Soviet ambassador. The Soviet ambassador to Britain was an excellent communications link; he faithfully represented the views of his government and his Chairman, Nikita Khrushchev, but he also spoke and understood English extremely well, and we believe was accurately reporting what Robert Kennedy told him about the American intentions.

Was there any credence given to the conversations that also occurred at that time between John Scali and Alexander Felikskov, also known as Alexander Formin?

Formin... There were two restaurant meetings between ABC news correspondent John Scali, a very good State Department correspondent, and Alexander Formin, who was a KGB representative in the Soviet Embassy in Washington. I'm not sure that I would escalate that to a level of back channel in terms of dealing, but it ultimately confirmed the message we were getting from Khrushchev about a possible solution to the crisis.

Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin and JFK: Robert Kennedy met with Dobrynin to personally hand him a letter from the President. RFK had been instructed by his brother to warn the Ambassador that the U.S. would commence air strikes if a reply was not forthcoming in 24 hours. Theodore Sorensen: ‘The final meeting between Robert Kennedy and Ambassador Dobrynin was absolutely essential to the peaceful resolution of the crisis.’But let's go back to the Robert Kennedy... even though I'm not sure here about the order of your questions. The final meeting between Robert Kennedy and Ambassador Dobrynin was absolutely essential to the peaceful resolution of the crisis. A group within the Excom sat with the President when Robert Kennedy was instructed to carry to the ambassador, to hand-carry to the ambassador, our reply to Khrushchev's letter of the previous day, Friday, and to tell him two things: one, the time is growing very short, that those who were of a different mind to those who wanted an invasion or an air strike, were growing in their ferocity, and that the United States, if the blockade did not prove to be a winning remedy, would have to take other measures very soon; and second, to tell him that the bases in Turkey, which had been the subject of the second Khrushchev message that had so discouraged us all, were a problem that the United States had always intended to take care of. The President did not believe that those missiles should stay in Turkey—not for the same reasons the Russians wanted them out, but because they were outmoded, anachronistic, and could be replaced by Polaris submarines in the Mediterranean, and we could not take them out at the point of a gun, we could not take them out under threat, we could not take them out unilaterally, because they were NATO bases, but he had our assurance that they would be gone provided it was not done on a quid pro quo basis and therefore the Russians could not talk about it. The deal was simply they would pull out the missiles, we would pull back the naval quarantine, and not invade Cuba, which we had no intention of invading anyway. And it was that extra oral message, along with our letter, that I believe had a great deal to do with Khrushchev's agreeing to those terms.

If I can lead you back just slightly in the chronology. The first message that you received from Khrushchev was a long telegram, which you received on the 26th, I believe...

Well, yeah, it wasn't the first, actually.

No, well, first sort of official statement. Could you just tell me a bit about the messages that were coming out of Russia?

Yeah. During this... terrible week—terrible in the sense that two superpowers were on the brink of a nuclear war, and one false move could have precipitated the destruction of the world—during that terrible week, the channels between Kennedy and Khrushchev were kept open. These were channels which had begun in the fall of 1961, and that was a very good thing indeed. The messages ... the letters came from Khrushchev, responded to by Kennedy, and it was a way of keeping them engaged, it was a way of probing, of exploring. And finally, on Friday night, came this long message, in which Khrushchev, while somewhat wandering all about the message contained the germ of a solution. And putting the best face on it, and reading it the way that we wanted to read it, so to speak, it said in effect: "We will withdraw those missiles from Cuba if you promise not to invade Cuba—because that's why we put them there—and if you withdraw your quarantine, and let's stop... both sides draw back from this hair-trigger alert that could simply destroy the works on both sides." And while we were discussing that letter, and whether that was a solution that could go forward, we received a second, public message from Khrushchev, which didn't talk about that solution, which had a very harsh tone to it, which said that we would have to give up NATO bases in Turkey if they were to withdraw their missiles from Cuba, and which sounded to us as though it had been approved by his military staff or some larger group, the Presidium or otherwise, and put us in a dilemma, because it was so different in tone from the letter of the previous night.

So when Kennedy heard Khrushchev's harder ... the second message, was there a sense of almost blackmail from Russia? How did he respond to that message?

Well, Kennedy was very disturbed by the second message. First of all, he was disturbed to know that those missiles were still there, since the previous year he had learnt that they were anachronistic, unreliable and unnecessary because Polaris nuclear submarines would be coming into the Mediterranean to replace them. But they were still there. He was disturbed because there was no way we could unilaterally take them out, and there was no time to gather a NATO conference to take them out. He was disturbed because we could not take them out with a gun pointed at our head, or we would be admitting our weakness to the world and to our allies who had a stake in those anti-Soviet missiles as well. But finally, he was disturbed because he said, "If we ignore this and we proceed into a world nuclear war, what is history going to say about what they will interpret as a very reasonable offer that we rejected: they'll withdraw their missiles if we'll withdraw our missile." We couldn't do it, and yet he thought we were in a terrible box here.

So what was the solution?

The solution, finally, was to respond to the first letter and largely ignore the second. And the President asked me to go back to my office, asked the Attorney General to come with me, and to prepare a letter... I'd had the primary responsibility for answering all of these Khrushchev messages during the week for the President's signature... and to prepare a letter which interpreted the previous night's letter as a solution that we could accept, and so worded, and simply say: "Other disarmament measures can then be discussed after this crisis has been resolved." And that was the letter that Robert Kennedy took that evening to the Soviet Embassy.

The following day, the 27th, the U-2 was shot down over Cuba...

No, no, that was the same day.

Same day—beg your pardon. What was it like when the U-2 message came through?

I have to say that during the time that we were debating these two letters, the picture became even more grim. Not only was the second letter casting a pall over the one possibility of hope that the first letter had offered, but at the same time the intelligence reports said that the missiles are now operational and ready to be fired; other ships were proceeding right toward our quarantine barriers, with submarines accompanying them—that meant a possible naval shoot-out. One of our low-level surveillance planes had been fired upon, which could have meant either Russian or Cuban troops at that level. And worst of all, one of our U-2 planes had been shot, the pilot had been killed, he'd been shot down by a Soviet SAM—surface-to-air missile—and we had taken a policy decision earlier in the week that because surveillance was so important, that if that were to happen we would have to respond by bombing a Soviet surface-to-air missile, and that could have escalated the entire situation.

What were your personal feelings at the time? Were you worried about your family, your own sort of safety, Washington's safety?

I think we, for the most part, were all too intent upon finding a solution to give much concern to personal worries. Some members of our group sent their families outside of Washington, which was likely to be a target. I had no family living with me at the time. The President had joked with me the previous Saturday, after the decision had been made, that there wasn't room for all of us in the White House bomb shelter, but I had a place there if it came to that. But my strongest feeling was of admiration for the President of the United States, who kept cool—the calmest man in the room. And when they said, "Well, we've got to go bomb that Soviet SAM site," he said, "Let's wait, let's wait until we have more information about it, let's wait until we see what the response is to our letter," because he knew the United States dropping a bomb on Cuba could start almost anything.

The following day, the Sunday, the message came through, the first radio-message from Moscow, again saying that Khrushchev was prepared to remove the missiles. Could you tell me how you heard that, and what happened next?

I was accustomed each morning to wake up on the hour and turn on the news to see what was the breaking news, if any, about the crisis. And the first news I heard on Sunday morning, when I woke up after a very rancorous Excom meeting Saturday night, after the messages had already been sent off to the Soviets... of course, the top of the news was this broadcast from Khrushchev over the open air, that Soviet missiles were to be withdrawn under inspection, and the crisis was over. I could hardly believe my ears. I called the National Security adviser, McGeorge Bundy, at the White House. He said, "Yes, it is true, we have received that message, we have verified it, and the crisis is over. Our group is meeting at 11 o'clock, and meanwhile the President and First Lady have gone off to church to thank God." And we gathered for the 11 o'clock meeting; everybody was in smiles. I was standing with the President, talking with him in his office just before we went into the Cabinet Room for the meeting, and one of his other National Security assistants came up to him, who had not been deeply involved in the crisis preparations, and he said, "Now, Mr President, you can step in and solve the India-China war," because the war between India and China over the border had broken out at the same time. The President said, "I don't think either of them, or anybody else, wants me to solve that crisis." And the aide said, "But Mr President, today you're 10 feet tall." And JFK said, "That will last about a week."

Would you say that those two weeks earned Kennedy his place in history?

Yes, because even though the Cold War went on for some years, the tide turned during that October 1962. A British historian once compared it to the Ancient Greek stand that preserved civilization in the earliest ages. People no longer thought that world war between the Soviet Union and the United States was inevitable. They no longer thought that the only solution to the very real conflicts of interest between Washington and Moscow was to look down the nuclear gun barrel at each other. In the following year, we set up the Hot Line between Moscow and Washington; we agreed to explore outer space together, and to ban mass weapons of destruction from outer space; we agreed to have the first sale of American wheat to the Soviet Union; and most importantly, we took the first step toward arms control in the nuclear age, which was the limited nuclear test ban treaty. At the United Nations, in September of 1963, Kennedy's speech was a speech on peace and all the next steps that we and the Soviet Union could explore together in order to tamper down and ultimately end the Cold War. And then, unfortunately, he was killed.

Supposing that statement hadn't come through on the 28th, that Khrushchev was to pull out the missiles, what do you think would have happened?

There were those on Excom who wanted us to go immediately to air strike and invasion. The Vice-President of the United States said in that rancorous meeting of late Saturday night, "When I was a boy in Texas, walking along the road, and a snake raised its head, there was only thing to do, and that was to take a club and cut off its head." But there were others on Excom who were determined to find other limited means of turning up the pressure without precipitating war—because we now know that war would have come, that had there been a bombing and an invasion, those missiles might very well have been fired, and at the very least, Soviet troops on the island of Cuba would have fired tactical nuclear weapons which they possessed at the invading American armies, and we would have felt compelled to respond with nuclear weapons ourselves. So there would have been ways of tightening the blockade to include so-called POL—petroleum oil lubricants—which can shut down a country's economy; there would have been bans on air flights to Cuba; there would have been other avenues to explore peace through the United Nations, which President Kennedy discussed with Dean Rusk. I think that we had a President who was determined not to go to war, because he felt that meant the failure of everything he was trying to accomplish.

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024