The Blogging Farmer

Alex Tiller’s Blog on Agriculture and Farming***

‘Oh, The Farmer and the Cowman Should Be Friends...'

Ever see the musical Oklahoma?

Okay, it's thin on plot (though the songs are memorable—and one even went on to become an official state song), but it dealt with one interesting issue, which was the conflict between cattle ranchers—who during the period of the show (early 1900s), required hundreds of acres of open, unfenced land—and farmers, who by necessity require fences and boundaries.

In a way, it reminded me of a story in the Book of Genesis. Abel, as you might recall, was essentially a cowman. (Actually, he herded sheep and goats, but it's the same principle.) Cain on the other hand was a farmer. When it came time to offer up a sacrifice to their common Deity, Abel put a lamb on his altar, which was acceptable, and Cain offered his produce, which was not. This made Cain a little upset (and why not? He worked his butt off to grow that stuff and pull it out of the ground).

You know what happened next.

Now, a lot of religious scholars, Jewish, Christian and Muslim, have had their own takes on this story over the centuries. Most Sunday School teachers simply tell children that Cain was jealous because God liked Abel better. On the other hand, some rabbis, using a method of interpretation called Midrash, figure that there was jealousy over a woman involved. Other interpretations peg Cain as being just plain evil. But I think all of these people are missing the real point of what this story is about.

With all due respect to the devout among us, I'd like to step out of that religious viewpoint and look at it as an anthropologist or paleontologist might.

Often, what we all like to label as "conservative" and "liberal/progressive" are just words for "old" and "new." (Stay with me here.) For example, the word "pagan" really means "country/rural people" who practiced old ways of doing things. Back in the day, when the first Christian missionaries were heading into the back country of Iron Age Europe from the cities of the Roman Empire, their religion was considered something "new." It threatened those in the countryside who followed the "old" ways.

Cain and Abel: A conflict between ‘new agriculture’ and the old herding/ranching lifestyle?Now, let's back up another 8,000 years or so. At one time, all people were hunters and gatherers. After awhile, hunters started following herds; eventually, this became what we know as ranching. This is the way people got a lot of their food for thousands of years.

Nobody knows for sure when people figured out how to plant, tend and sow crops. What we call the "Angricultural Revolution" seems to have started in several places at different times—and you can be certain that it didn't happen overnight. Nonetheless, agriculture was at one time, a "new thing"—and because it required fences and a strange new concept known as "private property," it wasn't long before the new agriculture came into conflict with the old herding/ranching lifestyle.

What if the story of Cain and Abel is a metaphor representing this conflict? Since farming was a "new" thing, and therefore threatening to the status quo, it shouldn't come as a surprise that Cain got a reputation for being a bad guy (fact that he murdered his own brother notwithstanding).

This same tragedy was played out in the American West during the latter part of the 19th Century; the "range wars" are a part of our history (the 1953 movie Shane was set against on such conflict). Eventually, the government had to step in to make sure that farmers and cowmen could work together and play nice.

Frederic Remington captured many scenes for Harper’s Weekly magazine during a months-long visit to Punta Gorda in 1895. This one, titled ‘Ambush,’ documents the drama of a range war murder.So—we've established that at some point, about eight to ten thousand years ago, a new thing called "agriculture" butted heads with an older, herding lifestyle. If the story of Farmer Cain and Herder Abel represents any sort of historical metaphor, things got very violent back then (just as they did in the American West during the 19th Century).

Here's the thing; farming is a much more efficient way of producing food. You can feed a lot of people on a relatively small patch of ground (see my entry of 25 June). Ranching on the other hand normally requires a lot of land. Those cattle ranches in Texas and sheep ranches in Australia that could take you two days to drive across weren't that size by accident—they needed to be that big.

In Europe, there wasn't that much land available. Therefore, beef was an expensive delicacy, enjoyed only by the well-off and on rare occasions, by the middle class and working families (and usually stretched with other ingredients such as grains and vegetables). Then, around 1500, the Spaniards started arriving in America droves—and noticed that there was a lot of empty grassland. (It really wasn't that empty, but the hunter-gatherer Indian tribes and the buffalo that sustained them apparently didn't count.)

It's no coincidence that words such as ranch (ranchero) and buckaroo (vaquero) are from Spanish. They pretty much invented the American ranching industry.

By 1890 however, a lot had changed...and in the age-old conflict between agriculture and herding, farmers finally got the upper hand. (A lot of people don't realize that the "Golden Age of the Cowboy" lasted only about 20 years.) Meanwhile, Americans had developed a real taste for inexpensive beef. Problem was, there wasn't a lot of room to raise cattle anymore.

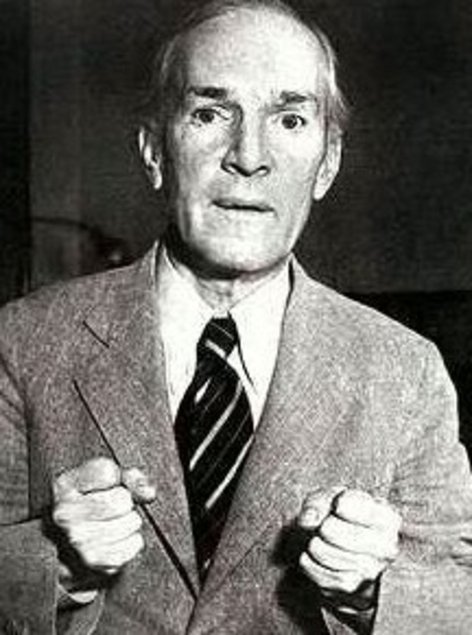

Upton Sinclair’s 1906 novel, The Jungle, graphically depicted the problems of factory farming.The solution, as you know, was factory farming. This led to a whole lot of problems in the beginning, which was graphically depicted in the 1906 novel The Jungle, by Upton Sinclair. Did you know that most U.S. military casualties during the Spanish-American War were due not to enemy fire, but tainted meat (gleefully sold to the Army by the Armor Meat Company)?

Teddy Roosevelt and his Administration did a lot to clean up the meat packing and processing industry side of things, but when it came to raising beef cattle, the operation by necessity got more and more concentrated.

If you have ever seen one of those factory farms, you'd probably swear off beef forever. I remember seeing (and smelling) one when I drove through a little town several years ago.

As awareness of the problems of such factory farming (not the least of which is animal cruelty) becomes more common, people in the U.S. seem willing to vote with their pocketbooks, buying free range beef. It costs a lot more, but it's better for the animals, better for the land—and better for you.

I'm not a vegetarian, and I have no problem enjoying a steak, roast beef or hamburger now and then. With all due respect to vegans, if meat consumption is such an evil thing, can I ask what you're feeding your pet cats and dogs? Are you going to condemn wolves and cougars for bringing down deer and elk for dinnertime?

What I am saying however is that perhaps beef shouldn't be a primary source of food for humans. Unlike members of the cat family and other carnivores, the human digestive system is set up to handle a wide variety of foods, primarily fruits, nuts and vegetables. We can produce a lot more of those for a lot more people than we can beef.

That said, when you do buy steak and hamburger for those special occasions, spend a nickel for quality and humane treatment of cows—and support your local free-range rancher.

Posted on August 24 and September 11, 2010

***

Hello, and thanks for checking out my blog. My name is Alex Tiller and I grew up in rural Ohio (Clark County) where my family still owns farmland (corn and beans). I am a member of the American Society of Farm Managers and Rural Appraisers and am also an agribusiness author/blogger. I write about commercial farming, family farms, organic food production, sustainable agriculture, the local food movement, alternative renewable energy, hydroponics, agribusiness, farm entrepreneurship, and farm economics and farm policy. I visit lots of farms in different areas of the country (sometimes the world) that grow all kinds of different crops and share what I learn with you through this blog.

You can contact me via email by clicking here: Email Alex (http://blog.alextiller.com/contact)

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024