Hank Williams, ‘Cold, Cold Heart’‘Presenting The One And Only Lovesick Boy, Hank Williams!’

In one impressive 16-disc box set, all the surviving Mother’s Best Flour shows Hank Williams hosted in 1951 are gathered for posterity and lasting pleasure. It’s a tossup as to whether the shows’ survival or Hank’s performances are more miraculous.

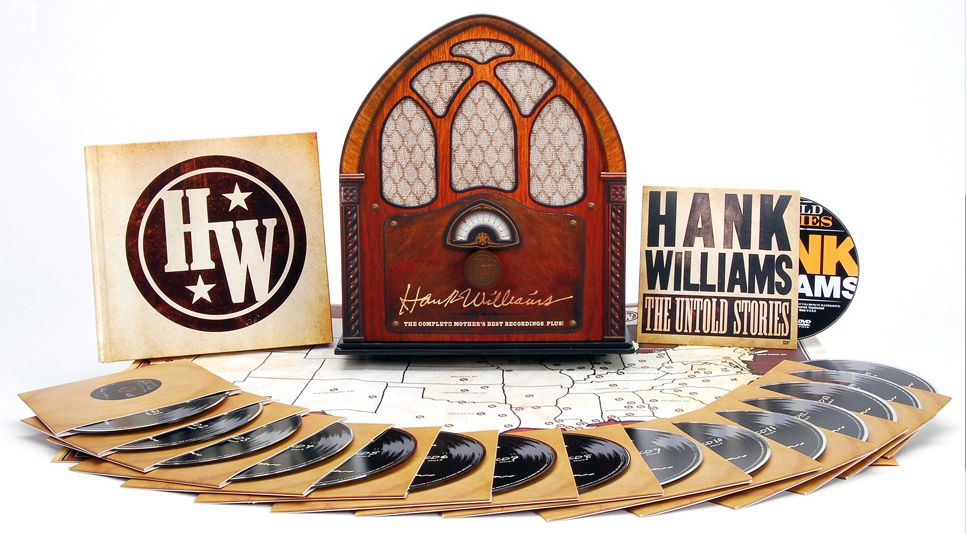

By David McGeeIf it didn’t have the signature of Hank Williams and the subtitle “The Complete Mother’s Best Recordings Plus!” on its front side, you could easily mistake the packaging of the spectacular 16-disc box set for an old-time radio. In fact, if you turn the knob on the front to the right, it clicks on and a commercial for WSM plays, followed by Hank himself singing “Lovesick Blues.”

It adds an element of novelty to what is otherwise a serious historical document: 72 complete 15-minute shows, sponsored by Mother’s Best Flour, comprising 143 Hank performances from 1951 (with one final show from Spring 1952 on CD 15), on 15 CDs and one DVD (featuring two now-deceased members of Hank’s band, Don Helms and Big Bill Lister, reminiscing about their boss’s music and life). Dedicated Hank fans and historians will recognize some of these shows—54 tracks were included on the 2008 three-CD collection, The Unreleased Recordings, and another 54 were collected on 2009’s three-CD set, Revealed. This new box set presents the most complete picture yet of Hank in 1951, loose and relaxed, although sometimes in pain from his back problems, so much so that he had to perform sitting down at times (and he lets you know he’s not in good shape—one of the special qualities of these shows is their seeming informality, as if Hank were chatting up friends in confidence). Gospel songs, folk songs, blues, novelty songs, sentimental songs—a virtual American roots songbook, featuring only a handful of the tunes that made Hank a legend, and more of the stuff that made him a unique, influential and timeless American artist—the foundations of a growing nation’s voice in song, a reflection of its values and abiding faith, and not incidentally, of its warm, generous humor and unwavering civility. It’s hard to listen to these shows and not lament the loss of something important in our popular culture, even as we have become a more inclusive and tolerant nation.

That these shows were saved for posterity, though, required some good luck. The acetate discs, which were by design intended to be played only once, were in the possession of radio station WSM and about to be discarded, along with other archival items deemed to have little historical value, when they were retrieved from a dumpster by an alert employee. The second stroke of good fortune occurred when the late, great audio engineer Bob Pinson had the foresight to transfer the acetates to tape in 1981, a move for which he is recognized in the liner notes in a heartfelt thank you from Hank historian Colin Escott, who is also responsible for the liner book, and the superb audio engineer at the Country Music Hall of Fame, Alan Stoker, who performed a similar retrieval of historic proportions in 1987 with The Bristol Sessions, the 1927 Ralph Peer-supervised Victor auditions that launched the careers of Jimmie Rodgers and The Carter Family, and with them the modern country music era.

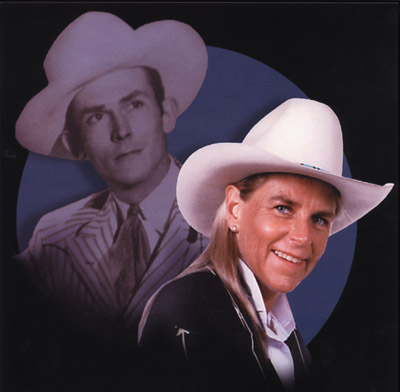

Without these gifted men on the technical side, the Mother’s Best acetates might have remained in safekeeping with Hank’s daughter, Jett Williams, who is herself a story. Born Antha Belle Jett on January 6, 1953, Ms. Williams is the daughter of Hank Sr. and Bobbie Jett, the latter having had a brief relationship with the artist in between his two marriages. Born five days after Hank’s death, she was adopted by Hank’s mother Lillian Stone and renamed Yvonne Stone. After Lillian’s death in 1955, she was made a ward of the State of Alabama. “Most of you probably know the saga of my life,” she writes in her note in the accompanying book in the box set. “I was lost for years in the abyss of orphanages and foster homes. I was entangled in a legal system that was supposed to have my best interests at heart, but didn’t.” In 1984, with the help of Washington, D.C. investigative lawyer Keith Adkinson (whom Jett later married), a pre-birth custody contract was located and a year later the Alabama State Court affirmer her as Hank Williams’s daughter; in 1987 the Alabama Supreme Court went a step further and ruled that she was entitled to her half-share in the Williams estate, a ruling Hank Williams Jr. appealed in federal court but lost when the United States Supreme Court refused to hear the case in 1990. A 2005 Tennessee Court of Appeals ruling upheld a lower court ruling giving Jett and Hank, as their father’s heirs, the sole rights to sell the recordings Hank made for WSM and Mother’s Best Flour, in a case that pitted the country icon’s offspring against Polygram Records and Legacy Entertainment. Having prevailed in two tough legal battles—first to prove that she was who she claimed to be, and then for control of her father’s recordings—Ms. Williams finally has the standing some would have denied her, and has become an articulate, credible spokesperson for her father’s legacy.

Speaking by phone from Nashville recently, Ms. Williams discussed the tangled history of the Mother’s Best recordings and what she’s learned from them about the father she never knew in life but with whom she is on intimate terms through the music he left her.

***

‘It takes you back to 1951, and in a way, after you start hearing it, you really don’t want to come back’Jett Williams retraces the long and winding road of her father’s Mother’s Best recordings

Of the many amazing facts about the Mother’s Best recordings, what stands out for me is that WSM was trying to throw them out, and only a sharp-eyed employee—a photographer for the Grand Ole Opry in fact—stood between them and oblivion. That’s nothing short of a miracle.

You got it. And as bad as that is, a person can only image what actually did make it out the back door to the dumpster. I heard there was a lot of sheet music, a lot of things they were discarding when they were making that move. I don’t know that anybody was thinking about more preservation than commercialization. Yeah, they were getting ready to be discarded.

You know it’s taken awhile for everybody to realize that once all this material is gone, it is gone. When you say nothing short of a miracle, I believe this is a true miracle. They made it past the dumpster, then the chain of custody it had to travel through, and all of this time, from ’51 to whenever, these discs were not exactly stored in the best condition for preservation. And what we’ve been able to take from the transfers is as good if not better than the MGM masters, for the most part. So to be able to come out at the very end of the deal and have the quality come off of these acetates is just remarkable.

Are there shows or parts of shows missing because they could not be retrieved?

We did all the acetates that we had—the 72 shows. And plus you’ve got the Aunt Jemima demo and the public service announcement too.

So the audio restoration process was tremendously successful—it got everything back.

It got everything back, it sure did. The gentleman that was the engineer, Joe Palmaccio, I was talking to him the other night when I did the Eddie Stubbs radio show. Colin Escott came and I was talking to him and we were laughing that Hank didn’t need Pro Tools. I said this on the air, regarding one of the processes that we did that was fascinating, on these acetates you had to use a different needle. When these acetates were cut, grooved out, they would get a box of needles, different gauges, and sit there and play it, and change the needles out to see which needle could actually get in and grab the best sound off of it. These things are very delicate and they were made to be played only one time. It was fascinating to be in on that process. We’d close our eyes and all vote, by our ears—instead of the modern technology it was, “What is the listener going to hear out of that speaker?” And as far as the transfers, one thing they tried to do was bring everything up basically to the same level, so when you went from one show to the next show, that there was some consistency in the level, as opposed to one being down, one being up. Then if there were any pops or hisses, we were able to remove those. Nothing was really done to the integrity of the recordings. As far as going in there and helping ol’ Hank, we didn’t do that.

It is remarkably consistent audio quality and it puts you in awe of the audio restoration technology, that we can preserve these things with such good fidelity.

Plus there were a lot of good ears, too. A big factor, as I said, was “What is a person going to hear?” not necessarily what the machines were telling us. It’s that listener you want to smell the biscuits and the coffee, and when you turn your radio on it’s just like Hank's right there with you.

The other thing I found fascinating is that the acetates played from the label out, rather than from the outside in. And those acetates are really very delicate. In one of the processes I saw, they tok a sponge, and some Dawn and water to the discs, and I’m going, “Wait a minute!” And Alan Stoker had a dehydrator, just like what you buy at Walmart. I said, “What you cookin’? Venison or something?” He said, “No, the tapes.” “You mean, in a regular ol’ dehydrator?”

Also, Alan and Joe have such a love for this. And with this you have to love it and you have to be very, very good at it. This whole process with Time-Life and everyone else, it is the music business, and money, whatever, is a factor. But this has gone so far beyond that—the dedication, the pride. When you look at the box set and everything that went into it—the detail, I’m in awe. I know I was a part of this thing, but I am so proud of the way everything turned out and the way everyone climbed on board and became a team. Someone said, “We know in our lifetime this may be the most special project we ever get to work on.”

A little deeper background on this. You fought a long legal battle to establish legal ownership of this material. When did work on this collection begin?

I’d have to talk to my husband, who was the attorney for the estate for the specific date. I’m guessing it was five years ago. Les Leverett was the gentleman who got possession of the acetates, and from there some, not all, were transferred to reel-to-reel and given to Hillis Butram, who was a Drifting Cowboy, but later—he wasn’t on the radio show—so he could see what he could do with them. When I emerged, so to speak, in the ‘80s, Les Leverett gave me the acetates. But I was in litigation against the publishers and Hank Jr., so we put it on hold. When we got through that litigation, by then Hillis had sold a copy to a company in Texas. They were getting ready to release some of these recordings, but they had gone in and lifted my dad’s voice, put a new band behind him and said they owned it. Hank Jr. and I joined together, because we are the estate, and we got an injunction to stop this travesty. We ended up suing this company to prevent them from doing anything with this bootleg copy. In the meantime, Polydor and Polygram, which had bought MGM Records, jumped into the fray and said, “We own them because Hank signed a master recording contract with us.” We’ve got the estate saying they belong to the estate of Hank Williams; the record company saying, “No, they belong to us”; and you’ve got this record company out in Texas saying, “We paid for a copy and we own it.” So the courts here in Tennessee, in Nashville, ruled that the estate owned the recordings. The other two parties appealed it, and it went to the Supreme Court of Tennessee, which upheld the lower court ruling that the recording belonged to the estate. The court said Polydor, MGM, owns only what they paid for in the master sessions. That’s all the contract called for—“you don’t have ownership to anything he did outside of your contract.” With the acetates, the courts ruled that my dad’s contract called for him to let this be recorded and played one time. So when it went out that one time, he fulfilled his contract. Anything that else that was done with it belongs to him. And that was the ruling. You don’t even have to have the acetates because it’s intellectual property. It’s just very fortunate that we have possession of the acetates.

So when you had the acetates, did you have the means to listen to them? Did you know what was on there?

Yes, I did, I have one of the tape copies. By the time they came into my possession, of course I was told they weren’t meant to be duplicated, so I was given a cassette. Les Leverett gave me more acetates than anyone else had ever heard; some of them had never been transcribed. Until it came time to actually transfer them as part of this project, my husband and I did not allow anyone to play the original acetates, because we didn’t want to do any damage to these discs. But I listened—I about wore ‘em out, I’ll tell you that.

Hank Williams, ‘Hey Good Lookin’On that point, I wonder if recordings such as these, as opposed to the famous studio recordings we’re all familiar with, give you a better understanding of your father?

Oh, absolutely. Twofold. Look at the song titles. At that point in time he did not have enough of his own personal hits, so he was reaching into his bag of songs that he had written but had not recorded; he was singing gospel songs, PD songs, songs by other artists. I think that selection of music he has on these discs gives you an insight into what kind of music Hank liked to listen to outside of what he wrote. When you’re looking at “Blue Eyes Crying In the Rain,” and those songs, I think they give you a sense of what he liked, if it wasn’t his songs. The other thing being the difference between the MGM mastered version of a song—say, “Cold Cold Heart” or “I Can’t Help It”—to what we have on this live performance. These performances, because they are live, there are no filters, they haven’t been done as a master, which I think takes away a little bit of the magic and intensity of what we have; when he sings that one-time take, he sings like his life depends on it, and there is so much—some of those are even better, when you go back and listen to a master version. Someone’s worked with what you hear on a master; on this, it’s just right there and that’s it.

Are there favorite tracks on this collection that maybe touch you in ways that others don’t? Something that strikes a deeper chord for whatever reason?

My personal favorite as his daughter is when he sets the song up and sings “On Top of Old Smoky.” The reason for that is because he sets the song up by saying he’s going to sing the top tune in the country. But instead of singing it in the style that everyone’s hearing, he’s going to sing it the way his grandmama did when she put him to bed. So for me, that’s a piece of my family history. Now when I hear him sing that I have a memory in my mind of my dad as a little boy and his grandmother sittin’ on the bed, tucking him in and singing to him. So for me that’s personal. Professionally, the one that really gets me is when he sets up “I Can’t Help It.” Because he says, “No one’s ever heard this song except me and the record company. And I’ve never sang it live before.” And then he sings it. I can only imagine writing a song, you’ve just recorded it, the world has not even had the opportunity to hear it, and this is the very first time. That has to have very powerful emotions for the artist/writer, I would think, to take a breath and sing the song for the very first time on the airwaves, hoping everyone will sing it and dance to it and fall in and out of love over it.

You not only fought this long legal battle to get the ownership of this material, but even before that you had to fight to prove who you are. It took awhile, but now it’s in the past and here we are. Do you feel you’re fully accepted now? Is anybody questioning now that you are who you say you are?

Absolutely not. And when I walked out to the show with Eddie Stubbs at the Country Music Hall of Fame the other night, I got a standing ovation. I spent, well, these past however many years, but these past four years intensely on spearheading and being the executive producer of this box set. I’m very proud as Hank's daughter to be in a position to be able to work with such wonderful people as Time-Life, to be able to take my dad’s recordings and share them with the world. I was so honored to go as his daughter and receive the Pulitzer Prize for him in New York this past May.

Jett Williams: ‘I think maybe everybody’s had enough of too much and people are starting to focus. Hearts are still breaking the same way—that won’t change, ever, and that’s why those songs are not time sensitive. You can sing it today and you can sing it tomorrow.’So the big question is, are there still more unreleased Hank treasures yet to come?

Still got a couple of things. But this is the magnum opus. The other stuff is earlier recordings with Hank and Hezzie ([Ed. note: “Hezzie” is comic Smith “Hezzie” Adair, one of Hank’s original band of Drifting Cowboys); we’ve got a concert performance, where he’s actually doing a show, and it’s kind of neat. But these Mother’s Best shows have been floating around since 1951—from ’51 to the ‘60s they were sort of in the box to be deep-sixed, and then when they were getting ready to be discarded the tape started floating around. So the thing about the Mother’s Best recordings, they’ve been well known and around, but what we wanted to do was to be sure we captured the magic and do a presentation and packaging that would do this project proud. This goes to love, dedication and pride. We figure there is about ten minutes of interview with my dad, and little or no actual interviews. He’s an eight-by-ten and an MGM record. Here, when you go through and listen, you see this man who is not one-dimensional. He’s the whole package—he’s an MC, he tells jokes, he’s a backup singer, he does instrumental solos. He’s an all-around performer, not just the hit artist we see in that picture. And you hear him laughing at mistakes, and you hear him make fun of himself. Also, there’s parts where you hear the pain in his voice when he’s trying to get out of the chair—he had just come back from back surgery. You can hear the homesickness in his voice when he talks about Alabama. And you can hear how fast he is, because it’s not really structured, the banter that’s going on. Hear him talk about current affairs, and you can hear how intelligent he is, how he keeps the show on track, a completely different side of Hank Williams. He’s very relaxed, very friendly, very authentic. It takes you back to 1951, and in a way, after you start hearing it, you really don’t want to come back.

The other thing, too, is that my dad’s music, and my dad, supersede country music. The Pulitzer said he elevated country music into a universal music. My dad, when he sings those songs, whether they’re his or not, they’re still here, sixty years plus. I maintain that this music, this box set, is generational. “I remember where I was when your daddy died.” “My mama loved your daddy!” Also, I’m really pleased at the younger generation zoning in on Hank. I think maybe everybody’s had enough of too much and people are starting to focus. Hearts are still breaking the same way—that won’t change, ever, and that’s why those songs are not time sensitive. You can sing it today and you can sing it tomorrow.

Hank Williams, The Complete Mothers Bet Recordings Plus! is available at the Time-Life Hank Williams site, http://hankwilliamsmothersbest.com/details.php

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024