‘The Magic of His Thing Is Simplicity’

An Interview with Peanuts Comic Book Artist Dale Hale

By Nat Gertler

Copyright 2000This interview originally appeared in issue 8 of Hogan's Alley, a magazine of the cartoon arts and is posted online at AAUGH.com, http://aaugh.com/guide/ldale.htm. Published in October 2000, the printed version included pictures of Dale, examples of Dale's work, and copies of some of the interesting pieces from Dale's personal collection.

Long after new material started being created to fill comic books, there were still comic books produced the old-fashioned way, featuring color reprints of newspaper strips. Comic strip syndicate United Feature also published comics such as Tip Top, Tip Topper (no Tip Toppest is known to exist, alas) and Fritzi Ritz, filled out with various UF features. Reprints of the then-young strip Peanuts were added to those magazines starting in 1952, and there was a single issue of an all-reprint Peanuts title in 1953. When St. John took over the UF comic book titles in 1955, they continued using the same content, simply re-reprinting the same Peanuts strips that UF had already reprinted.

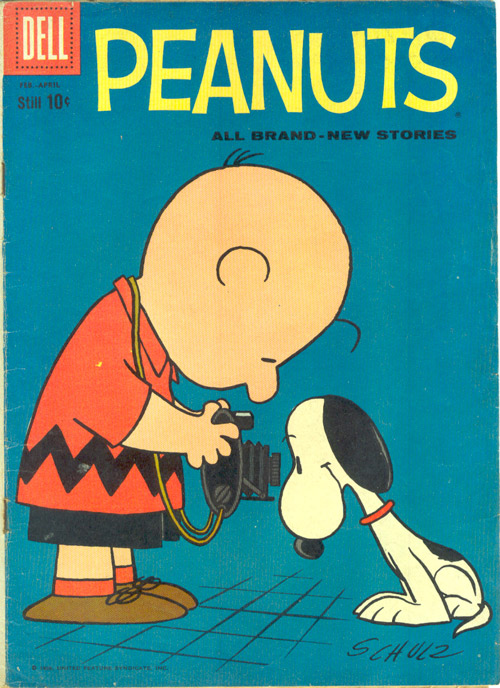

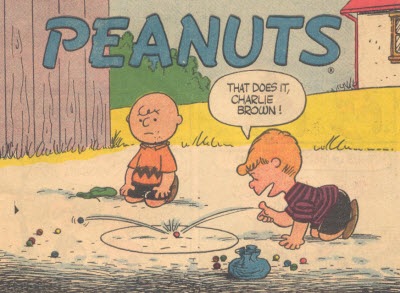

When Dell Comics took over the line in 1957, however, they chose a completely different direction. Instead of reprinting and re-reprinting newspaper strips, they decided they wanted brand new stories created just for the comic books. Peanuts creator Charles Schulz (known as "Sparky" to his pals) agreed to have the material generated from his studio, with the help of his talented friends Jim Sasseville and Dale Hale. Beginning with short features in Nancy, Fritzi Ritz and Tip Top, Dell eventually experimented with having some issues of Four Color bear the Peanuts title. After three of those, Dell moved Peanuts to its own title.

After his artistic studies, Dale Hale became Charles Schulz’s assistant on Peanuts for several years. Afterwards, he moved to Santa Monica, where he spent eight years writing and drawing The Flintstones and Yogi Bear daily comics. He then began his own syndicated comic, Figments, which was published in newspapers around the world for 15 years. He also began the cartoon panel You’re Getting Closer for King Features Syndicate. Hale has written for animated shows such as Road Runner, Pink Panther, Flintstone Kids, Flipper, Ghost Busters, Broom Hilda, Duck Tales, Tiny Toons, Shelley Duvall’s Bedtime Stories and many others. He has also worked in design and development for several companies.

AAUGH.com interviewed Dale Hale in the studio behind his lovely house in Santa Monica, California on Friday, January 7, 2000, about a month before Schulz passed away.

How did you get involved with Schulz and with Peanuts?

When I was graduating from college, I was out in the Midwest and I went back to Minnesota about six weeks before graduation to look for a job. I was an art major. Cartooning was my specialty. I went to the newspapers—they didn't want editorial cartoonists—just to get the lay of the land. And somebody said, "You oughta go over and see this cartoonist named Schulz. He's over in the top of a building: Art Instruction Incorporated." I don't know if you remember them, but they used to have the "Draw Me" matchbook covers.

So I went over there, and the receptionist called him and he said "sure, come on up!" I had a portfolio of stuff and he looked at it and said, "Well, I don't use an assistant, but the people downstairs might like your stuff." He took me downstairs to Art Instruction and they liked my stuff. So I had a job waiting for me when I came out. Went to work there for about six months. Had a commission in the service through the ROTC and did my six months—it was six months in those days then you were in the National Guard for the next 200 years. You went in and learned your specialty as an officer.

Then I came back and worked for Art Instruction for another six months. They'd given Sparky a little penthouse, a little building on the top of the building as his studio, and then in turn I think they used his name: he was "cartoonist consultant.” And before, I think he'd worked for them.

Yes, he had.

Sparky and Jim Sasseville (who also worked at Art Instruction) and another guy by the name of Tony Pocrnick, the four of us used to go down at lunchtime and shoot billiards. It was a little place right next door, and he loved billiards. So the four of us would go down there every day for all the time I was there, and got to be good friends. Then one day he said, "My wife and I are thinking of moving to California, and are you and Nona" (my wife) "interested in moving out and you can work as my assistant?" It was nice. [laughing] "Yeah!" Because I knew from the time I was 12 years old growing up in the Midwest I wanted to live in California! I remember walking through a snow bank that deep [holds up hand] telling my father "I love you, but I'm moving to California." And so we moved to California.

I guess I knew about three months before, and my wife and I had no children at the time. We were cruising around Minneapolis in a little white Corvette, footloose and fancy-free. We took off about a week before they did, with all their kids, and came up to Santa Rosa. We scouted out the place, and he said, "We'll bring your stuff in the Bekins truck and you guys go on out and let us know what you think of the place." He bought 28 acres of redwoods with a beautiful house outside of Sebastopol. It had a nice studio; I remember the man, I think his name was Rollo Watts, who was quite a well-known photographer. He bought this property from him, and he was getting quite old. The studio was just perfect for a cartooning studio. So we went out and called him back and told him "It's great!" [laughs] They were on their way out, and we started working there. He moved his family in. He had a tennis court and a swimming pool built right away; it didn't have those two things. It had stables and all the goodies there. He had his pool table brought into the studio, so every now and then he'd shout back, "Billiard break! Pool break!" We'd go shoot some pool. He's eleven years older than I am, so we were kids! I don't think I was 25 yet, and he was 35. I think at the time he had four kids, and it's a great place for kids.

At that time, I was just his assistant. I never ever told him, but I took a cut in salary to go with him. I was doing okay for the time—it doesn't sound like very much money now, but at the time he thought he was being very generous with me and it's okay. What did I need money for anyway?

But it was still great fun, and I cleaned up strips and ran them into town and mailed them and sometimes filled in some blacks and we'd go over fan mail together. And he'd let me know...he got a fair amount of fan mail, he wasn't overwhelmed yet (Thank god, I would've become a typist! Actually, I was a pretty good typist.) But he'd tell me what he wanted to say and we'd personally answer all the mail that came in, and then we all socialized together too. We would go to the movies, and go out and run around—my wife and I belonged to a sports car club back there. I had the Corvette, Sparky got a little Thunderbird—I think it was about a '55 Thunderbird—and we would trade cars on weekends sometimes. My wife and I would take his little T-bird into San Francisco (it was only fifty miles away). On weekends we haunted San Francisco. He was an easy guy to be with; he's smart, he's kind.

In the last twenty years, I probably had half a dozen tabloids call me and say, "We found out you used to work for Schulz. We'll give you blah-blah money if you can give us some stuff on him." I'd say, "I can't give you anything! He's a really nice guy who doesn't do bad things. I don't know what's happened after I left, but when I was with him he was a super guy, and I don't think he's changed!" And they'd say "Just give us a little something and we'll put a little spin on it." And I'd say, "I can't do that!" [laughs] Why would you want to do that? It's like "I think I'll tear God down today,” y'know? You'd piss a lot of people off. But he just really was a good guy.

We came to California and I worked with him in California for a couple of years, and then in '60 moved up here, and I've been up here ever since.

I assume that the comic book stories you worked on, you wrote as well as drew them?

I'd write something and then we'd talk about it, and he'd bring me back into line with his thinking—which was fine, I was working for him—and I brought the stories out, and everything was generally okay, except he'd make corrections on Charlie Brown's head. The only person who can do Charlie Brown's head is Sparky.

Tough circle!

The magic of his thing is the simplicity, and the simpler something is, the harder it is to copy. If it's complicated, you can cheat. But you can't cheat with his stuff.

Jim Sasseville came out just a little later. I think Jim did do one book. Or part of a book, anyway. And then Sparky was starting another strip, can't think of the name of it. My memory, it's... forty years, a lot of things have happened. (Ed. Note: Dale is hardly alone in not remembering this strip. It's Only a Game ran in about 30 papers, Sunday only, and lasted only a year.)

Jim was really a good cartoonist. He was one of the four that used to hang around together. He was the best. He could do anything. He could do realistic; he could do all the stuff you'd like. Quiet, dedicated guy to his work: cartooning. And that's really all he wanted to do. He and Schulz worked on this thing together, and he was paying Jim... I think he was giving Jim a salary. Jim was fairly newly married. I think his wife put a little pressure on. Jim didn't care. He was just easy-going; as long as he was drawing, he was happy, but I think he said, "I'm drawing this strip and you're thinking of the ideas, I think we should split this fifty-fifty." Sparky didn't want to do it. Sparky, even then he was making good money. That was when we first got there, the first part of '58. But he was always very careful with his money. I don't know if it was he didn't want to do it or his wife didn't want to do it. And Jim said "Okay,” and he left. He went to San Francisco, and got a job I think doing illustration for some companies, the defense companies, I would imagine. I only saw him maybe twice after that.

You did most of the comic book stories, Jim did stuff, and supposedly Sparky did one himself.

I can't remember if he did the first one or not. He may have.

I've heard it said that he did the first one. There's one other people suspect that he worked on... I want to check that one out because I don't have a copy of that. Maybe he did the first one that was drawn but it wasn't the first one that came out. Sometimes these things come out in different order.

It could be.

The first one looked mostly like his style, but there's a few little things that made me go "hmmm, maybe not."

I wonder who ended up with that artwork! Doncha wonder?

I really do. If it were a multipage story, there'd be a lot of material there. Which brings me to the next point: this was before there was animation of the Peanuts or anything else that would be longer than four panels...

He didn't want any merchandising at all. That was before he was even doing any, any merchandising. He'd say "I'm not gonna do that." [laughs]

That apparently changed at some point.

That changed a lot.

In terms of storytelling, a four page or an eight-page strip is very different from four panels. What sort of adjustments did you have to make to do that?

That wasn't a problem for me. I think Sparky was just so used to doing his style that he didn't have to worry about it too much. If he had to write comic books, if Sparky had to write a ten-pager, he would've been able to do it. It would've been his style, and it would've said exactly what he wanted it to say. That's what he does; he's a creative guy.

Oh, he's a very capable guy. But for example, the comic book stories all have a fair amount of action in them. The strip tends to be very conversational, and if you drew that out for eight pages, that might not make a very exciting comic book.

I think one of the reasons we have more action in the comics is because the comic book people said, "We can't just have them standing there." In those days, they were able to dictate to Charles Schulz a little bit what they wanted, because to them he'd only been doing it for seven or eight years, and they felt they still could. Things have changed! [laughs]

So he said, "Okay, we'll get a little action in." It's so long ago, I forget every detail, but I do remember us talking about "it will be different.”

Obviously, when you were doing the comic book stories, a lot of your goal was to look like Schulz. Did you feel you had room to be yourself within that?

I didn't even try. I thought that I was working for him, and my challenge was to try to do it as close as I could to his stuff. I figured I had a lifetime to do my own stuff when the time was right. As long as it felt good, and was fun, I was going to do it! I really tried my best to do it as close as I could. And it wasn't always as close as I would have liked to have, because his style was... his style. I can copy other styles. But his style was the toughest of all.

Over the past couple of weeks [since the announcement of Sparky's medical troubles and retirement], we've seen a lot of drawn tributes to Schulz, and while they can capture the shapes, the line is impossible.

Not shaky enough!

It's not shaky enough for the modern ones, and there's a certain grace to the line on the older material that people can't really capture.

Well, when it does look right, you know that it's been scanned. Somebody just scanned it and slipped it into Photoshop and stuck it on the top of their drawing—which you can do now. A few years ago, nobody could do that. It'd be so easy now to do a Schulz comic book or a comic strip. You could just move things around and take this and that.

So he'd go over the comic stuff with you, after you were done.

We were young enough and our egos weren't out of control, either one of us. We were trying for the best product. I was trying to make him happy, and he was trying to make the comic book people happy.

How satisfied were you with the results?

All I could tell you is that I did the very best I could, for those days. Some people would say, "Well, you have to learn to." For instance, I was syndicated with Mirror Syndicate, and they asked me if I would ghost [laughs] Love Is... for 'em, because Kim's husband was... god, he was dying of testicle cancer, some gawdawful thing, and she was in no mood to draw the strip. So they asked me to do it, and I did it for a year. I gotta tell you: I really had a hard time drawing that poorly. [laughs] Y'know, I said, "Maybe if I draw it with my left hand, it'll look bad enough." It's not that my stuff is great, it's just...

It just that there's certain automatic corrections that you do.

Right.

I was writing and drawing it, and the money was good, so... [laughs] I just really did the best I could. So like I say, with Peanuts I came as close as I could and it seems that everybody seemed to be happy with it. As far as I know... if you know something I don't know, tell me! [laughs]

Oh, no, no. It was enjoyable stuff.

I'll have to take a look at those [gestures to a pile of Peanuts comics brought to the interview] I've got some stashed away somewhere, too. Not many.

This is far from a full set, but this is what I've got. Some of them are hard to find, and sometimes my wallet is less thick than I'd like it to be.

Are they getting pretty expensive?

If you want some of them in really nice condition, it's a thirty-dollar comic book, a fifty-dollar comic book. For a comic, that's a lot of money.

That's a lot of money.

Next time I go to a comic book convention, my guess is the prices of them will be up, because everybody's talking about Peanuts at this point.

I just talked to Sparky on Tuesday. I've had, in my lifetime a couple of the calls like that, from somebody's that's quite sick. It's like fifty-fifty that it's a goodbye call. I'm hoping that this wasn't a goodbye call. I'm really hoping it isn't. As soon as I heard he had it, I jumped on the computer and researched colon cancer. In all the research and everything that I see on it is "ehh-ehh"... it's really, it's fifty-fifty. It's not a death sentence.

I just wanted to give him hope—doing the strip is such an important part of his life. What I really wanted to say was "Sparky, you don't have to do a strip. If you feel better, when you feel better, you may want to draw two strips a week. You may want to do one a month to keep your hand in."

Well Jeannie, his wife, has been saying that she thinks that after he's better he might do what she called "comic book format" Which would make sense. You can have a book of a few pages of brand new material.

No deadlines. That would be good. It's such a part of his life; he really has to be drawing. And he should. That's his way of communicating. I hope that happens. I really hope that happens.

The covers [of the comic books] are all signed by him. Are they actually his drawings?

Yeah. Most of them probably are his.

You can get an idea of his style in those days by just turning around and looking up there [gestures towards the opposite wall, where three unfinished Peanuts strips are hanging. One is fully penciled. The other two seem to be there for single-panel experiments with tricky figures in ink.] Some of the stuff that he threw away at the time.

Wow.

And I just happened to pick 'em up, and I said, "You want these?" And he said, "Nah. Pitch 'em out or do whatever you want with 'em." I had a few more, and when I came to town, friends said, "You don't have a Schulz around or anything?" And I said, "Sure!" and I gave a couple of them away. And then one day I said, "I better keep these.” That's fun to look at.

Was there anything else you did in Sparky's studio?

That stuff was on the strips, like cleaning up a strip when he got done doing it, and filling in blacks. Folding them, packing them, taking them to the post office. But I really didn't do anything on his strips. Nobody believed it when he said, "No, I don't use assistants, at least on my strips." All the jealous cartoonists were saying, "Aw, bullshit, he's got cartoonists doing this for him." He didn't He did it himself. It's part of his life.

***

Dale Hale's work on the Peanuts stories ended when he moved away in 1960, landing in other hands (apparently including scripts by former Timely writer David Gantz.) Dell's Peanuts title came to an end in 1962, when Dell split with their printer-packager Western Publishing. Western took over all the comics rights and published the Gold Key comics line, which did not continue offering new issues of the Peanuts title. They did publish a few new Peanuts stories in Nancy & Sluggo and published a Peanuts series reprinting work done for Dell. The reprint series ran only four issues.

Dale followed up the interview with a phone call the next day. He explained that he did do one more Peanuts project after migrating from Northern to Southern California. In 1965, Sparky approached him with the text for a book based on a TV special that was in the works. He agreed to illustrate the book version of A Charlie Brown Christmas, and says his drawings were used as the basis for the animation.

Nat Gertler is the proprietor of AAUGH.com, an online source for Peanuts books and videos with a collector's guide for the Peanuts book fan. This interview owes much to the cooperation of Craig Shutt, Dr. Michael J. Vassallo, and of course Dale Hale (without whom it would have been much shorter.)

Life After Peanuts

After heading down to Southern California, Dale Hale faced frustration selling his own strip. With a baby on the way, he decided to try to find real money in the animation business. Starting as a technical assistant on the bizarrely animated Clutch Cargo, he quickly realized that the studios accorded more respect to writers than to artists. He moved his focused toward writing, while keeping his hand in art. Freelancing for a large number of studios, Dale's film work included such projects as Road Runner and Pink Panther theatrical shorts On TV, he worked on the animated Star Trek series, Tiny Toons, Shelley Duvall's Bedtime Stories, and many more.

He kept his hand in the comic strip field as well, helping the syndicates with such strips as Flintstones, Love Is... and Yogi Bear. His own strip, Figments, ran for fifteen years until he decided that stagnant sales meant that it was time for it to end. For eight years he did the panel You're Getting Closer for King Features. He also created a respected line of complaint cards, bringing the power of greeting cards to bear in expressing dissatisfaction of various sorts.

He considers himself retired now. It's not that he no longer works; he continues writing and drawing. It's just that he no longer has to do work, no longer needs to fill each day to keep bread on the table, and that seems to bring him some comfort. He is currently working on book illustrations, having recently completed some work for a German company that was generating 3-D animation from it. Dale's had some luck shopping around some live-action film scripts he's written. To take a break from art and writing, he performs musically with five bands. He has a pair of rare Morgan automobiles, and six tubas (which is at least five more than anyone really needs.)

His award-winning website, www.DaleHale.com,, showcases various projects (used and unused) that he has developed over the years. There you'll find drawings, comic strips, complaint cards, and even animation scripts in an all-ages environment.

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024