The Gods of Noon

Experiencing Egypt’s Pyramids in person, our correspondent comes to understand that 'In this wised-up, blandly cosmopolitan world, it's still possible for your travels to take you through a door.'

By Christopher HillI got back from Egypt—the only person I knew who had ever been to Egypt—and no one asked me about the Pyramids. My wife was too busy; the same with my co-workers. The extended family was strangely silent. My oldest friend did check in. We'd seen Lawrence of Arabia together in fourth grade, and he was excited that I'd finally gotten to ride a camel. But no one, not even my mother, asked me about the Pyramids.

People used to be fascinated by Egypt and the Pyramids.

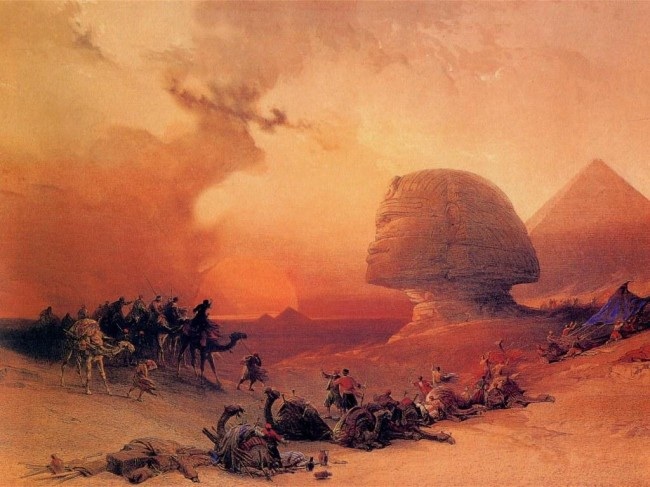

Back when Herodotus was wandering around the Mediterranean inventing history, people scarcely believed the Pyramids were real. To have seen them was to dine out for life. In the 19th century, after a visit to Egypt, you could regale the club with your tales as you sat by the fire with a whisky and soda. Just a generation or two ago, when the silver cigar tubes of the DC3s were carrying newly prosperous Yanks around the globe and Sinatra was singing "Come Fly With Me,” you could have gotten the whole block over to watch slides in the den, if you had done something as interesting as travel to Egypt.

In small towns in Illinois, boys would lie on the floor and look at the Pyramids in Richard Halliburton's Book of Marvels and think what a vast strange place the world was, and imagine a life big enough to take it all in. Egypt was still, as it had been for unthinkable stretches of time passed, the world's home of mystery. All this apparently changed sometime before I got there.

It occurred to me that maybe the Pyramids had become a sort of shorthand for the Absolute. Like walking on the moon or a night with Scarlett Johansen. Perhaps the question "What was it like?" is felt to be almost irreverent in its demand that you reduce the ineffable to mere words. You know, where do you begin?

Or maybe people feel that all they can do is nod knowingly when someone tells them they've seen the Pyramids, like when you see Hamlet for the first time and any one of the dozens of questions you want to ask, like "What was bothering the guy in black, anyway?" seem either too big or too simple, so you don't ask.

Maybe. But I suspect we've just lost our taste for it. Who needs a book of marvels when you have high definition TV? Today, high culture and low conspire together against adventure. In this day of the satiated imagination, cloyed with spectacle, the Pyramids are looking a little like a set on a Hollywood lot, a two-dimensional, rather hackneyed backdrop for some sort of post-modern King Tut Las Vegas playground. What once epitomized the unknown is now one more overexposed image in a lukewarm tide of images that rises around outcroppings of otherness like the Pyramids, until all you can see are the tops and eventually we forget how big they were.

They are very big. I've been to Egypt so I know.

In this wised-up, blandly cosmopolitan world, it's still possible for your travels to take you through a door. But when you come back through the door and you want to tell about the marvels that have changed you, the street where you live is so busy (Was it this busy before?), and the people in your house busier still, that you soon feel again the familiar dull urgency that drives people through their days in this world. And because this scenario is driven by fear, and because you're not without fear yourself, you slowly join back in, and little by little you forget. Until you become like the others who really don't believe there is such a place as Egypt, and are no longer curious about it.

So how would it be if I asked the questions myself?

***

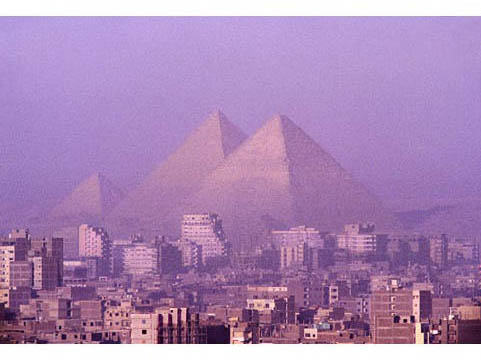

The Pyramid of Cheops takes up 13 acres of land and overlooks the neighboring pyramids belonging to the Pharoah’s son and grandson. Some 100,000 laborers worked roughly 20 years to build the Pyramid of Cheops.How does it feel to be in Egypt?

It takes a while to register. Driving in to Cairo from the airport at around 1 a.m. (when it seems all flights in Egypt arrive or depart) it looks initially as if you're approaching a sort of run-down Phoenix, Arizona. Lots of cracked concrete and palm trees. But before long you begin to get indicators.

What do you mean, indicators?

Well, for one thing, there's an awful lot of activity for one a.m. Muslims may be very religious but this, I soon understand, doesn't mean they don't party. It seems like there's a festival going on down a lot of the streets we pass by. As the crowds surge and sway, I wonder at first if we aren't watching the beginnings of some sort of civil unrest. But it's just a Cairo night. One of the people I'm travelling with, who has spent many years in the Middle East, says, "This is really the city that never sleeps."

Another indicator: Aziz, who came to meet us at the airport, is watching television. That would be unremarkable except that Aziz is also driving our car. He's got a small battery-powered black and white TV duct-taped to his dashboard so he can follow the Zamalek soccer team.

It's black and glossy as an ebony tabletop with an alabaster bowl of a moon set on its surface. The Nile is not mighty, like the Mississippi. It glides slow and muddy and slender in the moonlight. "A serpent of Old Nile." The river Shakespeare thought he knew. The river that shaped the oldest Egyptian dreams.Another indicator: We cross over a bridge and beneath us there's a river. Aziz says, "Nile." It's black and glossy as an ebony tabletop with an alabaster bowl of a moon set on its surface. We pass over the Nile, over to the island of Zamalek, in the middle of the Nile. The Nile is not mighty, like the Mississippi. It glides slow and muddy and slender in the moonlight. "A serpent of Old Nile." The river Shakespeare thought he knew. The river that shaped the oldest Egyptian dreams.

Later there were the cats.

Cats?

We've gotten into our rooms. I have passed through three continents to get here, I've been about thirty-eight hours en route, I have no idea what time it is for me, but I'm going to have a drink. I take a large gin and tonic onto a little patio outside the sliding glass doors of my room.

I'm happy to be in Egypt, happy to be at rest. I have the Traveler's Key to Sacred Egypt and I'm reading about gods, specifically Bastet, the cat goddess, and the ancient Egyptian veneration of cats. Thousands of mummified cats, I read, have been found in Egyptian tombs. That's when something sinuous crawls along my bare foot.

After my heart starts again, I find I'm looking down into the large golden eyes of a scrawny, dirty, feral cat. It slinks around the patio as if it belongs there, now joined by another. And another. Till there are perhaps a half a dozen cats on the patio, all variations of dirty white, dirty grey and dirty brown. There are more sets of reflecting eyes at the edge of the patio, just beyond the light.

When did you feel you were some place really different?

On my first day in Egypt.

In most of Cairo you are not in some timeless Middle East. Downtown Cairo hugs the east bank of the Nile for miles, and it is mostly of 19th and early 20th century provenance. It is built around the maidans—the wide, street-radiating plazas laid out by French planners and French-influenced Egyptians. It's interesting but not that interesting. The cultural heritage of Europe is something we absorb with our mother's milk. Washington D.C. is laid out on the same principles as the maidans of Cairo.

But that's not all of Cairo. On my first full day, Aziz takes me eastward, the car speeding over one of the monstrous traffic "fly-overs" built by Nasserite planners. (Let me tell you about Cairo traffic later.) We're going east from downtown Cairo, past where the maidans stop.

Other cities have places where downtown meets the neighborhoods—I think of the ramparts of Chicago rising hugely from the plain, and at their feet the flat miniature miles of neighborhoods merging into freightyards merging into suburbs, and then into prairie.

Here the transition is on a smaller scale but all the more dramatic. Because you're not just moving from downtown to neighborhood, you're moving from Europe, clinging thinly to the riverbank, into the Middle East; from the 19th and 20th century into the 15th; from straight, rational French boulevards to the labyrinthine city of Salah-al-Din.

There can be few better approaches for a newcomer to this part of the world. Cairo, going east from the river, starting in downtown, is set up like the holy-of-holies plan of an Egyptian temple. The further you go, the stranger things get. While we're still up on the fly-over I can see the change beginning. It's like being in H.G. Wells' time machine. As I look, history is played backwards and speeded up. The tall, western-style buildings along the river shrink, wear down, and are gradually replaced by buildings that take on desert color. The square windows lift up into pointed arches, the roofs into domes. Solid walls dissolve into mashrabiya—wood carved and perforated until it looks like lace.

‘I'm now in a world that is truly foreign to me, like no place I've ever been.’The transformation has a strange effect on me; a pulse of blood runs from temple to temple, lifting the top of my head just slightly, creating more space behind my eyes. I'm now in a world that is truly foreign to me, like no place I've ever been.

What was the old city like?

It is very dirty and very poor, very crowded and I'm not sure I belong here. But the old Not-Me is present, the first reward of travel. I follow a man bent over a large walking stick, through a network of alleys to the front of a huge mosque. I find later that this is Al Azhar, the great school of Sunni Islam.

Were you a little nervous?

I knew a woman once who loved to swim. She spent a summer waiting tables at a camp on an island eight miles off the coast of Maine. Each day she would swim from one island to a neighboring island, across a couple miles of open sea and ocean currents. I asked her if she wasn't scared. She said she didn't think the water would ever hurt her. I am feeling like that about Cairo. A stranger could get very lost in Islamic Cairo. But one of the disciplines of travel is throwing yourself on the mercy of strangeness. One usually (though not always) finds mercy. Islamic Cairo is intimidating to a Westerner at first, but this is in fact one of the safest cities in the world. Street crime is practically unknown here.

The streets are narrow and crowded, the buildings low and made of stone. Some are shops, some are homes. The interiors of the houses are very close to the street. I look to my left and into the dark eyes of a veiled old woman in black sitting just inside her doorway. Every so often a building raises itself up from it neighbors, decorated with mosaic-work and mashrabiya, one of the grand old homes from the age of the Mamelukes, the hereditary servants and warriors who became the masters of Egypt in the 13th century.

In downtown Cairo, almost everyone is in western dress. Here, no one I can see is. The men are all in gallabiyeh—the ankle-length white shirt—the woman all with head scarves, some veiled, many in traditional black. It's extraordinarily busy. Commerce is going on everywhere. There are animals in the streets, goats, chickens, donkeys. Donkeys carrying trays of bread.

I have left something behind and I'm glad. It's like losing your wallet and not caring. It's not so much home I've left behind, as a part of my self. A different me, always latent, usually dormant, has taken the wheel. There is almost nothing familiar here. Some men carry, on their shoulders, something like great silver samovars, filled with water that they dispense from a long slender spout into glass cups chased with silver. Women bake rounds of wonderful looking bread, inflated like popovers.

In between two streets there is an alleyway, covered by a big black awning, where there is a coffeehouse. I order a sort of milky lemonade. It's cold. It is very hot and dusty and bright on the street. It is very dark in the coffeehouse. I meet a young man who tells me he is in law school, and insists I go to the Faiyum Oasis, which sounds like Paradise or the Egyptian version of Cabo San Lucas. And they have plenty of hash. Would I like some hash?

Did you buy any?

No.

So tell me about the pyramids.

Not so fast. First you have to know about gods.

Go ahead.

You find gods in the Egyptian Museum. When Earth is finally invaded from outer space, our new masters may very well ask to see the Egyptian Museum first. It is one of the treasure houses of the planet, the world's greatest collection of Pharaonic art. I walk through it with Father John, a friend I have made, an Episcopal priest from Wisconsin. He is tall, skinny, sharp featured with a beak of a nose and eyes always half closed, so that seen from a distance, he looks to be in a perpetual doze. Close up, you can see that the expression is evaluative, examining in an unhurried way all that passes by. He is on the evangelical side of Episcopalianism. He is ascetic—he eats little, doesn't drink at all, walks great distances across the city without tiring. Looking at him now strolling through this strange opulence, it's easy to imagine him as a 19th century Anglican missionary, here to bring the Prayer Book and decent plumbing to the benighted Mussulman. I am enjoying his company because we disagree about almost everything.

We're passing through the Amarna Gallery, the art from the period of the heretic pharaoh Akhenaten, who abolished the worship of the old Egyptian gods in favor of exclusive devotion to the solar disk, the Aten, thus becoming, by some historians' reckoning, the father of monotheism. Amarna period art is known for a fresh naturalism in its portrayal of plants, animals and children. And also for its grotesque portrayal of the human figure, wide-hipped swollen-bellied hermaphroditic men, bodies stretched like taffy. Heads too are stretched and distorted, cheeks hollow, the jaw unnaturally big, the eyes pulled up at the corners like a face in a fun-house mirror.

As Father John stands looking at the giant head of Akhenaten—the epitome of the Amarna style—I notice a certain resemblance. There is something in Father John's long gauntness, the high cheekbones, the hooded slightly slanted eyes, that echoes Akhenaten. Perhaps they both feel the same way about the teeming multiplicity of Egyptian gods. Maybe the heretic pharaoh was not just the father of monotheists, but the precursor of all idol-smashing puritans. Father John looks thoughtful as we climb the stair to the Tutankhamun wing.

Inside King Tutankhamun’s tomb: ‘To encounter its entire contents all at once is overwhelming, a surfeit of glory.’The tomb of Tutankhamun—the treasure trove discovered by Howard Carter in 1922—represents the crown of the long, long history of Egyptian art, the height of Egypt's New Kingdom golden age. Interestingly, it followed the Amarna period by just a generation, but it represents a full restoration of traditional Egyptian splendor, along with all the old gods. Tutankhamun's tomb is the only intact, unplundered tomb of an Egyptian pharaoh ever discovered. To encounter its entire contents all at once is overwhelming, a surfeit of glory.

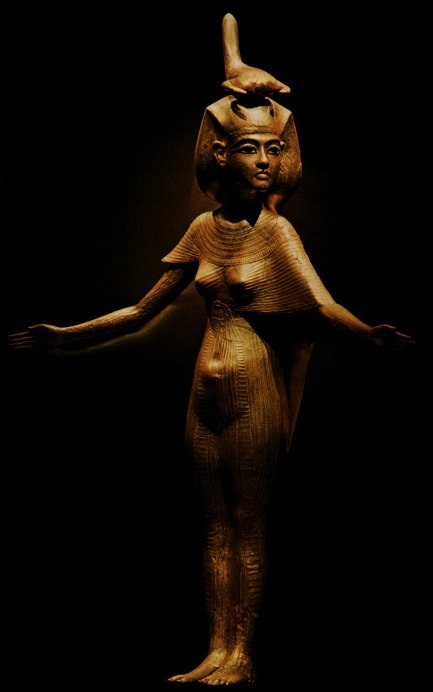

We come upon Tutankhamun's canopic shrine—huge gilded boxes within boxes that hold, in the central and smallest box, alabaster jars containing the king's organs. On each of the four sides of the outer box stands a goddess. The four of them—Isis, Nephthys, Selket, and Neith—stand guard, lovingly protecting the Pharoah's vitals. The goddesses are made of gilded wood, and they are some of the most beautiful objects you will ever see.

One key to Egyptian spirituality is that the ancient Egyptians believed that gods could be invited to come down and inhabit their statues. In other words, the sculpture was—at least from time to time—alive. Looking at the statue of Selket, you begin to understand the idea.

‘Her whole body is an emblem of the grace of Egypt: the breasts are small, shoulders slender, her form gently curving outwards to a rounded belly, and then down tapering legs to tiny feet. She is an ovoid, the body lithe as a fish. Her face is beautiful and remote, the face of the Egyptian peace, no expression but the expression of the sun.’She stands with arms lifted a little from her side. She seems to be presenting something which is beneath and inside her arms, reaching out and slightly down as if protecting or embracing things smaller than herself—a pose of benediction. You people the space between her arms and her body with phantom children. The poignant half turn of her head breaks out of the typical straightforward Egyptian gaze and gives her presence a life-like immediacy. Most Egyptian figures are impassive, scanning the far horizon. Selket seems to be responding to something in her immediate vicinity, but with an expression of imperturbable peace. She is called "She who breathes"—the Egyptians saw her as breathing life into the mouths of the dead. She guarded against venomous animals, and protected women in childbirth. Her whole body is an emblem of the grace of Egypt: the breasts are small, shoulders slender, her form gently curving outwards to a rounded belly, and then down tapering legs to tiny feet. She is an ovoid, the body lithe as a fish. Her face is beautiful and remote, the face of the Egyptian peace, no expression but the expression of the sun.

She teaches you about the nature of gods—her compassion is so human, yet the whole of her, the stillness and the sveltness, the poise, the vigilant tenderness of the expression, the richly signifying gesture—raises the compassion to a level that is more than human. She's a creature of a larger world.

I'm close to a realization about what is at the heart of the unending fascination of Egypt. And it's simple. People are drawn to Egyptian art because it makes them feel good. There is an immense ease that we faintly recognize, long lost, some natural property of the soul that tells of the grace that comes of knowing how to speak to the heart of life, the heart of the sun. There is a paradisal look and feel to Egyptian art. It's so relaxed—the "ancient Atlantean grace," as D.H. Lawrence said. It's not the least like medieval Christian art full of peril and sadness. Paradise was always close to the ancient peoples of the Middle East—not a disembodied home in the sky, but a garden, with water and shade and pleasure.

A voice breaks into my reverie. "All this... for death," someone behind me says. I look around. It's Father John. He's taking in Tutankhamen's dazzling storehouse—the golden faces, the fantastic animals, the gods and goddesses; a Protestant spirit stranded in the Egyptian Museum, kin to Akhenaten on one side, Oliver Cromwell on the other. Good Protestant spirit that bristles with distrust in the presence of kings and gold, excess and waste; stiff northern spirit here among all these lithe gold Egyptians with expressions like the sun.

Now can we get to the Pyramids?

Yes. Fire away.

Didn't they look smaller than you expected?

No. Bigger.

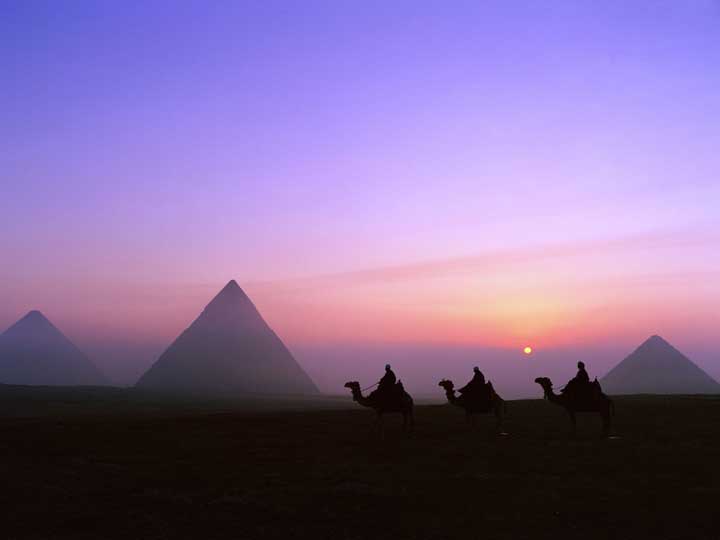

My first glimpse of them comes as we are driving out the Sharia al Ahram, Pyramid Road, from Cairo to a restaurant in Giza. This long avenue is, as everywhere, choked with traffic, lined with shops, markets, restaurants, carts, people. It is early evening, dusk, the Cairo smog making it duskier still.

"Well, Chris, there's the Pyramids," says one of my travelling companions. I look around but can't see anything that might be a pyramid in this crowded sidewalk scene. I say, "Where?"

"There, on the left," he says. "Up."

I still don't see anything. I look up like he told me to. Then the hair on my arms stands up. I have been focused on the activity in the foreground, looking for something in that scene. Now my focal point undergoes a wrenching shift. There is a vast shape behind everything I'm looking at, a shape that resolves itself into an impossibly big triangular silhouette in the gray-brown haze. The Great Pyramid of Cheops is not part of the scene I'm looking at, it contains it. It's the background to all of it, behind and above everything else, encompassing all the life going on in the foreground. It was too big for me to see. "Holy shit," I say.

The Great Pyramid of Cheops: ‘I’m as stunned as Herodotus. We are in the presence of something produced by entirely alien aspirations.’I'm as stunned as Herodotus. Humans will not see anything stranger until, however many centuries from now, our explorers walk the streets of non-human cities in distant solar systems. We are in the presence of something produced by entirely alien aspirations. The question comes to me as fresh and novel as it has to every other visitor to this antique land: "What is it for?"

Did you get any closer?

Yes. I was told to go early in the morning—less crowd, fewer hustlers. In fact I was told to be there at dawn, when the Pyramids are illuminated by the sun in the east. By the time I get out of the hotel the sun's risen, but only just. I grab a cab.

The taxi driver knows a good way to approach the Pyramid complex. He skips the main entrance by the Great Pyramid and gets into the streets of Mena village, up against the Giza Plateau. We come to a break in the low houses and shops, with a little parking lot. And suddenly there it is, golden, the Sphinx's head against the Pyramid of Menkaure, the identical color of the pyramid behind him, so the effect is of semi-transparency — a huge sand-colored ghost, a giant of sand gold in the morning light ushering human beings into the god-sized world behind him, the universe of the Giza Plateau.

So what's it like to see the Pyramids?

The way I would say it is that you're not so much seeing the Pyramids as being among the Pyramids. You're looking at them, of course, but it's not like regarding a piece of statuary. Up on the Giza Plateau you're on their turf, in their world, entering their geography and geometry. They are an environment, not an object.

Some feel dwarfed up here. Strangely, among these vast, spare objects, I think you start to feel bigger. It's as if you've emerged from the cramped world into the big world. Although you're tramping around covering some significant distances in the sand and quite hot, one's heavy self comes to seem, well, less of a factor. Sort of like your body is now just a membrane of skin buoyed along on the bright air up here. You are in a new relation or proportion to your surroundings. In contrast to the hugeness and weight of the few enormous objects around you, you are a rather light object. You feel unexpectedly comfortable in this gigantic environment. It may be a recollection of how things were when you were very young, and the dining room table was a huge, unarguable, fascinating fact. And like a child in the enormous Land of Adults, you have less existential anxiety. The Pyramids are a given. They are not malleable and contingent, as the world comes to seem more and more as we grow up. This is a liberating, rather than oppressive, sensation. You feel strangely at home in this new order of magnitude.

I begin to understand a little of the purpose of the Pyramids. The environment of the Giza plateau is meant to introduce you to a different scale of life. This place, with its orientation to stars and cardinal points, is a model of a bigger, universe-sized life, an attempt to bring the gods' perspective down to earth. To give a taste of the dimensions of eternity. Selket, in the Egyptian Museum, was instinct with a larger life. This, you realize, is the world that she implies.

Do you think the Pyramids were made by aliens?

No, but I think they might as well have been. What I mean is, the aliens who made the Pyramids were born right here on Earth. But they were no less alien than people that come from the sky. If we can't feel how different the Pyramids are from life as we ordinarily know it, then chances are we wouldn't be very impressed by extraterrestrials anyway.

The Pyramids are more than just the world's largest pile of stones. Out here among them, they are a primal fact—the first and greatest datum mankind offered up to the world. This is why cranks and crackpots down through the ages have addled their brains trying to derive meaning from the Pyramids. Because they mean something, because it's obvious to a child they mean something.

‘The Pyramids are more than just the world's largest pile of stones. Out here among them, they are a primal fact—the first and greatest datum mankind offered up to the world. This is why cranks and crackpots down through the ages have addled their brains trying to derive meaning from the Pyramids.’What did you do on your last day in Cairo?

I arranged to meet Father John at Fishawi's, a famous old coffee shop in the Khan el-Khalili. The Khan is Cairo's huge and intricate market, founded by the Emir Djaharks el-Khalili in the 14th century. Most of the Khan is made up of small shops in flagstoned alleyways, part of an ancient caravansary. This is the part of Cairo that Naguib Mahfouz, the Egyptian Nobel laureate, wrote about. Many of his novels are set in the Khan and surrounding neighborhoods, old middle class neighborhoods that flourished for generations but that have recently seen an exodus to the suburbs.

At every turn there is a new array of goods, ranks of gleaming brass work, silver and turquoise, glittering textiles. Some of the work on close inspection is obviously geared toward the hurried tourist grabbing souvenirs on his way to the airport. But many, perhaps most of the merchants are long established, with reputations to maintain. There is a market for gold work, a market for textiles, a market for herbs and spices, a market for perfume essences.

We find Fishawi's. One of the nicest things about travel is enjoying the indigenous arts of leisure that have been slowly perfected over the centuries. Egyptian coffeehouses are cousins to British pubs and French cafes. They're places to just be. To talk, puff on a sheeshah, read the paper, drink coffee or tea, play backgammon. The ease is the striking thing. In the West we harbor a fear that in ease—in not doing—identity will melt away. The coffeehouses of the Arab world are evidence that the house won't collapse if you're not holding it up.

Travel outside one's own cultural world poses the interesting question, "Who are you?" An interesting question, but not pressing. Not pressing, anyway, as we sit in the cul-de-sac of Fishawi's smoking Cleopatras and drinking thick sweet coffee, while the incense man waves his censer around. My priest friend and I look at each other. "This is nice," he says. I understand. We could stay here a long time. The Nilotic ease has finally gotten to Father John. A little area of Egyptian paradise, of the Atlantean grace here at Fishawi's.

‘Egypt is a place in the imagination as well as a place in Africa. It is simplemindedness to think that the two places—the country in Africa and the country in the imagination—can't both be true at once.’So why do you think that no one asked you about the Pyramids?

I think that all good travel has an inner and an outer aspect. Egypt is a place in the imagination as well as a place in Africa. The imaginary country grows from the real country; it's a counterpoint to it, a meditation upon it, a poem about it. If we didn't travel with an imaginary country in our heads, to synthesize what we see and hear, there'd be little point in going anywhere.

The relationship between the country in Africa and the country in the imagination is complex, more complicated than that one is simply real and the other simply not. It is simplemindedness to think that the two places—the country in Africa and the country in the imagination—can't both be true at once.

So maybe that's why no one asked about the Pyramids. Maybe they really wanted there to be an Egypt of wonders, and were afraid I might rob them of it with some knowing observation about how the Pyramids aren't as big as they look in pictures and the Cairo air is bad and the water makes you sick, and the Nile is narrow and dirty, and someone's always trying to hustle you.

The merchants in the Khan el Khalili today will sell a thousand more belly-dancing outfits and statues of gods. You could say it's pandering to the tourists, but I wouldn't. I would guess that some of those merchants feel that the Egypt of the imagination is as much their country as the street they live on.

Speaking of statues of the gods—before I left Egypt, I bought a replica of the statue of Selket. In thousands of homes around the world, statues of Egyptian gods and goddesses stand on bookshelves and end tables. They might seem like negligible things but even the bad ones offer up something of Egypt, if you choose to look for it.

Mine is not a great reproduction. Her arms are too long, almost comically long, and the unbalanced features are a mockery of Selket's beauty. But the gesture is still there. Sometimes at night as I'm turning out the lights I stop in front of the bookshelf where she stands. In the dark, the streetlight outside makes a pale gleam on her forehead and down her arms. And I think how, four thousand years older and six thousand miles away, there is a burning figure in a gallery in Egypt making the same gesture—that Egyptian blessing, weightless as sunlight, palpable as gold.

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024