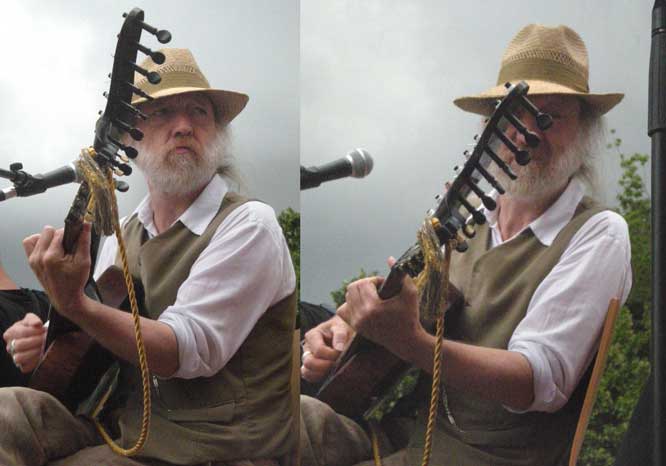

Roland Neuwirth: ‘God is Viennese. He has a soft spot for his countrymen and lets them into Heaven easily.’ (Photo: Karin Berger)I Feel Vienna

Roland Neuwirth In His Own Words

Exclusive to The Bluegrass Special.com

Ed. Note: When we launched our Border Crossings section two years ago, our first priority was an in-depth profile of the great Viennese traditional folk artist Roland Neuwirth. Finally, this month, our third anniversary, we have Roland in our pages, with no small thanks for this being so due to his good friend Gaby Sappington, a native of Vienna who has worked in the music business in both her native country--at Warner Music Austria her tireless promotion of Roland’s music was instrumental in two of his songs gaining extensive airplay--and in New York City, where she has lived and worked for the past two decades. Now Group Director, Marketing & Community Relations for the Metro New York chapter of the Make-A-Wish Foundation, Ms. Sappington remains defiantly and proudly Viennese and fiercely devoted to Roland Neuwirth’s music and to the man himself. She made the initial contact with him about this article; he took a look at what we do and agreed to a profile. I emailed him 17 questions, figuring we would begin an online dialogue; instead, he used the questions as a framework for writing an abridged autobiography/philosophical treatise/historical overview of his life and times and of the evolution of traditional Viennese music.

When we speak of Vienna’s music history, the names that spring to mind most easily are those of giants in the Classical world: in the late 1700s, Schubert, Strauss, Beethoven, Hayden, Brahms, Bruckner and Mahler made the city the cradle of Classical music; long before that, in 1498, Emperor Maximillian founded the Vienna Boys Choir. Less well known to the world at large is the richness of Vienna’s traditional folk music legacy, which centers on the pioneering work of the brothers Schrammel, Johann and Josef, in 1878, when they formed an ensemble with guitarist Anton Strohmayer to play their folk songs, marches and dance music for patrons in the city’s taverns and inns. In 1884 the trio became a quartet with the addition of clarinetist Georg Dänzer and billed itself as the “Schrammel Brothers Specialities Quartet (Specialitäten Quartett Gebrüder Schrammel) and became such a sensation that it was soon taking “Schrammel euphoria” to elite audiences in mansions and palaces not only in Austria but throughout Europe, and even, come 1893, to the International Exposition of Chicago. All the rage, and built on the foundation of some 200 songs and compositions the brothers composed in seven years’ time, Schrammelmusik devotees included the towering composers Johannes Brahms, Johann Strauss and Arnold Schönberg. In 1893, Johann Schrammel, only 43 years old, died; two years later, his younger brother Josef, then 43 himself, also died. Schrammelmusik lived on after them, though, and does so today, in its traditional form as the brothers defined it, and upgraded in a progressive form with appropriations from other European folk music styles.

Enter Roland Neuwirth with a whole new vision of Schrammelmusik. Besotted by American blues and R&B, his musical touchstones were, as he writes here, “Son House, Elmore James, John Lee Hooker, Blind Willie Mc Tell, Muddy Waters, Howling Wolf and Lightnin’ Hopkins. They were my daily companions. Jimi Hendrix and Johnny Winter were my buddies and Ray Charles my church.” But in his youth he was quickly disabused of any notion that he could be a black American bluesman from the South, yet still looked to push his music forward into new frontiers. A Vienna critic dubbed his band’s style “extremschrammeln,” a term Roland so agreed with that he adopted it as his group’s official name.

What follows is Roland Neuwirth’s own account--the first he’s ever penned--of his musical journey, which takes in his upbringing, his family life, the first stirrings of the passion still fueling his music, the history of Viennese music and even the state of his health--it’s all linked. Warm, funny, irreverent, cranky and soulful, Roland’s words are true to his personality and to his music, several examples of which are embedded below. He sings in his native tongue, but the energy and urgency of his performances transcend language barriers. If you can hear, you will understand. Our sincere thank you again to Gaby Sappington for making this happen and for her yeoman effort in translating Roland’s original manuscript. --David McGee

***

My Road To The Schrammeln…

I’m only partially a traditionalist. Yes, The Extremschrammeln play on traditional Schrammel instruments--otherwise we wouldn’t be Schrammels--but only rarely do we play “traditional“ music. We play my music. My score includes many other notes. And we sing ourselves. With the traditional quartets that was and still is not the case. In addition, we amplify our instruments. Even so, the starting point and basis remain the typical Viennese melodies and songs. After all, one’s got to be home and grounded somewhere, no? But Vienna shouldn’t stay stuck in the 19th century. There are still many places on the Viennese musical landscape that remain to be explored. My road to the Schrammeln was a long one that took many detours.

Allow me to explain and clarify a few basic and important points: The so-called “Schrammeln” are nothing more than a specific casting/grouping of instruments. Viennese music is also played in other formations, but the “Schrammel“ casting/grouping is considered the créme de la créme, a little luxury. It consists of first and second violin, a clarinet (tuned in high G) or a chromatic button accordion (tuned in Bb) and a double-necked guitar, the “contra-guitar.”

The last two instruments are a uniquely Viennese invention. They have a very unique, special sound. The Viennese accordion, called a Knoepferl is a piece of genius. The buttons are arranged in three rows. The notes are arranged in a zick-zack, so that the distances between octaves take up less space. This way, the right hand can easily traverse over three octaves. That’s how this seemingly small instrument achieves a considerably greater volume of tone than all other accordions, excluding the bandoneon. It’s made of wood, the buttons are mother of pearl (not plastic!) and the tuning stocks are placed on soft leather. The sound of the instrument is accordingly soft and velvety. To call our beautiful Knoepferl an accordion is almost an insult. At least she should be called a “concertina.“ If said instrument is made by an expert, then she needs to respectfully be addressed using the name of whoever made it, “Budowitzer,” “Frimmel“ or “Kuritka.“

The contra-guitar also comes from the workshops of old, traditional Viennese guitar craftsmen. She features not only the standard six-string guitar neck with the usual fingerboard, but in addition a second neck with seven to nine bass strings without frets that don’t need to be held down, since they’re already tuned in half steps--to be precise, from Eb-A, Ab or G down. The older instruments still feature a “Steckwirbel“ (the little pins used for tuning) made of ebony (like a cello). Everything about this instrument is of the finest quality. The back of the body is not made of two parts but made from one piece of maple wood --how big trees still must have been back in those days! The owner/player of a regular contra guitar is very proud of his 15-string “Resinger“ (again, name of the maker), the lucky ones own a “Wesely,” and you consider yourself in seventh heaven if you can call functioning pieces from masters Swosil, Angerer or maybe even Scherzer your own. Those guitars have an incredible tone/sound. That I put pickups on these pieces seems to some like mixing a 1940 Mouton Rothschild with strawberry syrup: Sheer ignorance. Upstart, nouveaux riches snobbism. My snobbism goes even further. I don’t play on just any strings, but on my own. They’re called “Vienna Sound“ (Neuwirth Custom) and have been created/designed with my input by the oldest Viennese string factory. My colleagues are green with envy.

In Munich and the former Eastern Germany there have been other attempts to build Schrammel guitars, but they just don’t sound the way they’re supposed to. In my view they don’t belong there, anyway. Schrammel music belongs to Vienna.

In 1878 the two brother violinists Joseph and Johann Schrammel, together with guitarist Anton Strohmayer, formed a trio that shortly thereafter was expanded to a quartet with clarinet virtuoso Georg Dänzer. The grouping of two violinists, clarinet and guitar was not their innovation. This and other, similar groupings had been in existence for a long time. But the Schrammel brothers were virtuoso, academically trained violinists. In folk music that was something extraordinary, far from the norm. They composed hundreds of marches, dances and waltzes, wrote fantastic arrangements, dug out old Viennese waltzes and thus preserved them for future generations. Titles such as “Weaner Gmueath“ (“The Viennese Soul”) or “Wien bleibt Wien“ (“Vienna Remains Vienna”) have become evergreens. The brothers became so successful and popular that their last name became the name for the instrumental grouping of their quartet. Everyone now wanted to play Schrammel. Schrammel quartets popped up everywhere. The soft sound of the button concertina asserted itself against the high clarinet and is today, with the clarinet, part of the current grouping/composition/casting.

The clarinetist Dänzer played in 1893 in Chicago on the occasion of the World Exhibit. He passed away on the ship on his return trip. Having no appropriate replacement for him the brothers Schrammel exchanged the clarinet for the concertina in their lineup.

The original Schrammel Quartet, 1890: (from left) Josef Schrammel, Johann Schrammel, Georg Dänzer, Anton Strohmayer. ‘Everyone wanted to play Schrammel.’

Wien bleibt Wien (‘Vienna Remains Vienna’), composition by Johann Schrammel.One year before I was born, my father owned a self-made marionette puppet theatre. His performances took place in various cinema halls. Although the puppet theatre was quite successful, he stopped it at the moment of my birth. He began to work in a Bakelite factory for a living. What a pity! I’m sure I wouldn’t have had anything against the puppets. But now my poor daddy turned himself into a puppet on a string. For only half an hour per day he remained an artist. During lunch break, he came home to paint a little. I sat under the easel, the smell of oil paints in my nose, and watched him while he was painting in his white and dusty factory work clothes.

We lived on the outskirts of town in a worker’s district near the always-gray Danube. I grew up in quite desolate surroundings and amongst people ruined by the recently ended World War II. Once I saw a large puddle of blood in front of a door in the neighborhood and with it the broken glass of the small roof overhead--traces of suicide. Every day the blood spot turned a bit paler. A few days later the roof was repaired. The bloodspot vanished. I was five or six years old, but even at that early age I became aware of how little remains of anyone’s life. This had a deep influence on me, and my songs, too. Later, I wrote songs with titles like “Simply Gone And Away” (“Afoch ganga, afoch weg”) or the music to the lyrics written by Peter Ahorner for “Time Is Such A Crook/Scoundrel” (“Die Zeit is a Gauner”). Another song, which is a bit more comforting because of its humor, is nothing more than a list of all the Viennese words for death and dying, just like this: “He threw himself into the wooden pajama” or “he put up his boots”--all very descriptive and somewhat logical images of passing away.

It’s kind of strange. If one hears that someone passed away, one tends to react with shock. “Oh my God! The poor guy! What happened?“ In Vienna, we say “My condolences“ and add: “Oh well, that’s that. Now he/she is at rest.“

Even in the classic, traditional Viennese songs from around 1860 there was (almost) always a last verse that dealt with death. Or at least with heaven and God. But it’s a children’s book heaven. God is of course Viennese. He has a soft spot for his countrymen and lets them into Heaven easily. Once there, the Schrammeln sit with wine, poured by the angels, and play with all the great ones of whom the Viennese are so proud. In heaven, they all continue drinking just like they did on earth, but it’s so much better and more beautiful. One doesn’t have to work any longer; the Viennese just wants to be blissful/overjoyed/happy. That’s how it’s remained ever since the days of the emperor, when the Viennese was still so proud of himself and full of confidence. He wore a derby hat, twirled his moustache and sported a silver pocket watch chain.

It’s been a long time since Austria was an empire. What remains is a tiny land. But we’re like a torso with phantom pains; the emperor is still somewhere, somehow in our bones. The Viennese wants to be someone. Even in death. That’s why he affords himself a “schoene Leich.” “What the hell is aine schoene Laich?!“ you might ask. Well, it’s a fanciful funeral with marble stones, a beautiful casket carrier, many honoring/flattering speeches, live music and at least eight “Pompfeneberern“ (pallbearers) and 100 guests. One might not have lived in luxury, but at least one died in style. In Vienna, the cemetery is filled with life. (Best of all is of course the tomb of honor. It includes anything your heart could desire and is paid for by the city government).

Even as a young boy I thought a lot about death. I was spooked by the dark and the covered coffin. The entire religious (Catholic) ritual with all its scents and the thought of helplessly being locked in a hole in the ground. The poor surroundings of my childhood, the musty smells and the leaden gray of the houses, the basement filled with rats, all that had something to do with my fixation on death.

Roland Neuwirth, liveObviously this atmosphere was so dominant that it had to have an impact. It marked me and my brother, who’s two years younger. Our imagination was triggered in the strangest ways. He had to go to a day nursery, a dark shambles in a basement, and I went to kindergarten, which was a wooden barracks. At the end of each week, the caretaker had us line up in front of her. The girls would get a gentle touch on the cheek and the boys were slapped in the face. The girls then had to drop a curtsy and the boys had to bow. My mom told me that she once asked how I was doing, and was told, “He doesn’t really talk much, but he bows in a well behaved manner.“ My most treasured present was a mouth organ. It was called “the good companion.” I carried it with me at all times.

Weather permitting it was off to the Danube. She wasn’t yet regulated in those days and her banks were vast, covered with wild bushes and willows. The bombs of war had left deep holes. After some flooding, they formed into small pools. Us kids roamed about. At the side of one such pool stood a man with a string in his hand, on which a wooden brush was fastened. He threw it into the water. Soon all kinds of frogs sat on top of it. That’s when he pulled the brush with the frogs to the shore, opened a pocketknife and started slicing the frogs. When one of us asked what he was doing, he replied, “I’m the frog-slicer from Floridsdorf.” [Floridsdorf is a district in Vienna.] At night I had bad dreams. Still, at the age of 15, I woke up, gasping for air. Maybe I was too sensitive. I even stuttered for a while. Other than that I didn’t display any big problems. All and everything passed.

‘Around 1950, Vienna Had Become More Morbid and Ludicrous’

Around 1950, Vienna had become generally more morbid and ludicrous. The author H.C. Artmann with his book “med ana schwoazzn dintn” (With Black Ink) and the Expressionists definitely contributed to that vibe. They reflected the mood of my childhood days. Not only simple folks, but intellectuals, too, now wrote song lyrics in Viennese dialect. All of a sudden there were Viennese songs that not only celebrated themselves but also were sarcastic, mean and self-critical. The black abyss of the Viennese soul was revealed and celebrated in song, along with St. Stephen’s Cathedral, the Danube and the Riesenrad (the big, famous Ferris Wheel immortalized in The Third Man). At times with really good poetry.

My mom was a teacher. At first she taught religion. Then she received therapeutic training and taught at a school for children with disabilities. My first school years were spent there. Although I was “healthy,” since nobody else was there to take care of me, my mom took me with her and invented some kind of handicap so I could go to her school. To this day I can’t explain to myself why our parents weren’t more concerned about our psyches: They were severe and impatient; often their hands slipped to hit us. I assume they were overwhelmed. Still, there was lots of heart and caring. Our artistic impulses were always praised, albeit never seriously encouraged.

When I was seven we moved to the district of Hernals. I still live there. A beautiful district! We moved into a new building, on a chestnut-lined street, with a view of sunny vineyards on the small crests. My father had managed to improve our lives. He worked as a tourist guide and then as a restorer at the Schoenbrunn castle. He restored the imperial carriages. For him, as a painter and sculptor, this was a true ascension. Hernals is the cradle of the original Schrammel music. This is where the brothers Schrammel lived up until their death and it’s where they’re buried. Their guitar player Anton Strohmahyer survived all his fellow musicians and lived to be almost 90. He led two other quartets and died right before the beginning of World War II. His last apartment is on my street, right across from mine, even on the same floor. I can see his windows. When we moved here, I had no idea about Schrammel music. Now I make my living with Schrammel music and once lived quasi side-by-side with this legendary colleague. Wonder if that’s all pure coincidence?

The family also afforded itself a summer cottage on the Danube. We had it for about ten years. That was the best time of my youth. A paradise. My brother and I lived like Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, every day out in the wilderness. We fished, bathed in the river, and the paddle steamers made fantastic waves. We fell asleep to the sound of frogs or the raindrops falling on the tin roof. Today a power plant has brought the water to a standstill and cut off the Danube, our main artery. Such experiences stay with you. I’m a passionate fisherman. I’m drawn to the wilderness. Even if there’s little--or no--time for it, I’m of the opinion that one always should carry his fishing license. A life without a fishing license is only half a life, I’d say.

Roland Neuwirth & Extremschrammeln, ‘Stiang steing,’ February 10, 2010

At the age of 13, I discovered a guitar in our linen closet. My father showed me three chords that he knew. Step by step I taught myself some tricks. At age 15, I played at a teenage party in the “Prater“ (a famous Viennese amusement park). The owner of a merry-go-round had hired me. Behind the merry-go-round there was a terrace. It was like in the Stone Age. I couldn’t afford an electric guitar. So I mounted a pickup on a beat-up guitar. An old radio transmitter served as an amplifier and a curtain rod as a microphone stand. With this prehistoric equipment I entertained an entire community, together with a drummer who showed up unannounced.

My first band didn’t get past “Hey Mama, keep your big mouth shut!“ and “House in The Country.” It consisted of apprentices of the graphic trade. I was training to become a typesetter. “Being a musician is not a proper or safe profession,“ my parents warned me. “Learn something safe: typesetting!“ (The only thing safe and secure about that job is that it’s become extinct by now. My unsafe profession of being a musician I have, however, pursued for 36 years). Back then I saved money to buy a pink colored electric guitar. She was my pride and soul. In an instrument rental store I found a contra bass. There were a couple of them lying around. In the adjoining room a guy tried out a set of drums. I picked up the bass and noticed that it was tuned like a guitar. Even the first notes rolled off my hands easily. I tried to swing along with the drummer who then came over and winked/nodded at me. It was like a confirmation that I picked the right instrument. I paid the monthly rent for the instrument and took the case with me. My parents were in shock. Where to put it? The small room that I shared with my brother was already filled with paintings and an easel. I don’t remember how, but in the end a solution was found. The next day, as I approached our entry, I heard strange sounds coming out from our apartment above. As I entered, I found my father sitting on the toilet seat blowing into a gigantic tuba. He had gotten inspired to also rent an instrument and, since there was no room to practice in our place, chose the bathroom as rehearsal space. I loved him for that.

We attended Swing and Dixie evenings. One of the groups was looking for a bass player, so I jumped in. It was by no means a professional band but we played with enthusiasm. From now on I went everywhere with my bass on my back. After a night at a club I carried the case home for miles on foot, tied with a string to my back. I always had bloody blisters on my fingers. I slipped unnoticed into the room where my parents slept to take a needle from the sewing kit and prick open the blisters. Although I moved quietly like an American Indian, the heavy odor of beer and smoke that I carried with me woke my parents each and every time.

Along with the Dixieland bands, a truly original guy and intellectual named Franzi Bilik performed on and off again. He had fun turning old standards into Viennese satire. That’s how “I’m gonna sit right down and write myself a letter,” thanks to his satirical word play, turned into the phonetically similar Viennese “A int´ressanter Job is Bombenattentäter“ (“an interesting job is to be a bomb terrorist”). Bilik was the first Viennese singer-songwriter. He played the violin and guitar. Together with a friend from our Swing & Dixie band, we started a Viennese trio and called ourselves Brogressiv-Schrammeln. This was meant to poke fun at the designation of “progressive” (a very cool word at the time) then given to all songs that weren’t mainstream, and to make fun of some of the self-declared artistes of that era who claimed they were “progressive“ because they played “funk.” Critical songs at that time were called “protest songs" and the people performing them, along with all long-haired folks, were called protestler-–all very provincial, when it came down to it.

This trio had nothing to do with Schrammel musik. The name was misleading. We were terrorists. One day, a senior citizens club invited us to play. Those poor old people almost had a heart attack when they heard what we did to their beloved Viennese songs. We had it in for those horribly kitschy and mendacious songs in which those retired people sought refuge in the form of denial. Ever since the ‘50s, Viennese songs have decayed and become corrupted to meaningless, schmaltzy old people’s whining. It’s important to state that the fans of such songs were often the exact same people who called us young ones names such as “hippies“ or “Rasputin” on the street and recommended we be sent to work camps. (No exaggeration.) We might have looked like hippies, but were normal, working people. Some of us were beat up or were held up while our hair was cut off. When we rehearsed--even in a soundproofed basement--they sent the police after us. There wasn’t a single day in which we weren’t harassed. In that time we certainly got to know the famous “golden Viennese heart“ that’s sung about in those schmaltzy songs!

The job at the printing shop became more and more frustrating. I didn’t see any future and was always tired in the morning from the long night before. After one of the sessions in the club I shared my frustration with a blues guitarist. He had a Hungarian Roma (gypsy) background, was considerably younger than me, independent, and lived solely for his guitar. He played fantastically. I on the other hand was married and had two kids to take care of. He said, “Why don’t you come join us at the music academy?” I was completely perplexed. This young guy was classically trained! I stuttered, “But I don’t have a high school degree and cannot read sheet music.” “Doesn’t matter,” he said, “all you have to do is pass the entry exam. If you practice for nine hours daily, you can take the exam. The exam is in three months.” “But how am I supposed to do this?” I asked, “I’ve got to go to work every day, plus I’m already 23 years old!” He answered, “Then you’ll have to practice at night. I’ll teach you twice a week; you practice all scales, one etude and one old master. I’ll be relentless.”

Roland Neuwirth & Extremschrammeln, ‘Wien wieda amoi gspiern,’ live, February 10, 2010I practiced until my fingers bled. I realized that this was my only chance. Three months later I appeared at the exam and was actually accepted. I felt as if I’d gone from hell to heaven. That friend saved my life. His own life he threw away a few years later. He overdosed on heroin, not yet even 30.

I didn’t become a Segovia. But at least my musical horizon expanded. I had other plans, anyway. I wanted to write. Already in 1974, at the start of my studies, I founded the Neuwirth-Schrammeln. They’ve been around now for 36 long years and still exist, as I’ve turned 60 by now and am a Methuselah. Back then I was 24, as I started to get engaged in our own folk music. The Viennese played all kinds of music, not just their own. Schrammel music? In the hippie days that was complete nonsense and craziness. We sported shoulder-length hair and long beards that reached to the belly. The way we were dressed--in ragged outfits--one would have expected Jimi Hendrix music. Instead we started up the sound of those sweet violins. People scratched their heads; some of them laughed--that’s how silly and sick this all seemed to them. It didn’t seem to cross their minds that maybe they were the sick ones.

Our Schrammeln were a small sensation and we got written up in all the newspapers. The entire idea hadn’t even been mine. It was my father’s. He had taken notice of my identity crisis. I had wanted to be a black blues guy so badly, one from the Mississippi Delta, or at least from Chicago. Even when it rained I wore black sunglasses. In clubs I played on my dobro in a self-taught bottleneck-style and sang in an English that not even I understood. I had learned it from the old blues records, the way a small child imitates the sounds of her mother.

One night, there were American guests at the club. They asked which Southern accent I had and my fellow musicians broke out in hysterical laughter. I, or course, felt very flattered that Americans, whom I admired so much, would consider me to be one of them. Or did they?

Ray Charles, ‘Georgia On My Mind.’ Roland Neuwirth: ‘Ray Charles was my church.’My idols were Son House, Elmore James, John Lee Hooker, Blind Willie Mc Tell, Muddy Waters, Howling Wolf and Lightnin’ Hopkins (in that order). They were my daily companions. Jimi Hendrix and Johnny Winter were my buddies and Ray Charles my church. Jimi Hendrix I even got to see live when I was 16 years old! Afterwards, I was tone-deaf for three full days. At 17, I seriously considered emigrating. I’m sure that if I had followed through on that idea I probably would have remorsefully returned soon after. But maybe I would have learned the language at least. Either way, my worldview crumbled and my mirror image flickered.

I took off the sunglasses. What I saw in the mirror wasn’t the cool blues man from Louisiana. I cursed my lack of school education, my job as a typesetter and all of Austria. At the same time, I started to re-create it for myself, to maybe at some point own it, this Austria, this Vienna. I dug around in the city’s musical archives. I worked my way through huge mountains of kitschy songs to discover and unearth the gems and precious ones.

One day I came across a crazy collector. He collected historic blues and Viennese song recordings. When I first heard the brothers Mikulas on shellac, my heart stopped. Their version of the “Schnofler-Tanz” infected me for forever with the Schrammel bacillus. It was the way the violins were played. The beginning celebrates the theme like a sanctuary.

The “ponte-cello” played parts are played in such a laid back way that it doesn’t get any more modern and the final sequences have a breathtaking tempo. It literally lifts you off your chair.

Please note: In my view, Viennese dances are not for dancing, but for listening only! Viennese marches are the same. There is no way to march to them, because of the many varied tempos. If you insist on marching, you have to be drunk.

It’s a subtle and at the same time austere, sharp music, just like the taste of Viennese wine. I own this record. The label is from the Emperor’s days and therefore in three languages (Hungarian, Czech and Viennese); and Americans have printed the title—incorrectly--as “Schnoffler-Tanz.” It’s a gem! From this listening experience, from the roots, I had to find my way into the present

Only few people know that we owe these old shellac recordings to America. The old labels had taken it upon themselves to travel the world to discover authentic music. Those are invaluable documents. Many of them rot in various flea markets. That’s how it is here with us.

I wrote obsessively. There was enough material. The music had to come at the same time as the chorus line in order for my songs to be accepted by me as a song. They had to be a symbiosis of text and music. It was a great exercise to use the tram rides to improve my tonal imagination by scribbling melody sketches on little scraps of paper on the tram and then, back at home, test them on the instrument.

The lyrics were mainly socio-critical, definitely provocative and contemporary. In the meantime, “Austropop” came into being. The “dialect-wave,” as it was called, featured similar themes. Texts in Viennese dialect were quite common in the ‘70s. But in the ‘80s, our own language all of a sudden was no longer “in.” German dominated the market. In the late ‘80s English increasingly became the language of choice for Austrian popular music, until it finally dominated. By then I had found my own true identity with and through the Schrammeln and considered the development of Austrian musicians all singing in English self-denial. I wrote the satire “Hunds” (“Dogs”) in response to the popular musical Cats. The poster showed a bleary-eyed dog’s eyes instead of the noble cat’s eyes. In conjunction, I created the depiction of the reverse development of Homo Sapiens to Homo Vindobonensis [Latin word for Viennese], a dachshund mutt with an arched backbone: The Viennese has lost his spine and fallen back on his four legs.

In The Beginning, Our Performances Were Open Confrontations

‘…a journalist called us ‘Extrem-Schrammeln.’ The name fit and we embraced it. At least now everyone knew right away that they wouldn’t get the traditional Schrammel music from us.’ Photo: Wolfgang H. Wögerer, Wien.In the beginning, our performances were open confrontations. I jumped off stage and started arguing with people who continued chatting during soft songs or instrumental pieces. We geared up. The violins were equipped with pickups and the concertina roared through the amps. The drums and the bass flattened people to the wall. And then showed them the door. Instead of inviting people in with our music we threw them out. I heard a woman say, “This guy is ruining his career.” We had recorded an album that we called “extreme” and that’s exactly what it was. Good old Viennese dances became--when electronically amplified--quite interesting and powerful pieces. They grooved in a ¾ beat--something new in those times of monoculture that knew only 4/4 rhythm. These were exactly the dances that we had found on the shellacs.

During a TV performance of the Rock-Schrammeln, a journalist called us “Extrem-Schrammeln.” The name fit and we embraced it. At least now everyone knew right away that they wouldn’t get the traditional Schrammel music from us. But the violinists started to revolt. They didn’t want to play in a band that never featured a true piano. I got that. The crunched sound served its purpose for a while as a statement, but creating multi-faceted music with it was impossible. At that time, technology wasn’t advanced enough to enhance acoustical instruments in optimum quality. We weren’t musicians--we were warriors, even with each other. One of my violinists was so unreliable that we constantly fought. I became more and more stressed and nervous. A thyroid malfunction was diagnosed and I lost more and more weight, sweated profusely and trembled. I looked like a skeleton. A doctor said that unless I went to the hospital right away I’d be dead in two weeks. Dying at 30? I agreed to surgery. The vocal chords were quite damaged from the surgery and for months I went to therapies until the voice slowly strengthened.

For half of my life I’ve now taken medication. At the beginning the doses were off. I was prescribed too much but didn’t know that. My heart palpitations were off and I had severe panic attacks. In the middle of the night I’d run around, convinced that I would die if I were to stand still or stop. Hours later, my wife would pick me up somewhere in the city and drag me home. She attributed my state to the fact that I didn’t take good enough care of my body and only sat in my smoky room, composing. She argued that a house in the country would be better for me. I was sure I was going crazy. Since my songs brought in enough money, we bought an old farmhouse. It all happened in a flash. As soon as we had the house (and the workload that comes along with it), the doctors finally found the right doses for my medications and I felt healthy. Now I was stuck with this house that I didn’t really want. But my wife was happy. No amount of wild horses will drag her away from there. Together, we have a wonderful son who’s right now studying in Switzerland.

We turned our backs on bass and drums. We still amplified our instruments, but in a much better way. I limited myself to playing the contra-guitar and left the Fender in the case. With the new singer Dorli Windhager, increasingly professional violinists and ambitious arrangements, we finally approached real music.

At this point it should be said that my signature is well known, since the arrangement is already woven into the composition. It’s an essential part of it. It’s important to me how the harmonies run. In the end, each crossing has to sound as if this music had existed for forever. Only then can each musician find the free space they’re naturally looking for, without the music losing its character. Reciprocity ensues. My violinist Manfred Kammerhuber has been writing wonderful dances and waltzes for some time now. These are genius and I think they’ll remain as authentic Viennese gems.

That’s why I don’t like to perform solo. My songs are meant for the Schrammeln. And I want to harvest together with them. I’m happy that I can harvest. And the next sowing will be a new experiment.

Roland Neuwirth & Extremschrammeln in the documentary Herzausreisser.A band develops, and with it the quality of the music. We kept the name Extremschrammeln. I wanted to change it but the record company advised against it. We were too well known with this name. Whatever. Names are meaningless. My name is Neuwirth and I’m neither new (Neu) nor an innkeeper (Wirt). But I’ve gained the wink of the eye. I’ve become Viennese.

Two of my musicians have been with me for decades and others were and will be, God willing. Our manager, Andreas Koepp, has also worked with us for forever, exclusively.

Around 1980, I received an assignment to write a piece for Schrammel quartet and an orchestra. It premiered at the Wiener Musikverein, a Classical venue. This was followed by a few new orchestra waltzes that premiered at the Brucknerhaus, named after Classical composer Bruckner. I also took on some film and theater music assignments.

We toured Europe. In 1999 we embarked on a U.S./Canadian tour. In places such as Seattle, Los Angeles and San Diego I met “Old Vienna”--original Viennese-born people who had emigrated! Gaby Kopinits, my unshakable/stolid New York connection, assisted me as well. But still I remain loath to travel. I had to almost be dragged to the ensuing dates in Cap Verde and was able to avoid some other tours.

Authentic language requires authentic music. Austropop had to disintegrate, since it didn’t have its own music. It always tried to imitate what came from America. That’s how you could make money. I also once let myself be talked into a pop production of my songs. Warner Music Austria spent a lot of money on it. Thanks to the efforts of my dear friend Gaby, who by now has been living in New York for over 20 years, two of those songs even did quite well at radio. She did a lot for me. But I was never really happy with that music. She knew that and also how badly Austrian radio can treat its local musicians. It’s been a while that you can hear Austrian artists on Austrian radio. “Radio Vienna” broadcasts all kinds of music, but no Viennese music. I wonder what kind of country ignores its own homegrown music?

Yet miracles happen. In the past few years I’ve recorded a live CD with the ORF Rundfunk Orchestra, the government-owned radio orchestra, and even performed a Schrammel Operetta--a complete novelty--with great success and to critical acclaim.

If you’ve walked for a while, you turn around and look back. I’ve written more than 300 songs. Some of the most successful ones we recently recorded live on a DVD. The names of my musicians are: Doris Windhager, Überstimme (vocals); Manfred Kammerhofer, 1. Geige (first violin); Bernie Mallinger od. Igi Jenner, 2. Geige (second violin); Marko Zivadinovic, Knöpferl-Harmonika (button accordion--concertina).

We have released 15 recordings. The Austrian fans remain intensely loyal. For whatever it’s worth, the Extremschrammeln succeeded in getting more and more young people interested in Viennese music. By now, there exist a considerable number of copycat ensembles.

Roland at rest: ‘May I quote from the old Romans? ‘Nun quam est qui ubique est!’--He who is everywhere is nowhere! I’m definitely here.’ Photo: Wolfgang H. Wögerer, Wien.Overall, I’m most happy being home. Here my language is understood. It might or will most likely be extinct in 10 years, but it’s the only language I have. Maybe one becomes an artist only when one has no other opportunities or outlets.

I don’t really feel restricted. Language is like the music to which it belongs. The small space that I have at my disposal becomes larger the more I become engrossed in it and discover new spaces.

May I quote from the old Romans? “Nun quam est qui ubique est!“--He who is everywhere is nowhere! I’m definitely here. And should you some day be in Vienna by any chance, come visit me. It would be my pleasure.

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024