The Perkins Brothers Band: (from left) Clayton Perkins, Carl Perkins, W.S. Holland, Jay PerkinsWhen Carl Perkins Discovered Bill Monroe’s Music

By David McGee

In 1939, Carl Perkins was approaching his seventh birthday, and his first year of learning to play the guitar. The entire Perkins family worked the cotton fields of Tiptonville, Tennessee, a town abutting the Mississippi River in the northwest corner of the state. During the week little Carl had been soaking up the gospel songs the black field hands sang while they worked; on Saturday nights he was transfixed by the music coming out of the battery powered radio in the family kitchen, which was tuned to the Grand Ole Opry show emanating from Nashville and broadcast on station WSM. An elderly black man who worked the same fields as the Perkinses had taken Carl under his wing and taught him a few chords on his own guitar. Named John Westbrook, Carl always called him “Uncle John.”

It was “Uncle John” who taught Carl his first important lesson about musicianship. One late afternoon, when they gathered together after the picking was done, Carl struggled to play some basic chords and riffs Westbrook had taught him earlier. Seeing Carl’s frustration mount, Uncle John counseled a gentler approach. “See, Carl, it ain’t just in the guitar, it’s in the fingers,” Uncle John said. “And what I mean by that is it’s in the soul.”

“Uncle John, how can I get my soul in my fingers?” the befuddled pupil queried.

“Well, chile, lean your head down on that guitar. Get down close to it. You can feel it travel down the strangs, come through your head and down to your soul where you live. You can feel it. Let it vib-a-rate.”

These simple words—“Let it vib-a-rate”—had as much impact on Carl’s playing as any advice ever imparted to him. Whenever he’d get flustered and start fighting the instrument, he would hear Uncle John: “Let it vib-a-rate.”

Roy Acuff, ‘The Great Speckled Bird,’ 1968Hearing Roy Acuff’s music on radio prompted Carl to ask his father, Buck, for a guitar of his own. Desperately poor, the Perkins family could not afford the luxury of buying a musical instrument brand new. Instead, using a broom handle and an empty cigar box, Buck fashioned a crude guitar for his son. When a neighbor in tough straits offered to sell his used guitar for a couple of dollars, Buck scraped together the funds and gave his son a rare present. The body was dented and scratched, but any way you cut it, it was a Gene Autry signature model, and when Carl put his fingers on the worn-out strings (“burned up” is how he would characterize them in later years), his parents felt their son's whole being radiating pure pleasure.

Carl demonstrated a good ear for music and proved a quick study as a novice guitarist. The mystery of Acuff’s “Great Speckled Bird” fascinated him, and once he had real strings to work with, he taught himself the first few notes of the song. For a year he worshipped at the altar of Acuff, of “The Great Speckled Bird,” of Acuff’s roaring interpretation of A.P. Carter’s “The Wabash Cannonball.” Even as his repertoire grew, though, his technique remained rudimentary, his sense of rhythm predictably stiff. All that changed in 1939 when, again via the radio, he encountered another new Opry star, Kentucky-born Bill Monroe.

With his band the Bluegrass Boys, Monroe shook up country music. He and his brother Charlie had worked together as the Monroe Brothers before splitting into separately led bands. Their music—dubbed “bluegrass” by Bill in honor of his home state—was distinguished by spirited tempos, Bill’s adroit, breakneck mandolin solos, and his open wound of a voice, high, lonesome and searching. Monroe wrote many of his own tunes, but also drew on the bottomless well of songs handed down through the centuries from Irish and Scottish sources, especially dark, graphic tales of murder and betrayal. Beyond his advocacy of a new style, Monroe elevated the mandolin from supporting role to star attraction, much as Maybelle Carter had done with the guitar in the Carter Family.

Bill Monroe and the Bluegrass Boys, ‘Blue Moon of Kentucky’ (live, 1980)To James Rooney, author of Bossmen: Bill Monroe & Muddy Waters, Monroe said the music of Jimmie Rodgers, the Singing Brakeman who, along with the Carters, had inaugurated country music’s modern era after being discovered at the Bristol sessions in 1927, had been pivotal in helping him find his own approach. “Charlie and I had a country beat, I suppose,” said Monroe, “but the beat in my music—bluegrass music—started when I ran across ‘Muleskinner Blues’ [aka Jimmy Rodgers’s “Blue Yodel No. 8”] and started playing that. We don’t do it the way Jimmie Rodgers sung it. It’s speeded up, and we moved it up to fit the fiddle, and we have that straight time with it, driving time. It’s wonderful time, and the reason a lot of people like bluegrass is because of the timing of it.”

Monroe hit close to the feel Carl liked but could not yet execute. And the voice—that high lonesome sound—pierced Carl deeper than any other singer had ever done. Acuff’s emotionally stirring voice was a riveting, even haunting instrument, but the complexity of Monroe’s—a curious balance of determination and detachment, vulnerability and strength—told a story Carl may have been too young to fully comprehend, but he had no trouble feeling it burrowing in to his marrow, rattling around in his soul. The path it had sent him down made him feel more alive than he knew was possible, and he determined he would take it to a place where he could clear a way of his own.

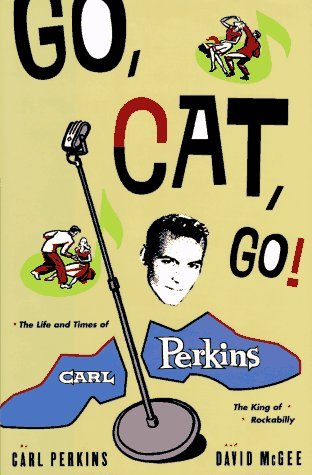

Part of this excerpt is taken from the authorized biography of Carl Perkins, Go, Cat, Go! The Life and Times of Carl Perkins, The King of Rockabilly, by David McGee (Hyperion, 1996)

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024