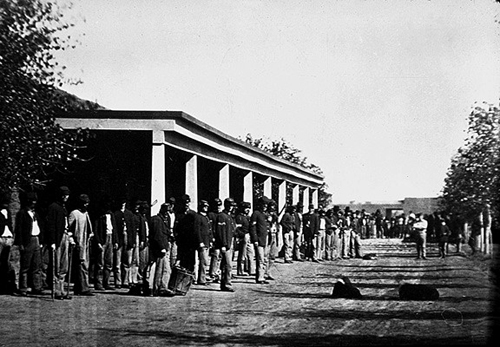

On October 31, 1862, Congress authorized the establishment of the military Fort Sumner at Bosque Redondo, to protect a new Indian Reservation situated on 40 square miles of land. The post was named for General Edwin Vose Sumner who died as the new fort was being built. Though some officers discouraged the selection of Bosque Redondo as a site because of its poor water and minimal provisions of firewood, it was established anyway. It was to be the first Indian reservation west of Indian Territory (Oklahoma,) with plans to turn the Apache and Navajo Indians into farmers with irrigation from the Pecos River. They were also to be "civilized” by going to school and practicing Christianity. To accomplish their plan, the U.S. Army made war on the Mescalero Apache and Navajo Indian tribes, destroying their fields, orchards, houses, and livestock. The Apache and Navajo, who had survived the army attacks, were then starved into submission. During a final standoff at Canyon de Chelly in Arizona, the Navajo surrendered to Kit Carson and his troops in January, 1864. Carson ordered the destruction of their property and organized the Long Walk to the Bosque Redondo reservation, already occupied by Mescalero Apaches. Before long, a small settlement grew up around the military post that was populated not only by soldiers but also by ranchers, stockmen and businesses supporting the fort. Billy the Kid would die here, shot by Sheriff Pat Garrett.A Belle Of Old Fort Sumner

By Walter Noble Burns

Ed. note: April 1881. Billy the Kid, shackled and chained, has executed an unbelievable, and exceedingly bloody, escape from the Lincoln, New Mexico, jail, where Sheriff Pat Garrett had brought him in advance of the Kid’s date with the hangman’s noose. A few days before the Kid’s May 13 execution date, Garrett had left Lincoln, heading for White Oaks, to pick up some lumber that would be fashioned into a gallows through which the Kid’s body would fall, convulse and come to a death rest in front of the Lincoln townsfolk. Waiting patiently for his “one in a million chance,” the Kid, while still manacled, had snatched a six-shooter out of the holster of Deputy Sheriff J.W. Bell during a game of monte, then shot and killed Bell who was trying to flee what he would have known was near-certain death if the Kid had a gun in his hand. Across the street, Deputy Sheriff Bob Ollinger, the other half of the Kid’s death watch squad in Garrett’s absence, was settling down to a meal when he heard what sounded like a shot coming from the jail. Ollinger hated the Kid with a passion; he took great pleasure in taunting Garrett’s prisoner, saying he would love to “plant eighteen buckshot between your shoulder blades” from his double-barrel shotgun, if only the Kid would make a break for freedom.

“It would be a joke if you happened to stop those eighteen buckshot yourself,” the Kid answered him on one of those occasions. “Eh, Bob?”

When he went off to eat, Ollinger slipped up and left his double-barrel leaning against a wall in the jail. The Kid knew it, and went for it as soon as he had overwhelmed and murdered Bell. Running towards the sound of what he thought was a gunshot, Ollinger circled around to the side of the prison where the Kid was housed.

“Hello, Bob!”

The Lincoln County jail, site of Billy the Kid’s bloodiest escapeOllinger knew the voice well. When he turned to face where it had came from, he was staring into the barrels of his own shotgun. The first blast of nine buckshot spun Ollinger around and he fell face first, dead, to the earth. The Kid, still shackled at the legs, hobbled out to the hated deputy’s body, and pumped the last half of the buckshot into Ollinger's lifeless form, then brought the butt of the gun crashing down on the corpse. “Take that to hell with you, you cowardly curd,” Billy snarled.

With the help of the jail cook, Old Man Goss, Billy freed himself of his chains, commandeered a black horse owned by county clerk Billy Burt and rode easy out of town. “At the edge of the village he passed a Mexican urchin,” Walter Noble Burns writes in his biography of Billy the Kid, The Saga of Billy the Kid, “and, at that time, according to the boy, he was whistling a merry little tune.”

But instead of riding hard into old Mexico, where he would have been beyond the reach of the U.S. law, Billy rode to Fort Sumner, to “the one woman of his dreams.” In the following chapter from The Saga of Billy the Kid, Burns reconstructs Billy the Kid’s life at Fort Sumner, based on interviews with people who were there when he met his fate.

***

Sunset on Old Fort Sumner Road, New MexicoBilly the Kid was a youth of many light affairs, but he loved but one woman. This at least is what the Southwest has believed for nearly fifty years. His love for her was his soul’s one clear drop of poetry. On his way to hell, it gave him his one vision of Heaven. Concerning the identity of his sweetheart, there has been much speculation. She lives in old Fort Sumner—that much is certain. When, later on in his story, Billy the Kid escaped from Lincoln, it is generally conceded he could have got quickly into old Mexico where he would have been safe from pursuit. Life and liberty beckoned him across the Rio Grande. But the love in his boy’s heart longed for his sweetheart and he headed straight for Fort Sumner. For the one woman of his dreams he risked his life in his life’s most desperate chance. For love of her he died.

Mrs. Paulita Jaramillo of New Fort Sumner, who in her youth was Paulita Maxwell, daughter of one of New Mexico’s famous families, throws much interesting light on this old sweetheart romance. She and Billy the Kid were friends, and the friendship of this good, pure girl was a gracious influence in his life. Time has dealt gently with Mrs. Jaramillo. No one would be so ungallant as to inquire how old she is, but it may be whispered that in 1881, when Billy the Kid met death in her home, she was a blooming girl of eighteen. Streaks of gray have only begun to show in her coal-black hair; when she smiles, the suspicion of a dimple still shows in the olive smoothness of her cheeks, and there is a sparkle in her black eyes that age has had no power to dim. It is easy to fancy her as the dashing beauty she is said to have been when she was the belle of old Fort Sumner.

Lucien Bonaparte Maxwell, dubbed ‘Emperor of New Mexico.’ New Mexico still bears remnants of the Maxwell name as Maxwell landmarks are scattered throughout the vast area he once controlled. It is said that no other person has ever surpassed his record for individual land holdings in the U.S. His epitaph: ‘Against Lucien B. Maxwell, no man can say aught, and he died after an active and eventful life, probably without an enemy in the world. Of few words, unassuming and unpretentious, his deeds were the best exponent of the man. He was hospitable, generous and upright, and dispensed large wealth acquired by industry and genius with an open hand to the stranger and the needy.’Mrs. Jaramillo united the blood of Spanish hidalgos and American pioneers. Lucien B. Maxwell, her father, was a friend and companion of Kit Carson, and at one time was reckoned the richest man in the Southwest. He was a native of Illinois and settled in New Mexico when the country was still a part of old Mexico. He married Señorita Luz Beaubien of noble ancestry, tracing back to the aristocracies of France and Spain. She was the daughter of Charles Hipolyte Trotier, Sieur de Beaubien, a Canadian, who embarked in the commerce of the Santa Fé trail and settled in New Mexico in 1823. Her mother had been Señorita Paula Labata, descended from a family that came to the New World soon after the conquest of Mexico by Hernando Cortez and arrived in New Mexico in the wake of Oñate’s pioneers. So Mrs. Jaramillo has, as her intimate background, the proudest family traditions in all that part of the country.

With Don Guadalupe Miranda, the Sieur de Beaubien obtained, as a reward for pioneer services, from the government of old Mexico a grant of land of vast extent in the northern part of the province of New Mexico, famous in later years as the Maxwell Grant. Miranda sold out his interest to Beaubien and, upon the latter’s death in 1864, Maxwell purchased all the land from Beaubien’s heirs and became sole owner of a tract larger than three states the size of Rhode Island and embracing more than a million acres. The land comprised in the original Maxwell Grant is to-day dotted with towns, timber claims, mines, farms, and ranches, and at an extremely modest estimate is worth fifty million dollars.

Maxwell built a palatial home at Cimarron, where for years he lived in a style of baronial magnificence. Here he dispensed lavish hospitality, and the guests who came and went in endless procession included traders of the Santa Fé trail which passed his door, cattle kinds, governors, merchants, army officers, an men distinguished in public life and international affairs in Europe and America. His cellars were stocked with liquors, champagnes, and costly vintages, and his table was laid each day for two dozen guests who ate their food from dishes of solid silver and drank their wines with chalices of solid gold.

Owner of great herds of sheep and cattle, this feudal lord of the old frontier finally sold his vast estate to Jerome B. Chaffee, David H. Moffatt, and Wilson Waddington for the reputed sum of $750,000 and lived to see the purchasers sell out to an English syndicate for $1,350,000, almost twice what they had paid him. Maxwell founded the First National Bank of Santa Fé, which he sold in 1871 to Stephen B. Elkins, Thomas Catron, and others. He lost a quarter of a million dollars which he invested in a corporation for the construction of the Texas Pacific Railway. Other investments proved unfortunate. Generous, improvident, picturesque, this magnificent old pioneer retired to Fort Sumner, where he died comparatively poor in 1875.

Mrs. Paulita Jaramillo of New Fort Sumner, who in her youth was Paulita Maxwell, daughter of one of New Mexico’s famous families, was good friends with Billy the Kid. According to Walter Noble Burns, ‘the friendship of this good, pure girl was a gracious influence in [Billy’s] life.’ She is shown here in an undated photograph with her husband JoséMrs. Jaramillo passed her childhood in frontier luxury on her father’s estate in Cimarron. Her mother died in 1881. The other Maxwell children were Pedro, Odila, Amilia, Virgnia, and Sophia. Pedro, known throughout New Mexico as Pete Maxwell, lived, until his death, at Fort Sumner, and in his later years was the richest sheep man in the Pecos Valley. Amilia and Odila became the successive wives of Don Manuel Abreu. Virginia married Captain Alexander Chase of the U.S. Army, and with her husband is buried at the Presidio at San Francisco. Sophia married Telesfor Jaramillo, a brother of José Jaramillo, to whom Paulita Maxwell was married in January, 1882. Of these children, only Mrs. Paulita Jaramillo and Mrs. Odila Abreu are left alive (1924).

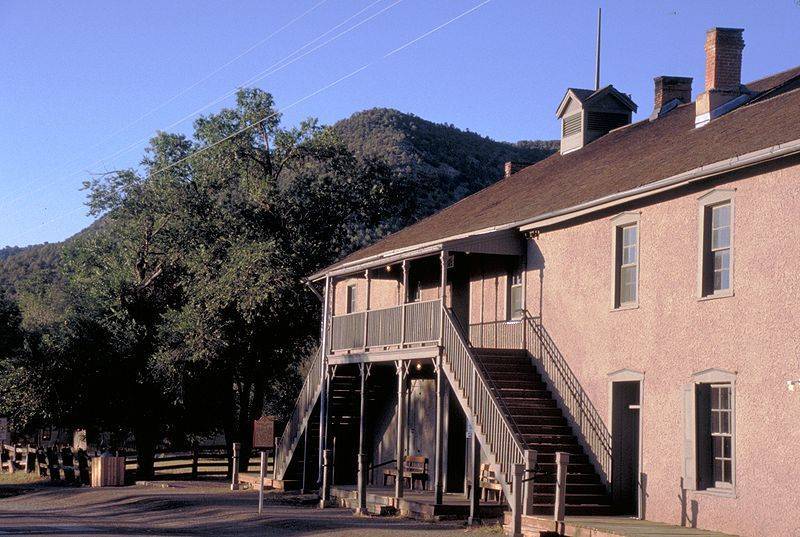

Where the ancient cottonwood avenue that was the glory of old Fort Sumner ends four miles to the north, stands new Fort Sumner to-day on the Belen Cut-off of the Santa Fé Railway. Don’t confuse old Fort Sumner with new Fort Sumner. They are fifty years distant from each other, though by linear measurement only four miles. One is the past, the other the present; one poetry, the other prose. New Fort Sumner is without tradition, romance, or picturesqueness. It seems asleep, but its slumber is not idyllic like that of Lincoln nor haunted by ghosts like that of White Oaks. It has the dreariness of stagnation. The raw town sprawls over its sandhills by the Pecos in sun-drenched ugliness. Here the road of dreams that leads out of the past and is shaded by trees rooted in romance, crashes head-on against the iron highway of a modern transportation system.

You find Mrs. Paulita Jaramillo in her own little cottage in the outskirts of the town. If the day is pleasant, she will perhaps be sitting in a rocking chair on her porch, working an embroidery or crocheting a mantilla.

“An old story that identifies me as Billy the Kid’s sweetheart,” says Mrs. Jaramillo with an indulgent smile, “has been going the rounds for many years. Perhaps it honours me; perhaps not; it depends on how you feel about it. But I was not Billy the Kid’s sweetheart. I liked him very, very much—oh, yes—but I did not love him. He was a nice boy, at least to me, courteous, gallant, always respectful. I used to meet him at dances; he was, of course, often at our home. But he and I had no thought of marriage.

Pete Maxwell“There was a story that Billy and I had laid our plans to elope to old Mexico and had fixed the date for the night just after that on which he was killed. There was another tale that we proposed to elope riding double on one horse. Neither story was true and the one about eloping on one horse was a joke. Pete Maxwell, my brother, had more horses than he knew what to do with, and if Billy and I had wanted to set off for the Rio Grande by the light of the moon, you may depend upon it we would at least have had separate mounts. I did not need to put my arms around any man’s waist to keep from falling off a horse. Not I. I was, if you please, brought up in the saddle and plumed myself on my horsemanship.

“Billy the Kid, after his escape at Lincoln, came to Fort Sumner, it is true, to see a woman he was in love with. But it was not I. Pat Garrett ought to have known who she was because he was connected with her, and not very distantly, by marriage. The night the Kid was killed, Garrett asked Pete Maxwell why the Kid was in Fort Sumner. Pete shook his head and said he didn’t know. But he merely wanted to save Garrett embarrassment. He knew and I knew. I was standing beside Pete’s chair at the time and I would have answered Garrett’s question if Pete, by a look, had not warned me to keep my mouth shut.

“But if I had loved the Kid and he had loved me, I will say that I would not have hesitated to marry him and follow him through danger, poverty, or hardship to the ends of the earth in spite of anything he had ever done or what the world might have been pleased to think of me. That is the way of Spanish girls when they are in love.”

With an air of frankness, Mrs. Jaramillo tells you the name of the woman who, she declares, was the sweetheart whose fascination drew Billy the Kid to his death. Mrs. Jaramillo’s answer to the conundrum that has intrigued the Southwest for almost half a century has, even at this late day, a certain piquant interest; but it is charitable, and perhaps wise, not to rake this ancient bit of gossip out of the ashes of the past. The woman Mrs. Jaramillo names has been dead many years.

“Billy the Kid, I may tell you, fascinated many women,” Mrs. Jaramillo continues. “His record as a heart-breaker was quite as formidable, you might say, as his record as a man-killer. Like a sailor, he had a sweetheart in every port of call. In every placeta in the Pecos some little señorita was proud to be known as his querida. Three girls at least in Fort Sumner were mad about him. One is now a respected matron of Las Vegas. Another, who died long ago, had a daughter who lived to be eight years old and whose striking resemblance to the famous outlaw filled her mother’s heart with pride. The third was his inamorata when he was killed.

“Fort Sumner was a gay little place. The weekly dance was an event, and pretty girls from Santa Rosa, Puerto de Luna, Anton Chico, and from towns and ranches fifty miles away, drove in to attend it. Billy the Kid cut quite a gallant figure in these affairs. He was not handsome but he had a certain sort of boyish good looks. He was always smiling and good-natured and very polite and danced remarkably well, and the little Mexican beauties made eyes at him from behind their fans and used all their coquetries to capture him and were very vain of his attentions.

Charlie Bowdre, running buddy to Billy the Kid, was killed by Sheriff Pat Garrett and his posse on December 23, 1880. Billy the Kid was buried next to him. At Old Fort Sumner, Charlie's wife, Manuela Bowdre, was, according to Paulita Maxwell, ‘a dark, glowing, slender little creature of high spirits. Poor girl, it broke her heart when Charlie Bowdre was killed by Pat Garrett and his man-hunters.’“We had quite a bevy of pretty girls in Fort Sumner. Abrana Garcia, Nasaria Yerbe, and Celsa Gutierrez had a Spanish type of beauty that you associate with castanets and latticed balconies and ancient courtyards filled with the perfume of oleander. They were very graceful dancers, too, and with these three, I think, Billy the Kid danced oftenest. Manuela Bowdre, Charlie Bowdre’s wife, was a dark, glowing, slender little creature of high spirits. Poor girl, it broke her heart when Charlie Bowdre was killed by Pat Garrett and his man-hunters. But time mends broken hearts and Manuela married Lafe Holcomb, a cow-puncher, and was living over in the Capitan when I last heard of her. Juanita Martinez, Garrett’s first wife, and Apolinaria Gutierrez, his second, were sparkling young women, who had the charm of gaiety and light-heartedness and were always surrounded by admirers at our dances. Juanita was the sister of Don Juan José Martinez, who still lives in new Fort Sumner. Everyone loved her and mourned for her when an unkind fate changed her bridal gown into a shroud three weeks after her wedding. Garrett was more fortunate in his second love affair. Soon after his marriage to Apolinaria Gutierrez, he moved to Roswell and I saw little more of him or his wife, but I always understood they were very happy together.

“You doubtless suspect our Fort Sumner dances were not very fashionable affairs. Well, perhaps not; but they were great fun. The girls were not burdened with wealth and did not get themselves up in expensive and elaborate toilets. But in their simple gowns, made by themselves for the most part, with perhaps a red rose in their black hair or a bunch of blossoms at their waist, they were alluring enough to set any man’s heart going pit-a-pat. Nor were they unskilled in the subtle graces and diplomacy of the coquette. They knew how to use their black eyes to good advantage, and they were adept in the old-fashioned Spanish art—gone now from the Southwest—of making their fans talk when their tongues were silent. I will venture it would be hard to find at modern balls and cotillions more spirited or graceful dancers than our Fort Sumner girls. No orchestra concealed behind palm fronds played for us, but we had very good music; generally six pieces—violins, guitars, clarinets, and sometimes a tambe or Indian drum

“It might surprise you to know that our dances were extremely decorous. Everybody attended them, old and young. We girls of Fort Sumner were not accustomed to dueñas, but with our mothers and grandmothers looking on at our merriment, we were quite well chaperoned. There was no drunkenness, no rowdyism. Our men would not have tolerated anything of the kind for an instant. The men did no wear evening clothes, but they lived up to the old West’s traditions of chivalry. I suppose you are amazed that an outlaw and desperado like Billy the Kid should have been a favoured cavalier at our dances. But in the code of those days, any man who was courteous to a woman was considered a gentleman, and no questions asked; and, as there was little law in the country, an outlaw who measured up to this simple standard was as welcome at Fort Sumner’s social affairs as anybody else.”

Paulita Meets Billy

You are naturally curious to know how this beautiful and cultured daughter of the House of Maxwell chanced to meet the Southwest’s most desperate man-slayer.

Telesfor Jaramillo, brother of José Jaramillo, was saved from certain death by Billy the Kid when the Kid intervened after a drunken Jaramillo had insulted the volatile José Chavez y Chavez, who had taken aim at Telesfor when the Kid showed up. ‘He said something in Spanish to Chavez, who at once put his six-shooter back in its holster, and the Kid took him by the arm and they walked away,’ Paulita Jaramillo remembers. ‘Mother and I always thought that Telesfor never would have lived to be my brother-in-law if it had not been for Billy the Kid that day.’“I have a perfectly clear picture of Billy the Kid the first time I ever saw him, “ says Mrs. Jaramillo. “He was eighteen years old and I was fifteen and back home for vacation from St. Mary’s convent school in Trinidad. It was the Kid’s first visit to Fort Sumner. He had ridden over form Lincoln with several of his men, among whom was José Chavez y Chavez. This Chavez y Chavez was a bad fellow; he later served a long term in the penitentiary; he was only recently released and now lives near Las Vegas. Telesfor Jaramillo, who was afterward my brother-in-law, was drunk and met Chavez on the street back of our house. Chavez wanted to shake hands with Telesfor and said, ‘You and I are cousins.’ That may have been true; I don’t know; but Telesfor, being drunk, repudiated the relationship. He drew himself up and refused to shake hands. ‘No thief is a cousin of mine,’ he said. That made Chavez very made and he drew his gun. ‘I’ll kill you for that,’ he said.

“My mother saw it all and ran out and caught Telesfor by the arm and tried to drag him away. ‘Don’t shoot him,’ she said to Chavez, ‘he’s drunk. Wait till he’s sober and settle it.’ But Chavez refused to be quieted. ‘I don’t care whether he’s drunk or sober,’ he said. ‘He can’t insult me.’

“Just then we saw a young man walking rapidly across the road toward us and someone in the little crowd that had gathered said, ‘Here comes Billy the Kid.’ I became very much frightened when I heard that name. I had heard many stories of Billy the Kid and his desperate exploits in Lincoln County war and I said to myself, ‘Now we will all be murdered.’

“The Kid had a hard little smile on his face when he came up to us and I was surprised that he looked so boyish and not a bit dangerous.

“‘Don’t let this man kill my friend,’ my mother begged of him.

“The Kid touched his sombrero to my mother. ‘Don’t be afraid, señora,’ he said. ‘I’ll straighten this out.’

“He said something in Spanish to Chavez, who at once put his six-shooter back in its holster, and the Kid took him by the arm and they walked away.

“Telesfor in the meantime was weaving about unsteadily, and we took him into the house. He had had a very narrow escape, which he didn’t seem to realize, being very drunk. But mother and I always thought that he never would have lived to be my brother-in-law if it had not been for Billy the Kid that day.”

Don Manuel Abreu, who lives on a ranch within view of the site of old Fort Sumner, tells a piquant little tale about Mrs. Jaramillo.

“Not long after Billy the Kid’s death,” says Don Manuel, “Pete Maxwell, Paulita, and myself were sitting one night in the living room at the Maxwell home in old Fort Sumner. It was growing late. The town and house were silent. Suddenly we heard a strange noise like softly padding footsteps. It gave us all a thrill. The Kid had been killed in an adjoining bedroom. The sound was ghostly. It ceased. It began again. Just like someone walking softly in stockinged feet.

“‘What is that?’ Paulita’s voice was touched with suppressed excitement.

“‘Can it be,’ I asked, ‘that the Kid has come back from the dead?’

“‘Every night since his death,’ observed Pete, ‘I’ve heard queer noises about the old house.’

“‘Pooh!’ Paulita shrugged her shoulders.

“‘But, Paulita,’ I urged, ‘they say the spirits of murdered men often return to haunt the place where they were killed.’

“‘Absurd,’ she replied. ‘I have no patience with people who believe in ghosts.’

“‘Have you heard nothing at night of late?’ asked Pete.

“‘Nothing.’

“‘Listen!’ The sound like padding footsteps started up again.

“‘Billy the Kid’s ghost,’ breathed Pete, and made the sign of the cross.

“‘I’m not afraid,’ said Paulita. ‘I’ll go see what that is.’

“‘Better not go,’ I advised her.

“She threw open the door and boldly stepped out on the porch. In a moment she came back laughing.

“‘The ghost of Billy the Kid, eh?’ She flung at us contemptuously. ‘It was nothing but a stray jackrabbit hopping along the porch.’

“Paulita’s discovery relieved the situation that had become oppressively spooky.

“‘So, Paulita,’ said Pete at length, ‘you’re not afraid of ghosts?’

“‘No, not a bit.’

“‘And you don’t believe the Kid’s spirit can come back?’

“‘Of course not.’

“‘Yet you would be afraid to pass his grave at night.’

“‘I’d not be afraid.’

“‘Oh, yes, you would

“‘I tell you I should not.’

“Pete puffed at his pipe a moment in silence.

“‘You talk very brave, little sister,’ he said. ‘I dare you to go out to his grave now. It is only a little way. What do you say? Will you go?’

“‘Don’t be silly, Pedro. Why should I do anything so crazy?’

“‘But you say you are so brave. Give us some proof of your courage.’

“Paulita shook her head.

“‘It would be foolish of me.’

“Pete looked at me with a smile.

“‘She’s afraid, Manuel,’ he said. ‘She hasn’t the nerve to go.’

“‘Well,’ I answered, ‘I don’t blame her. I wouldn’t go myself.’

“‘There is no reason for such an imbecile performance,’ answered Paulita.

“‘I’ll tell you what I do.’ Pete pulled out his watch and looked at it. ‘It now lacks a few minutes of midnight. I’ll give you ten dollars if you go out to Billy the Kid’s grave right now.’

“You’re only fooling,’ replied Paulita. ‘You wouldn’t pay me the money.’

“‘Here,’ said Pete, ‘I’ll put it up in Manuel’s hands.’

“He drew a roll of money form his pocket and passed me a ten-dollar bill. I waved it airily.

“‘The money is yours if you win it, Paulita,’ I declared.

“‘I’ll go,’ she said.

“‘But,’ inquired Pete, ‘how will I know you have been at the grave?’

“‘Why, you’ll have to take my word for it, I suppose.’

“‘Bring me back something to prove it.’

“‘What?’

“‘Oh, a weed, a wildflower, a pebble—anything. I will want proof.’

“Paulita marched out the door, through the gate, and on across the old parade ground. Pete and I stood on the porch and watched her fade out of sight in the moonlight.

Billy the Kid’s grave: all three men buried here were killed by Sheriff Pat Garrett and his posse“‘She’ll come running back scared to death in a minute,” remarked Pete.

“‘I’m not so sure,’ I replied.

“We waited a long time.

“ ‘She’ll never go through with it,’ argued Pete. ‘She’s a brave girl but she hasn’t the nerve to go all alone to Billy the Kid’s grave at midnight.’

“‘That’s the hour when ghosts are said to walk.’

“‘She’ll pick up a pebble somewhere to fool me and offer it as her proof and claim my ten dollars. You’ll see.’”

“Pete chuckled.

“She was gone so long we began to grow uneasy. Then at least we heard footsteps. Directly we made out her dim figure in the moonlight coming back.

“‘She seems to be carrying something,’ said Pete.

“‘Yes. What can it be?’

“‘The Lord knows.’

“Laughing merrily, Paulita stepped on the porch and shoved some strange looking object into Pete’s arms.

“‘Here’s your proof,’ she said. ‘Now give me my ten dollars.’

“Pete carried the object into the lighted parlour to see what proof she had brought. And what do you suppose it was?”

Don Manuel Abreu shook with laughter.

“It was,” says he, “the little wooden cross that had stood at the head of Billy the Kid’s grave. No possible mistake about it, either. There was his name painted on it.”

When Don Manuel’s sprightly anecdote is repeated to her, Mrs. Jaramillo smiles with a slightly embarrassed air.

“Yes,” she says, “I did that. But,” she adds hastily, “I sent a servant out to the cemetery next morning and had the cross put back in place.”

‘Every time the Kid rode in, Barney rode out…’

Mrs. Jaramillo, you discover, has a quaint gift for poking fun, and that immemorial quality of mankind known in this modern day as “four-flush” is a favourite butt of her ridicule.

“Barney Mason, Pat Garrett’s brother-in-law, lived in Fort Sumner for many years,” she says, “and wanted people to think he was much braver than he was. But despite his boastfulness and his pose as a bad man, Fort Sumner always took his courage with a few grains of salt. When Billy the Kid and his followers were at the height of their success, Barney pretended to be a great friend of theirs; he gave them information, warned them of danger, and could not do enough for them. But when Pat Garrett was made sheriff and the forces of law began to close in on the Kid, Barney had a change of heart. He accepted a deputyship under his brother-in-law and became as great an enemy of the Kid as her formerly had been a friend. This embittered the Kid, and he sent word to Barney that he was going to kill him on sight. Secretly the Kid’s threat scared Barney half to death, but he put up a brave show. ‘The Kid can’t scare me,’ he boasted. ‘I’ll teach him a thing or two if we ever meet.’

“But every time the Kid rode in, Barney rode out. He never got within a mile of the Kid if he could help it. One day when Barney was driving to town from Santa Rosa with his wife beside him on the wagon seat, he saw the Kid coming toward him on horseback along the road. The situation looked ticklish for Barney; the country was open range and not a tree or rock to hide behind, and a desperado who had sworn to kill him about to pass him within a few feet and face to face. In this crisis Barney did some quick thinking. While the Kid was still far off, Barney jerked her black mantilla off his wife and draped it about his own shoulders and clapped her sunbonnet on his own head. Then he snuggled down into his seat, made himself look as small as possible, and chucked up his horses into a brisk trot. With his face concealed beneath the sunbonnet, he drove past the Kid and was greatly relieved when he arrived in Fort Sumner to find himself still alive. Then he went strutting about town, telling how he had met the Kid on the road and had opened fire on him and the Kid had taken to his heels and had been lucky to escape behind a hill. ‘I told you what I’d do to that fellow if we ever met,’ boasted Barney.

“And along toward evening, the Kid came jogging into Fort Sumner and, as usual, the panic-stricken Barney got on his horse and ran away and hid himself in the hills. Everybody, of course, wanted to hear from the Kid all about his narrow escape from death at Barney Mason’s hands. When the Kid heard the story Barney had been telling, he bent double with laughter.

“‘I recognized him the minute I saw him,’ he said. ‘His mantilla and sunbonnet didn’t fool me. I would have killed him if his wife hadn’t been with him. I didn’t want to drop him over dead in his wife’s arms. His wife was all that saved him. But with his mantilla and his nice pink sunbonnet, wouldn’t he have made a pretty corpse?’”

The Odyssey of Billy the Kid’s Photograph

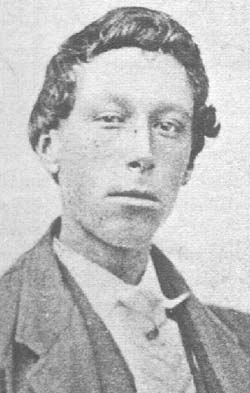

The only photograph Billy the Kid ever had taken was in possession of the Maxwell family for many years.

“It was taken by a traveling photographer who came through Fort Sumner in 1880,” says Mrs. Jaramillo. “Billy posed for it standing in the street near old Beaver Smith’s saloon. I never liked the picture. I don’t think it does Billy justice. It makes him look rough and uncouth. The expression on his face was really boyish and very pleasant. He may have worn such clothes as appear in the picture out on the range, but in Fort Sumner he was careful of his personal appearance and dressed neatly and in good taste.

“We had an old servant living with us who went by the name of Deluvina Maxwell. My father had bought her as a child for fifty dollars form a wandering band of Navajo Indians and she had been in our family ever since. Billy the Kid was Deluvina’s idol; she worshipped him; to her mind, there never was such a wonderful boy in all the world. When Billy was locked up in the Fort Sumner calaboose after his capture at Arroyo Tivan, Deluvina went to visit him. It was a cold winter’s day and, as the little jail was unheated, Deluvina came home and got a heavy scarf she had knitted and took it to her hero. In return for this kindness, the Kid gave her his only photograph, which he had carried around in his pocket. He would have given Deluvina nothing she would have prized more.

“My mother kept the picture in a cedar chest for years, and finally my sister, Odila, gave it to John Legg, a Forth Sumner saloon keeper and friend of the family. Legg was shot and killed and Charlie Foor, an executor of his estate, came into possession of the picture. When Foor’s house was burned down, the original was destroyed but fortunately many copies of it had been made. A wash drawing made from this photograph hangs in the Governor’s Palace at Santa Fé.

“Deluvina is still living at the ranch of my sister, Mrs. Abreu. She is very old and very fat and very superstitious. She, for one, will not pass, after dark, the little cemetery where the Kid lies buried. She declares stoutly that she has seen the ghost of a murdered Negro soldier there. But she says she has never seen the ghost of Billy the Kid. ‘Oh, no,’ she insists, ‘the spirit of that good child sleeps in peace.’”

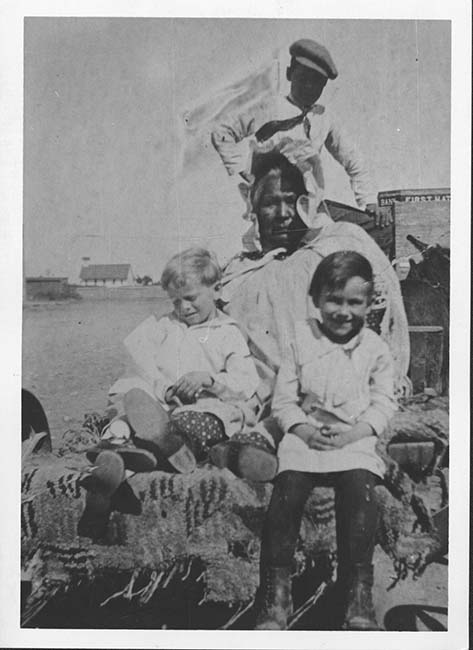

Deluvina Maxwell was a Navajo woman who worked as a servant to the Lucien Maxwell family. Lucien had bought her as a child for fifty dollars form a wandering band of Navajo Indians and she had been in our family ever since. ‘Billy the Kid was Deluvina’s idol,’ Paulita Maxell says. ‘She worshipped him; to her mind, there never was such a wonderful boy in all the world. When Billy was locked up in the Fort Sumner calaboose after his capture at Arroyo Tivan, Deluvina went to visit him.’ The children in the photo are unidentified except for the girl at right, Ida Harris, daughter of A.B. and Zenida Harris. This photo is dated circa 1924. (Photo courtesy the New Mexico State Records Center and Archives)For Pat Garrett, No Love Lost

Mrs. Jaramillo is not a great admirer of Pat Garrett and, as Garrett killed Billy the Kid, perhaps this is not to be wondered at.

“I remember the first day Pat Garrett ever set foot in Fort Sumner,” Mrs. Jaramillo goes on. “I was a small girl with dresses at my shoe-tops and when he came to our house and asked for a job as a cowboy, I stood behind my brother, Pete Maxwell, and stared at him in open-eyed wonder. He had the longest legs I had ever seen and he looked so comical and had such a droll way of talking that after he was gone, Pete and I had a good laugh about him. I came to know him very well; and after he had gone into business with old Beaver Smith, he used to spend many an evening in our home spinning yarns about his adventures hunting buffalo in the Panhandle. He was an easy-going, agreeable man, a good story-teller, and full of dry humour. He was fond of a social glass, and was a great hand to play poker and monte, and everybody liked him.

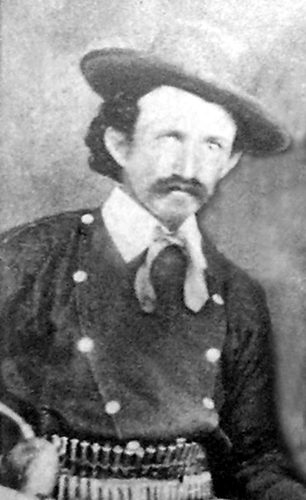

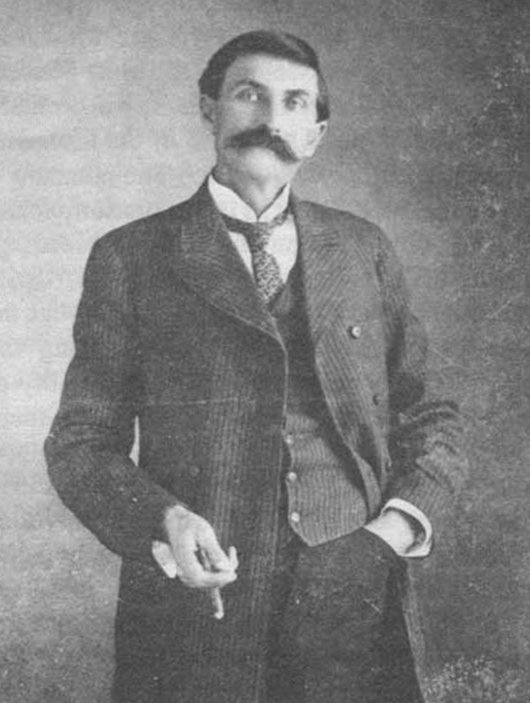

Sheriff Pat Garrett in an undated photograph. ‘I knew both men well and, in my opinion, Garrett was just as cold and hard a character as the Kid,’ says Paulita Maxwell. ‘The great difference between them was that Garrett had the law on his side and the Kid was outside the law. I will add this—and there are many men in New Mexico who will tell you the same thing—Pat Garrett was afraid of the Kid and of his own free will would no more have dared to enter a den of lions.’“Pat Garrett was as close a friend as Billy the Kid had in Fort Sumner and was on friendly terms with every member of the Kid’s gang. When we saw Pat and Billy together, we used to call them ‘the long and the short of it.’ Pat towered over Billy and would have made two of him. He ate and drank and played cards with the Kid, went to dances with him and gallivanted around with the same Mexican girls. I have seen them both on their knees around a horse blanket stretched on the ground in the main street gambling their heads off against a monte game. If Pat went broke, he borrowed from Billy, and if Billy went broke, he borroed from Pat. Sometimes they had friendly shooting contests. Both were wonderful shots. It was a toss-up between them when it came to the rifle, but Billy was the better shot with a revolver. I remember once Garrett emptied his pistol at a jackrabbit scampering through the street and missed it every time and Billy knocked it over with one bullet from his six-shooter. Oh, yes, Garrett and the Kid were as thick as two peas in a pod.

“Nothing ever gave Fort Sumner such a shock of surprise as Garrett’s selection by the cattle interests to be sheriff of Lincoln County. He was unknown, he had no experience as a man-hunter, and no reputation as a fighter. As far as anybody knew at that time, his only qualification for the office was his intimate friendship with the Kid and his men. He was familiar with all their old trails, their favorite haunts, their secret places of rendezvous and refuge. The one thing Garrett was called on to do as sheriff was to hunt down these old friends and kill them or put them in the penitentiary, and he did it methodically and in cold blood. I do not say this with malice; it is simply a fact. There is no law against a man’s turning against his old friends or hunting them to their deaths. But it was against the unwritten code of the frontier; and many men would rather have been killed themselves than undertake such a job. I will say for Garrett that he was absolutely frank about what he proposed to do. When he became sheriff, Billy the Kid knew exactly what it meant. From that time on, it was war to the death between them.

“I knew both men well and, in my opinion, Garrett was just as cold and hard a character as the Kid. The great difference between them was that Garrett had the law on his side and the Kid was outside the law. I will add this—and there are many men in New Mexico who will tell you the same thing—Pat Garrett was afraid of the Kid and of his own free will would no more have dared to enter a den of lions. Garrett finally killed the Kid, but the Kid was shot in the dark and did not have a chance on earth for his life. It was not cowardly in Garrett. He killed him in the only way the Kid could have been killed. But if the Kid had had an inkling of the danger he was in, Garrett probably would have been the one to die.”

Next Month: “The Rendezvous With Fate”—the night Billy the Kid died.

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024