Iraqi Maqam: Casualty Of Modernity And War

By Jacques Clement (AFP)

(left) an Iraqi Maqam ensemble from earlier times; (right) modern-day students at Iraqi Maqam Seminars in Labyrinth, CretePerforming before a half-empty room at Baghdad's Alwiyah Club, Taha Gharib is conscious that the music he has passionately played for decades—traditional Iraqi maqam—is dying.

Victim of the country's growing modernity and years-long violence, the poetic form of music that came to symbolise the newly-born Iraq that emerged after the fall of the Ottoman Empire is now played by fewer and fewer groups.

"Iraqi maqam risks disappearing with our generation," laments Gharib, who leads one of just five remaining maqam troupes in Iraq.

"People don't respect maqam anymore because today they prefer singers who just make noise," the 46-year-old says after his performance in Alwiyah, a rare oasis of cultural freedom in Baghdad, which remains plagued by violence.

Members of the Iraqi "maqam" group Angham al-Rafidain perform in Baghdad. Maqam ensembles typically include musicians playing a joza, an eastern lute, a tabla, and a santur, a trapezoidal box with 24 strings, though there are frequently more instruments involved, as a singer recites often centuries-old lyrics.Maqam ensembles typically include musicians playing a joza, an eastern lute, a tabla, and a santur, a trapezoidal box with 24 strings, though there are frequently more instruments involved, as a singer recites often centuries-old lyrics.

Gharib's quartet, for example, also includes a musician playing an oud, another type of lute.

Dating as far back as the end of the Abbasid era, which ran from the 8th to the 13th centuries, maqam became ingrained in Iraq's cultural identity in the decades following the country's modern founding in 1921.

"In the 20th century, maqam was a pillar of cultural life in Baghdad," notes Iraqi ethnomusicologist Scheherazade Hassan. While those who performed were typically those who had studied maqam for years, she says, it retained a wide audience.

She adds that maqam "historically fulfilled the purposes of a cultural ideal to foster respect for ethnic and social diversity ... it is an expression of collective identity."

‘Maqam Rast,’ Munir and Omar Bashir: This clip shows Iraqi Oud master Munir Bashir (1930-1997) and his son Omar Bashir playing an oud duet in the Arabic scale of Rast. Munir Bashir had a doctorate in musicology from Budapest, and was in constant rebellion against the misinterpretation of this music and its use for commercial ends. He has been credited with restoring credentials to a music that has become debased through bending to the taste for colonial nostalgia.But two factors were predominant in its decline: firstly, the rise of an Iraqi middle class who began to call for a wider variety of music, including Arabic pop.

And secondly, high levels of violence in the aftermath of the 2003 U.S.-led invasion that ousted dictator Saddam Hussein forced hundreds of thousands of Iraqis to leave the country, and maqam artists were no exception.

Another consequence of the violence was that many of the places where maqam was played closed their doors, and communal bloodshed made it difficult for performers of various sects to play in certain parts of Iraq.

As if to drive home the point of maqam's decline, as Gharib and his quartet play to a crowd of around 100 diners, Arabic pop music blares from adjacent rooms where two weddings are underway.

Maqam today is treated almost like an artifact in a museum, a remnant of a bygone era.

Taha Gharib, maqam singer and joza player"The ministry of culture calls on us from time to time to perform at recitals outside of Iraq, at the request of foreign countries," Gharib says, noting that he has had to take a job as a civil servant in the industry ministry because maqam no longer brings in enough income.

The slow death of form of music is evident also at the very institution that is meant to safeguard it in Iraq, the House of Maqam.

Given the decrepit building that houses it in central Baghdad to the high average age of those who come to listen to maqam players ply their trade, the typically sorrowful rhythm of maqam seems a fitting backdrop to its decline.

On this particular day, a musician performs for around a dozen listeners, singing of lost love:

"The flames of love make me cry/Others toast to love, but all I have is pain/I don't want to suffer any more, but I am drowning/I cry like a lost dove/Lost by day and by night."

Hussain Al-A3dhami, ‘Maqam Jammaal and Pesteh’: In Bahrain, November 11, 2005. Hussain is not only a maqam master, but also a teacher of the Iraqi maqam in Baghdad. He has written and published several books and research papers on the Iraqi maqam! He has also toured the whole world singing the Iraqi maqam with his orchestra : Safwat Muhammad Ali Al-Mousilli (oud), Alaa' Abul-Aziz Al-Simaawi (qanoon), Dakhil Ahmad 3arraan (jawza), Saif Walid Al-3obeidi (Santour), Sami Abel- Ahad ( tabla, percussion), Abdel-Kareem Harboud (naqaara), Ali Ismail Jasim (kishba), Falaah Ismail Al-Mousilli (tambourine).A maqam performance usually is concluded by an attached light song, the pesteh. In the pesteh, the instrumentalists from the ensemble take up the singing.While maqam techniques long used to be passed along as musicians rubbed shoulders at ubiquitous Baghdad cafes, this is no longer the case.

Instead, Mowaffaq al-Beyati, the head of the House of Maqam, advocates the creation of a school that teaches it to Iraqi youth.

"Maqam is one of the most difficult things to learn, and to sing, and this is especially true for young people today because they do not get any opportunity to hear it," he says.

In Beyati's favour is UNESCO's addition in 2008 of maqam to its Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity list, meaning Iraq can apply for funds to establish just such a school.

UNESCO, when contacted by AFP, said that no such application had yet been made, however.

An Iraqi music teacher addresses a classroom of students at a music school in Baghdad in November 2010. The Iraqi ‘maqam,’ an ancient poetic type of music that became a popular symbol in Iraq after the fall of the Ottoman Empire, is fading slowly, battered by modernity and violence.

At present, the only place interested students can learn maqam is at Baghdad's Institute of Musical Studies on the banks of the Tigris.

"Maqam is part of our identity, our roots—we cannot forget that," notes Sattar Naji, the director of IMS, where one quarter of the curriculum focuses on maqam.

"The public will tire of you if all you play is commercial music, but they will remain faithful if you have mastered maqam," says Naji, who in addition to heading IMS, also plays oud in Gharib's ensemble.

Naji says he is hopeful of a future revival of maqam, when his country puts the constant violence behind it, and recalls the Iraqi proverb that notes, "A happy soul sings."

Posted originally at France 24.com, a 24/7 international news channel with a mission to cover international current events from a French perspective and to convey French values throughout the world. It broadcasts its programs over the airwaves and over the Internet in French, in English and in Arabic. Culture is at the forefront of France 24’s programming.Also posted on December 8, 2010 at Iraqi Maqam, an education, non-profit blog exclusively dedicated to document and explain the ancient musical art of the Iraqi Maqam, and to preserve the memory and works of Iraq’s most prominent maqam masters. The majority of the works published on the site have been obtained through collectors of old broadcast recordings or private concerts and are readily available on the Internet. Send questions and comments to Iraqimaqam@gmail.com.

http://iraqimaqam.blogspot.com/2010/12/iraqi-maqam-emerges-as-casualty-of.html

***

To Give Voice To The Voiceless

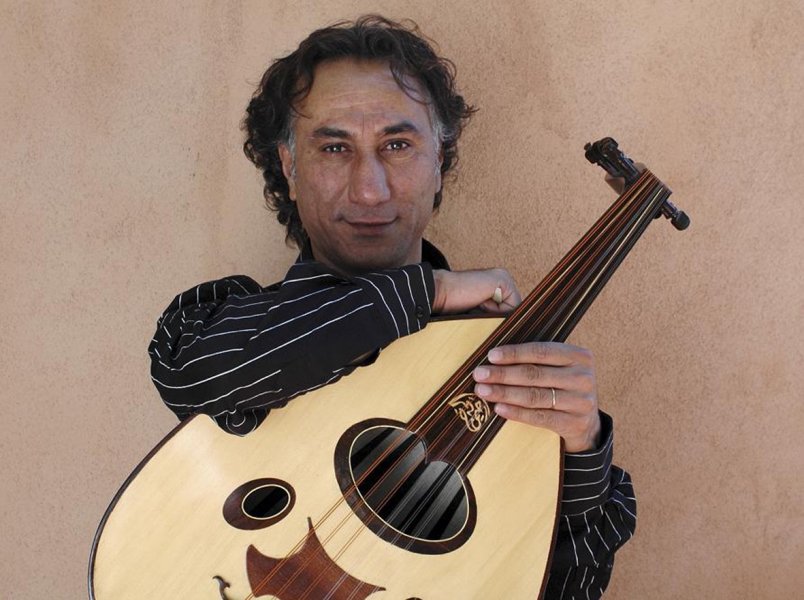

Iraqi-born, New Mexico-based Rahim AlHaj advances the traditional music of his country and sends a message of peace, compassion and love

In the United States at least no artist has done more than Iraqi-born New Mexico resident Rahim AlHaj to raise Americans’ consciousness about traditional Iraqi music and to spread, in his own music, a message the oud master defined in www.rootsworld.com as “peace and compassion and love. Those three concepts are in the music, and the drive is to learn, to understand, though not to know.”

Rahim AlHaj, Iraqi-born oud musician and composer now based in the United States, discusses his instrument and the importance of music to the Iraqi people:.Described in various press reports as “a true messenger of hope,” AlHaj, 42, a Baghdad native, was imprisoned twice by Saddam Hussein’s regime, owing variously to his refusal to write music honoring the country’s military endeavors in the 1980s, and to “Why?,” his song of resistance, capturing the hearts of his countrymen and the attention of the authorites, who took away his ouds and put him in prision. Two years later AlHaj fled Iraq, making his way from Syria to Lebanon and, finally, in 2000, to the U.S. and New Mexico. He arrived speaking little English and with no reputation to speak of as a musical artist. (How did he wind up in New Mexico? After being granted political asylum in the U.S., he requested Catholic Charities, his sponsoring organization, send him to the Land of Enchantment, “because New Mexico was thought of as a center of art and culture and because of the similarity of the climate, a desert, to Iraq.”)

He got busy, to say the least.

“I knew no English. I learned from reading Nietzsche because I heard from a friend that the best way to learn a language is to choose a book that you love in your own language. So I started speaking English in Albuquerque by quoting Nietzsche in English translation. Then I went to the local community college to try to learn more English. Catholic Charities found me a job, at McDonald’s. I did not at first understand and I thought they wanted me to play background music for diners in a restaurant. So, I tried to politely explain that my music is really not suitable for dining. When the caseworker told that I would be a dishwasher, I lost it. I threw every bad English word I knew at him.

“Instead of that, I worked as a security guard for six dollars an hour, but that was not going to pay back the money that I owed Catholic Charities for my passage here. So I rented a hall at the University of New Mexico myself, and a friend helped me put up hand-drawn flyers announcing an oud concert, my first in America.”

On the strength of advance notices of the concert in the Albuquerque newspaper, the concert sold out. Invitations to perform elsewhere around the state followed, and soon AlHaj was touring the length and breadth of the States.

Rahim AlHaj recording his 2006 CD, When The Soul Is Settled: The Music Of IraqHe has performed at the Kennedy Center (June 2006, to mark the release of his CD When The Soul Is Settled: Music of Iraq), in Europe and throughout the Arab nations of Africa and the Middle East. In 2004 he not only returned to Iraq to visit his family, and to play his music for them. As he told RootsWorld.com, his unlikely benefactor for the trip home was actress Ali McGraw, who introduced herself to AlHaj following his concert in Santa Fe. He knew her from Love Story (“It was the first movie I cried at”). They became friends and she made the arrangements for AlHaj’s trip back to Iraq. “My mother and Ali have exchanged gifts. She is a very good person. In Baghdad, I played for my family by kerosene lamps; there was no electricity. It had been thirteen years since I had seen them.”

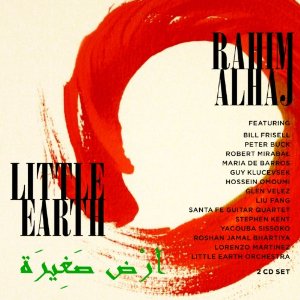

Now he is celebrating across the board raves for his latest album, Little Earth, on which AlHaj blends his original compositions rooted in the traditional styles of his homeland’s sama’i (“Sama’i Baghdad”) and sea chanteys (“Sasilors Three”) into multicultural journeys blending western and eastern disciplines into a true border crossing blend. Accompanying him on this journey are some musicians familiar to American listeners—Bill Frisell and R.E.M.’s Peter Buck, along with Cape Verde’s Maria de Barros and Mali’s Yacouba Sissoko.

“It was a dream to compose music for all the world,” AlHaj told a reporter for www.gotmusictalent.com. “The challenge of the project was to do more than just get together and jam. It was not just for fun.

“Though most sama’I are written for traditional Arabic instruments, I wrote it for a Western string quartet, but they have to play it in the Arabic way, including the special intonation and microtones—we have eight notes between B and B-flat. It was unique, the first time this form was performed by Western musicians on classical strings.

“I think of it as a conversation between East and West, a dialogue.”

A dialogue between East and West: Eyvind Kang (violin), Bill Frissell (guitar) and Rahim AlHaj (oud) perform ‘Baghdad/Seattle Suite,’ at Walker Arts Center, February 2010, with commentary by Frissell.As an artist persecuted by the Hussein regime, AlHaj is using the platform and security American affords him to pursue a larger mission with his music. Enlightenment came long before the Americans invaded Iraq, specifically during the brutal Iran-Iraq War of 1980-1989 in which Iran suffered an estimated one million casualties, killed or wounded (and ongoing casualties from Iraq’s use of chemical weapons) and Iraq reported an estimated 250,000 to 500,000 killed or wounded.

“When I started to understand the world, I started to understand justice,” AlHaj told www.gotmusictalent.com. “I felt like I was responsible and obligated to make all my music give voice to the voiceless.

“The music energizes people,” he told www.rootsworld.com. “It may influence them, and they may take action. The music contains the drive for the message of peace and compassion and love. The music should be involved with real life, we should talk about important matters. In Iraq right now, as in most of the world, what is vital is what we can find in that brings us together, not so much that tears us apart. I try to talk about these things, about the common links between us all, at my concerts, not just provide entertainment.”

***

Little Earth: Finding a Path To Peace

"The musicians use their own sound and environment-I don't want them to imitate me—but they need to play the composition right, with the influence from the Middle East and the maqam," Rahim AlHaj notes. "This music is composed music; we're not just jamming. It's all written."

Within these compositions on Rahim AlHaj’s Little Earth, however, collaborators found new means of expression, using a language that they shared with AlHaj. Robert Mirabal, the Taos Pueblo Indian renaissance man and flute player, turned an Iraqi lullaby into a statement in his language of Tewa ("Lullaby"). Guy Klucevsek managed miraculously to get his accordion to hit the right quarter tones ("The Searching"), while Chinese p'ip'a (lute) player Liu Fung found a way to make her pentatonic work with AlHaj's maqam modes ("River"), all to his great amazement.

The musical encounters often had a strong dose of kismet, as AlHaj's work with Cape Verdean singer Maria de Barros proves. When recording took AlHaj to California, he met with de Barros and they struck up a conversation. AlHaj mentioned a piece dedicated to the memory of his mother and the warmth that emanated from her, de Barros exclaimed that she had Portuguese lyrics about her mother. The result ("Missing You/Mae Querida") was more than a Cape Verdean morna being played by an oud; it was the bittersweet swing of de Barros's home intertwined with the soulfulness of Iraqi maqam.

This soulfulness—the moan of a woman in mourning, the sigh of a palm tree collapsing under gun fire-remains AlHaj's constant companion. It, and AlHaj's political commitment to peace—continue to inform his work, and led him to close collaboration with a musical legend from his country's erstwhile enemy, Housein Omoumi, master of the Iranian ney (traditional flute).

These elements are felt most powerfully in "Qassim," a piece memorializing his vivacious and optimistic cousin killed during the U.S. occupation. "I needed to tell my cousin's story in music. Iraqi women cry out in grief from their stomach, very low," AlHaj reflects. "The piece starts with the sound of the horror at what happened. An Iraqi woman's cry, thanks to Stephen Kent's didgeridoo, and the rhythm of the piece are driving, insisting to be heard."

Beyond the sorrow and insistence on telling the stories of those without voice, AlHaj has found a new contentment and sense of place in the U.S., and more mournful pieces are joined by sprightly expressions of pure joy. Works like "Morning in Hyattville," inspired by a cheeky mockingbird and augmented by guitarist Bill Frisell, and "Athens to Baghdad" where AlHaj explores what he playfully calls "a place of sweetness" with his friend and sometime collaborator Peter Buck of R.E.M.

It is this union of the bitter and sweet, the harsh and the soothing, which gives AlHaj's vision its punch. For AlHaj, his work is about far more than curious peregrinations and sonic juxtaposition. It's about finding a path to peace and ending the suffering of the women and children, the bold minds and kind spirits, he witnessed.

"Of course, musicians from opposite sides in conflict can come together and make music," AlHaj states. "But we must figure out how to make music together before we become enemies, or we will prove ourselves fools. If we can hold that ideal high, as a principle, we can make it into fact. We will make it real and the earth will indeed become little."

(excerpt from review by Jamos at www.gotmusictalent.com, Jan. 3, 2011.)

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024