Taking this double-disc journey with Stevie Ray and the redoubtable Double Trouble is to marvel anew at their collective achievement, and to be struck dumb by the enormity of Stevie Ray’s artistry.The Ascendant Moment

Late-Night Thoughts on Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble’s reissued Couldn’t Stand The Weather

By David McGee

COULDN’T STAND THE WEATHER: LEGACY EDITION

Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble

Epic/LegacyWhen Couldn’t Stand the Weather was released in 1984, Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble were far removed—commercially, that is—from most of their blues brethren, and in fact were far removed from most so-called rockers as well. Think back to 1983 when the band’s debut album, Texas Flood, appeared, and recall if you will how that long player cut through the bullshit of British fashion bands and techno-pop, synth-pop or whatever you want to call the garbage that was infiltrating the rock mainstream. The guitar gods were on sabbatical: Johnny Winter battling drug addiction, Jeff Beck in virtual seclusion, Jimmy Page in virtual silence, Eric Clapton becoming a pop star.

Then along comes SRV to administer an enema to the scene and prove once again the laudable instincts of John Hammond, who had taken the band’s demo to Gregg Geller, then head of A&R at Epic Records, which led to a recording contract. Geller, who had been actively building Epic’s new wave roster (he famously signed Elvis Costello, among others, and now jokes that at the time the Stevie Ray album came his way he was “Mr. New Wave” at Epic), was a roots guy through and through—a rockabilly and blues aficionado, he had, two years prior to Stevie Ray entering his life, produced and wrote authoritative liner notes for Rockabilly Stars, an essential three-volume, six-LP Epic reissue of rockabilly nuggets by artists who, apart from, say, Carl Perkins and Charlie Rich, were then known only to the hardcore rockabilly crowd (the Collins Kids, Billy Brown, Ronnie Self, et al.). Geller may joke about having been “Mr. New Wave,” but he was also the right person for Hammond to entrust with the Stevie Ray Vaughan recordings.

The music Hammond brought to Geller has been mischaracterized over the years as “demos.” In fact, the band had recorded its album at Jackson Browne’s Down Town Studios in Los Angeles—hardly a low-tech facility. What Geller heard when he cued up the tape Hammond had given him was “pretty much the album” the band had produced on its own, Geller told TheBluegrassSpecial.com. “It wasn’t mixed yet, wasn’t totally finished, but it was pretty close. Once we agreed to a deal they took it into Media Sound [a New York studio] and finished it up. There might have been a few overdubs, then some mixing, and that was it.”

Hammond wasn’t taking a shot in the dark by bringing Stevie Ray to Geller’s attention. The two men had a mentor-pupil relationship dating to their time working together in the fabled “Black Rock” headquarters of CBS Records on 6th Avenue and 53rd Street, before Hammond left the company to form his own label, which had a pressing and distribution deal with CBS. At the time the Stevie Ray tapes came his way, though, Hammond’s label was floundering; “he had some backers who were somewhat fly by night, and the money had ran out,” Geller says. “He had Stevie but he didn’t have a label. For years John would come by my office and play me stuff. Sometimes it was interesting; sometimes it was really interesting, but generally it wasn’t something I felt we could release successfully. And a lot of times it was stuff that he couldn’t bring himself to say ‘no’ to the artist; that kind of fell to me. I’d do anything for John, though. He was my mentor.”

At the opening salvo of SRV and Double Trouble, Geller says he “flipped.” First, it was something earthy and gritty surfacing in the increasingly synth-driven New Wave landscape, and it spoke the musical language Geller loved. Second, it addressed an audience the mainstream music of the day had abandoned.

“The first thing I heard was ‘Lovestruck Baby,’” Geller recalls. “It was like a bolt out of the blue. I have this theory, the ‘gap’ theory, which is that there are certain kinds of music for which there is always an audience. And occasionally the market doesn’t satisfy that audience. There’s a gap where that audience isn’t being supplied with what it wants to hear. To me that always explained the success of the first America album—everybody wanted another Neil Young album, so they got their fake Neil Young album. Stevie obviously was no fake, but who else was there? You know, Eric Clapton was making pop records. There was just nothing like it at the time. I figured all those folks out there that like great guitar, how could they resist?”

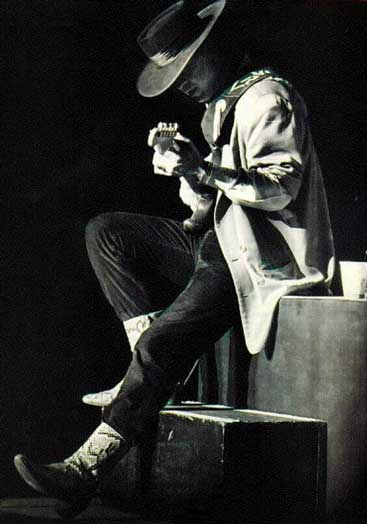

Stevie Ray Vaughan, ‘Lovestruck Baby,’ live in New Orleans, 1987, with Reese Wynans on keyboards. When Epic A&R director Gregg Geller heard the recorded version on the album the band had recorded at Jackson Browne’s studio, he described the feeling as being ‘like a bolt out of the blue.’ Geller signed SRV and Double Trouble, Epic released the album as Texas Flood, and worked it to the tune of half a million in sales.Well, they couldn’t resist. Texas Flood sold half a million copies—granted, no Thriller, which had come out the year before, but Michael Jackson not only had a great record on his hands, but a history, a following and was on an artistic trajectory almost two decades in the making. But between MJ and SRV you might have had some faith in the long-term health of the music mainstream, once Flock of Seagulls and all those other creeps did their inevitable fade into obscurity. In a way, Texas Flood was a greater achievement than Thriller, because so much was set up for Michael to support his extraordinary achievement in the studio on its way to near-unprecedented sales and cultural impact (not least of all, Michael had been setting himself up, building to his Thriller moment since the Jackson 5 emerged, nearly getting there with his extraordinary Off The Wall album), whereas SRV toiled in the backwaters of the blues, a genre the mainstream music press had pretty much written off then exactly as it has since Stevie Ray’s helicopter plowed into a hillside in the early morning hours of August 27, 1990, following his appearance the night before at the Alpine Valley Music Theater. But Texas Flood went gold, against all odds, it seemed, as did each of the band’s subsequent four albums. Thanks to Stevie Ray and Double Trouble, a lot of blues artists found more work at better pay, and the genre itself was revitalized. Indeed, talk to a lot of promising young blues artists emerging now—especially female blues artists—and they all will cite Stevie Ray as inspiring their love of the music as well as their passion for blues guitar.

Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble tear up Hendrix’s ‘Voodoo Child (Slight Return),’ live at the El Mocambo in Los Angeles, 1983Couldn’t Stand The Weather was the 1984 followup to Texas Flood. After a year of steady touring SRV and Double Trouble—bassist Tommy Shannon and drummer Chris Layton—were a well-oiled unit, having been together since 1981 and, since Texas Flood’s release, on the road for a year and half solid. Now they were playing with even greater power and confidence than they had displayed so impressively on Texas Flood. With John Hammond behind the board as executive producer and weighing in with pithy, on the mark observations about the performances that helped steer the whole exercise in the right direction, Stevie Ray and company cut loose, and you can sense exactly how loose in what became the album’s opening cut, a cascading flurry of speed-picked notes and pounding rhythm titled “Scuttle Buttin’,” a reworked attack on SRV hero Lonnie Mack’s “Chicken Feed” that became the standard Double Trouble set opener. More so than Texas Flood, Couldn’t Stand the Weather demonstrated how deep and wide were the influences Stevie Ray had absorbed: Mack being the inspiration for “Scuttle Buttin’,” Stax (i.e. Steve Cropper) inspiring the soulful title track, B.B. King being the looming presence in the mournful, thick-toned single-string ruminations of “Tin Pan Alley (Roughest Place in Town),” and two unabashed tributes to bluesmen he particularly admired in a gritty, crying treatment of Guitar Slim’s signature song “The Things (That I Used To Do), and most famously, the heavily wah-wahed, piledriving treatment of Jimi Hendrix’s “Voodoo Child (Slight Return),” a real test, given Hendrix’s God-like stature, that Stevie Ray passed with flying colors in divesting himself of a powerful, impassioned vocal and evoking the Hendrix instrumental attack while adding his own textures and complementary riffs to the song’s basic template—it was, at once, a moment when Stevie Ray embraced the past and pointed the way to the future, as Tommy Shannon has observed. There were other surprises: “Honey Bee,” a Stevie Ray original incorporating tough, lyrical Texas blues guitar in a classic, driving R&B framework; and the original album’s closing number, “Stang’s Swang,” a smooth, lounge-style small combo blues featuring sax and drums (Stan Harrison on sax, with drumming supplied by the Fabulous Thunderbirds’ Fran Christina) inspired by the cool organ-trio jazz outfits of Jimmy Smith and Brother Jack McDuff, with SRV working on some riff patterns, long, elegant single- and double-string lines and octave phrasings that summon the spirits of Wes Montgomery and Kenny Burrell, who played with Smith and McDuff and occupied a place high in Stevie Ray’s guitarist pantheon.

In Austin, Texas, an eight-foot statue of Stevie Ray Vaughan stands on the shore of Town Lake, near Riverside Drive & South First StreetThus the album proper. Remastered and reissued this past summer by Epic/Legacy, this new double-CD edition (produced, by the way, by the aforementioned Gregg Geller) is fleshed out in grand fashion. Disc One contains the original eight-track Couldn’t Stand the Weather album plus another 11 bonus tracks. Of the latter, four appeared on the 1991 The Sky Is Crying collection comprised of cuts recorded between 1984 and 1989 (including his near-seven-minute Grammy winning exploration of Hendrix’s “Little Wing,” a masterful, multi-textured demonstration of coiled emotions bursting forth in rampaging outbursts between sections of intense, wrenching introspection); four others appeared on the 1999 expanded reissue of this album (among those highlights: a terrific, ebullient strut through Freddie King’s “Hide Away,” Stevie’s tone alternately astringent and robust but always with a smiling countenance as Shannon and Layton keep the bottom nailed down but propulsive—this is the sound of Stevie Ray having a grand old time with a tune he knows inside out and can take liberties with before pulling it back to its familiar moorings); and three are previously unreleased:; a more propulsive, more aggressive reading of “Stang’s Swang,” with SRV for a different guitar with an airier tone and no sax to add the wee small hours element to the effort; and the real knockout punch, “Boot Hill,” a furious, incendiary, merciless blues that owes something to Arthur Crudup’s “Look Over Yonder’s Wall” and features Stevie Ray spitting the lyrics with impunity while deploying his guitar in howling, piercing fashion.

An aggrieved, howling take on the Elmore James classic, “The Sky Is Crying,” is very nearly as remarkable for Stevie Ray’s powerful, despairing vocal as it is for his piercing, complementary guitar voicings. The subtext of this reissue, in fact, is the strength of Stevie Ray’s vocals—his guitar was so formidable a weapon in his musical arsenal that the expressiveness, the soul, in his voice is often overlooked or underrated, but he could flat bring it when he locked into a lyric and invested it with the same humanity he brought to his playing.

“I always like to stress this,” Gregg Geller points out. “As great as the guitar was—undeniably great—what struck me was how well he sang. If you think about all the white blues guitar players, from Johnny Winter to all those guys out of England, to me the vocals always rang false. It always sounded like they were trying to sound black. Stevie just sounded like himself, totally natural. That’s what really did it for me. That’s why I felt so confident about Texas Flood. That to me placed him head and shoulders above the competition—(laughs) of which there really was none.”

Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble, ‘Scuttle Buttin’,’ the band’s standard set opener and the first track on Couldn’t Stand the WeatherDisc Two is as simple as it is complex: a live show recorded in Montreal on August 17, 1984, when Couldn’t Stand The Weather was fresh and its success had raised the stakes for the band, a challenge Vaughan, Layton and Shannon met at every level. This was a point where SRV and Double Trouble were stepping up to be not only the best blues band in the world but among the best bands in any genre. This is a disc meant to be played loud, simply because it sounds so good turned way up—the rhythm section’s power, the guitar’s transcendent lyricism, and the voice’s overflowing passion for the moment at hand. “Voodoo Child (Slight Return)” gets a near-12-minute interpretation—an archeological dig of epic proportions not even hinted at on the awesome studio version even in which Stevie Ray finds a way to bring the influences of about three decades’ worth of electric guitar stylists to bear on his solo odyssey; “Love Struck Baby” cooks with the ebullient, harmless horniness of a Chuck Berry groover; “Cold Shot” stomps rhythmically even as Stevie Ray’s vocal exudes tear-stained heartache over love gone awry (“remember the way that you loved me/do anything I said/now I reach to kiss your lips/it just don’t mean a thing/that’s a cold shot, darlin’/yeah, that’s a drag”); “Stang’s Swang” takes on its third incarnation here, considerably speeded up from the two studio versions heard on Disc One and serving here as a bit of an R&B frolic as a prelude to one of Stevie Ray’s most thoughtful, ruminative workouts on disc, the lovely 11-minute “Lenny,” named for his wife, “a little serenade for the woman,” he says, off Texas Flood. It’s been said SRV here channels Eric Clapton, B.B. King and Albert King all at once—Freddie King, too, for that matter—but in the end all the free flowing lyrical lines, the shimmering octave chords, the tender single string yearnings, all these are about the deep, indelible feelings Stevie Ray best expressed when he was being musical. Taking this double-disc journey with Stevie Ray and the redoubtable Double Trouble is to marvel anew at their collective achievement, and to be struck dumb by the enormity of Stevie Ray’s artistry.

Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble (with Reese Wynans on keyboard), ‘Cold Shot,’ from Couldn’t Stand the Weather, live on Austin City LimitsNot to be dismissed either is the supportive, avuncular presence of John Hammond. The legendary producer, who had signed Bessie Smith, Aretha Franklin, Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen, among others, would show up at the studio carrying the day’s New York Times, a cup of coffee and, in a brown paper bag, his lunch. As the band worked, he sat behind the console seemingly absorbed in the Times but actually listening intently to the goings-on and interceding when direction was needed. To Hammond’s biographer, Dunstan Prial, Layton recalled Hammond’s respect for the trio as a whole unit, not Stevie Ray and his backing band. “What really struck me about him that I always appreciated was that what we had was like a family,” Layton said. “Stevie was such an incredible talent that no matter what situation he played in, whatever group of musicians, he still always shined, he just shined. So I’m not the world’s greatest drummer. We’re probably not the world’s greatest band, but we all love each other, we care about each other, and John recognized that immediately.”

Shannon augmented Layton’s take, telling Prial: “[Hammond] has the insight to realize that we were a band. That’s how we played. It wasn’t like Stevie was over here and we were over here. It was part of his genius that he saw that. Just being around us for a few minutes he realized that. Nothing slipped past him.”

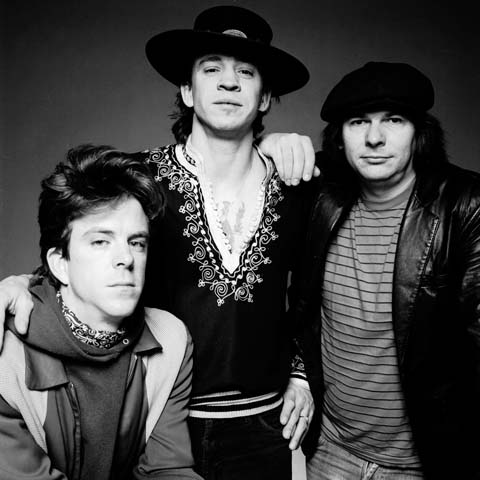

(from left) Chris Layton, Stevie Ray Vaughan and Tommy Shannon: ‘The three of us were so much on the same page, in terms of politics and social justice, how you treat your friends, neighbors and people in general, and one’s own personal ethics and morals, and of course that crossed over into the music,’ Layton recalls.Stevie Ray was only getting started on that fateful night in 1990 when he climbed aboard a helicopter in East Troy, Wisconsin. In these moments retrieved from 1984, though, is something beautiful and timeless, something beyond the sheer impact of these musicians’ synchronicity in moving towards goals each knew was within reach. In the years after this, drug addiction would almost undo all they had accomplished, but they retreated from the abyss and regrouped for another charge at greatness. Anyone who knew Stevie Ray Vaughan knew he would bring it all back home once he got straight, and that’s exactly what was happening in his personal and professional lives at the moment of his passing. Here then is the first ascendant moment captured, in all its dimensions. Chris Layton sums it up best in his comments to Guitar World’s Andy Aledort, who penned the insightful liner notes to this set:

“The three of us were so much on the same page, in terms of politics and social justice, how you treat your friends, neighbors and people in general, and one’s own personal ethics and morals, and of course that crossed over into the music. That made for a really great type of union—a deep connection and chemistry—that we shared. I think the audience got a reading of the type of relationship and connection the three of us had, and, without analyzing it, they could feel it, and it had a meaning to them. It’s something that simply cannot be put into words, but it’s undeniable.

“By the time we made Couldn’t Stand The Weather, we knew that we were there. And all of the great opportunities that arose as we grew in success simply strengthened our belief in ourselves. It was a confirmation in something I had believed in all along, and I could see that I wasn’t wrong. I knew we had a great thing, and I always had hoped that other people would feel that way, too. It was strength upon strength: all of the strengths that we had developed and assimilated were coming to bear on this record.”

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: [email protected]

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: [email protected]

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024