‘He Threw The Ball Faster Than Anyone Who Ever Lived’

Bob Feller

November 3, 1918-December 15, 2010

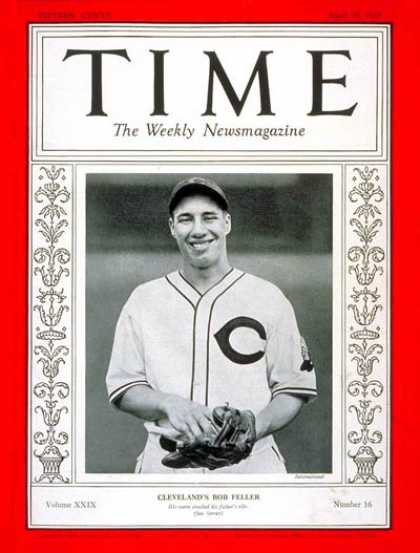

Bob Feller, “Rapid Robert” and “Bullet Bob” of baseball legend, who spent his entire 18-year Major League career with the Cleveland Indians, winning 266 games (despite leaving the game to serve in the Navy for four years during WWII) and striking out 2,581 hitters (leading the league in this statistic seven times), pitching three no-hitters and 12 one-hitters, died on December 15, 2010 of complications from leukemia. He was 92. He had pitched as recently as June 2009, as the starter in the inaugural Baseball Hall of Fame Classic, which replaced the Hall of Fame game at Cooperstown, NY. Baseball historians have speculated that his win total might have been as much as 350 and his career strikeouts some 3000-plus had he not joined the war effort. He enlisted on December 8, 1941, the day after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, and served as Gun Captain aboard the USS Alabama. He was decorated with five campaign ribbons and eight battle stars; his bunk on the Alabama is marked at Battleship Memorial Park in Mobile, AL.

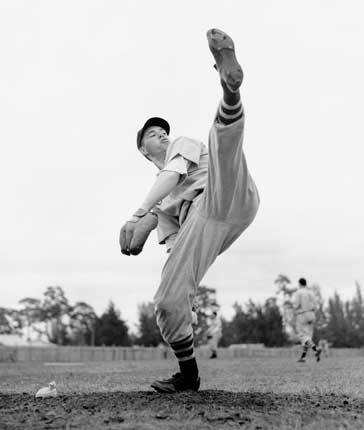

'Bob, that's what a I call a smart pitch'—17-year-old rookie Bob Feller gets a pitching lessonBorn and raised on a family farm in Van Meter, Iowa, Feller always said his arm strength came from the long hours he spent milking cows, baling hay and picking corn. Recognizing his son’s talent, Feller’s father, Bill, built a baseball diamond on the farm (reputedly the model for the ball field memorialized in W.P. Kinsella’s novel Shoeless Joe and the Kevin Costner film based on Kinsella’s novel, Field of Dreams)) and recruited other boys in the area to join his son on a makeshift team called the Oakviews. At age 17 Feller was signed by the Cleveland Indians and went straight to the majors; in the early 1950s he was the linchpin of one of the most formidable pitching staffs ever assembled, the legendary “Big Four” of Feller, Bob Lemon, Early Wynn and Mike Garcia. After retiring in 1956, Feller became an ambassador on multiple fronts: for baseball, for the Cleveland Indians, and not least of all for himself—when the Washington Nationals’ young phenom Stephen Strasborg made his major league debut with a blazing fastball this past summer, Feller was asked what he thought of the young phenom with the wicked heater. “Call me when he wins his one-hundredth game,” Feller replied.

In 1943 Feller married Virginia Winther, who died in 1981. He is survived by his three sons, Steve, Martin and Bruce.

Upon news of his passing, Feller was the subject of untold numbers of tributes by sportswriters across the country. Below are excerpts from three of the best online salutes to Feller, who wasn’t as black and white a human being as his fastball was swift but his athletic prowess combined with his complexity, his moral certainty and his fabled crankiness to make him a genuine larger than life figure.

Behold, a giant.

***

RIP Bob Feller

by Joe Posnanski, http://joeposnanski.si.com/2010/12/16/rip-bob-feller/?eref=sihp

(excerpts from column posted on December 16, 2010)One of my earliest memories was seeing Bob Feller in a jacket and tie. My father took me to some sort of morning meeting in Cleveland—a small room, in my memory, filled with metal folding chairs placed in uneven rows—and Bob Feller stood behind a lectern (and perhaps in front of a chalkboard; for some reason I see a chalkboard). I do not remember a single thing he said. I only remember him standing in the front of the room, and the awe he inspired, and my father telling me this: “That’s Bob Feller. He threw the ball faster than anyone who ever lived.”

The fastest pitcher ever. I was maybe five years old then, and the image shattered my imagination. This man in the suit? This man threw the fastest pitch ever? Of course, I believed it. Bob Feller was one of the enduring sports themes of my childhood in Cleveland, a sports childhood that was as fragile and brown as the autumn leaves dusting Cedar Road. My favorite teams were terrible. My favorite athletes were flawed. Cleveland’s past always seemed greener and richer and better than the future. I grew up on the story of Jim Brown pounding into the line, gaining five or six or seven yards, then lying on the mud and snow for what seemed forever (Is he hurt? Can Jim Brown BE hurt?). Then, finally, he would get up and jog back to the huddle, line up and pound back into the line, gaining five or six or seven yards again. I grew up on the story of Jesse Owens, who won gold medals under the outstretched arm of Hitler and then returned to Cleveland where people talked often about seeing him and meeting him and shaking his hand and how it felt like shaking the hand of history. I grew up on the stories of Paul Brown and Otto Graham and Rocky Colavito and Dante Lavelli (who, I was told, never once dropped a pass) and Lou Boudreau (who invented the Ted Williams shift).

Bob Feller's fastball is clocked using the Army Ordinance Dept.'s system for measuring artillery shell velocity. Rapid Robert's heater clocks in at 98.6 mph.Mostly, though, there was the legend of Bobby Feller, Rapid Robert, the Iowa farm boy who at age 17 took the mound at League Park in Cleveland, threw his hardest fastballs, and scared the living hell out of grizzled baseball men who thought they had seen it all.…

Bob Feller was always good for a quote. He had three qualities that made him so utterly quotable:

1. He saw the world in distinct and pronounced ways—Bob Feller was not much for shades of gray.

2. He did not mind telling you what he thought.

3. He did not seem to care much if people liked it.

Because of this, Feller was always good for a line about how pitchers were not as tough as they used to be or how much money is in the game or both. When all the hype about Stephen Strasburg built up in 2010, Feller was happy to pierce the absurdity of things (“Call me when he wins his 100th game”) or remind everyone that hype was not invented yesterday (“They broadcast my graduation from high school coast to coast, live on NBC”).

He said some things that followed him around all his life. Well that’s the cost of being quotable. And there was nothing easy about Bob Feller. He was, without question, the most famous ballplayer of his time who regularly barnstormed with black players. He and Satchel Paige were close, they were business partners, they were often great friends. And yet Feller said that Jackie Robinson would not make it as a big league player, and said that there wasn’t a Negro Leagues player who was good enough to play in the big leagues. (His famous and straightforward quote on the subject comes from 1969: “I don’t think baseball owes colored people anything. I don’t think colored people owe baseball anything either”). He railed against steroid users, the mushrooming of relief pitchers, the greed of owners, the greed of players and people who too quickly forgot their history. He offered up enough cranky quotes to leave an impression. He also said that the heroes of war are the ones who do not come back. And that America is the greatest country on earth. And that his father was the best man he had ever known.

Feller’s first start in the big leagues, he struck out 15. That was against the St. Louis Browns, who were managed by Rogers Hornsby—the man whose glove had helped set Feller’s baseball dream soaring. That game was in 1936, the day Jesse Owens returned home after winning those four Gold Medals at the Berlin Olympics. When the game ended, the home plate umpire Red Ormsby, who had been umpiring games since 1923, said simply: “That Feller showed more speed than I’ve ever seen uncorked by any American League pitcher, and that does not except Walter Johnson.”

That would be a common topic of discussion over the next 20 or so years as Bob Feller went through his Hall of Fame career. He did too many remarkable things as a pitcher to stuff into a single story. He led the American League in wins, innings and strikeouts every full year he pitched from 1939 through 1947. He threw an Opening Day no-hitter in Chicago in 1940, sparking what was always Feller’s favorite trivia question: “Name the only game in baseball history where every player on a team went into a regulation nine-inning game and came out of it with the same batting average.” That was Feller’s no-hitter. Each White Sox player came into the game hitting .000 and left hitting the same three digits.

He threw three no-hitters in all, one against the Yankees; he would sometimes call that his greatest day, though Feller had too many great days to stick with just one. That Yankees no-hitter was at Yankee Stadium in 1946 in what was probably Feller’s greatest year. He struck out 348 that season in what he thought was a modern major league record. It turned out that it was not the record—statisticians had miscounted Rube Waddell’s total from 1904 and upon recount it turned out he had 349. In any case, Feller won 26 games, and he threw 371 innings, and he proved that he was as good as ever after returning home from the war.

Bob Feller’s life and legacy: two reports from WEWS-TV NewsChannel5 in ClevelandAll the while, people tried to figure out how fast Feller threw. People often seemed more interested in that than his pitching greatness. He had his fastball tested many times. Once he was clocked at 104 mph. Another time, he remembered his fastball measured at 107.9 mph. He had his fastball measured by sensitive army equipment, and he had his fastball race against a motorcycle, and he had his fastball measured by various hard-throwing pitchers …

“If anybody threw that ball harder than Rapid Robert,” Satchel Paige said, “then the human eye couldn’t follow it.”

“Feller isn’t quite as fast as I was,” Walter Johnson said.

The second of those quotes is a bit surprising—Walter Johnson was a modest man who would often say that others (such as Smoky Joe Wood) threw harder than he did. But Johnson was nearing the end of his life when he gave that quote. Feller would later say that Koufax and Nolan Ryan didn’t throw as hard as he did. Maybe that’s age speaking. Maybe when you get older, you sometimes want to protect what you believe is yours.

Bob Feller, I suspect, always believed that he threw the fastest pitch in baseball history. He was generally pretty modest about it—his stock answer was that he belonged “in the discussion” but nobody could ever really know who threw the fastest. Still, I think he always believed that when he was just 17, when he came off the Iowa farm armed with his father’s pitching motion and the certainty of youth, he threw the fastest pitches that anyone has ever thrown.

Why do I think this? Well …

“Yes, I do think I threw a baseball harder than any man ever,” he told me once as we walked on a dirt field in Georgia. “A man should always believe in himself.”

***

I had finished interviewing him this one time—a typically rollicking interview that included stories and gripes and directions to the Bob Feller Museum, just 17 miles west of Des Moines. And for the first and only time, I told him that I was from Cleveland, and that one of my first memories was having seen him speak.

And then Bob Feller asked me about my father. Direct questions. Did he play catch with me when I was young? I said yes. Did he take me to baseball games? I said yes. Did he believe in me deeply? I said yes.

The tape recorder was off and my notebook was put away and so I cannot write here what he said word for word. But I remember the important part. He told me that I was lucky, that what you need to succeed in this world is a father who believes in you. And he told me that his father believed in him. Funny thing, though, he said Bill Feller never once said, “Bob, someday you’re going to pitch in the big leagues.” No, there were no words. There are some things that cannot be said with words. There was only those sweaty Iowa afternoons and those chilly Iowa evenings, and the sun setting, and a baseball going back and forth. Everything he needed to know about life was in that back-and-forth.

Bill Feller died in 1943, while his son Bob was at war. He had seen his son become the best pitcher in baseball.

A terrific interview with Bob Feller in 1990, by the late Nev Chandler of WEWS Live at Five. In discussing the four years of his career lost to service in World War II, Feller says: ‘As far as I’m concerned I’m no hero. The heroes didn’t return to this country. They’re in Europe, they’re in the bottom of the Pacific and on the islands in the Pacific. I came back and had a career.’***

Bob Feller aboard the USS Alabama in World War II. He was awarded with five campaign ribbons and eight battle stars.Remembering Rapid Robert

by Scott at wfny.com (Waiting For Next Year), full text at http://www.waitingfornextyear.com/?p=37923

Bob Feller died Thursday in Cleveland of acute leukemia. He was 92 years old. He grew up on a farm in Iowa. He played catch with his Dad. He played baseball for the Cleveland Indians when he was young. And when he was no longer young, he traveled the country promoting baseball and himself and America and all the things he believed in deeply. He signed more autographs, probably, than any man in baseball history—so many that an autograph dealer once joked that a baseball without Feller’s autograph was rarer and more valuable than one with. Bob Feller leaves behind family, friends, a detailed baseball record, countless stories and little confusion about how he felt about things. And he threw a baseball harder than any man who ever lived. At least that’s what my father told me.

Yet when all was said and done, Feller did not run off to the bright lights of a bigger city. Not only did he spend his entire career with the Cleveland Indians epitomizing loyalty, Bullet Bob was present for approximately 75 straight opening days in Cleveland and was immensely active in various Tribe-related fundraisers and camps.

When the worst thing one can say about a man is that he was “brutally honest,” it’s safe to say that he was cherished by all who had the fortuitous opportunity to cross his path.

In a day in age where we tend to talk about player “brands” and Q-Scores, Feller cared more about his country, his sport and his team. By now, you’ve all heard the stories: Feller sacrificed four years of his baseball prime to join the Navy, enlisting the day after the Pearl Harbor attacks; he was instrumental in the inception of what is now the players union; he skipped the minor leagues all together and put up numbers that will likely never be broken by a member of the Cleveland Indians. Ever.

The one thing that Bob Feller did not get to see was another Indians championship—something which he had longed for since the day of his retirement. It was recently recommended that the Indians should forgo a ceremonial first pitch during the 2011 opening day. Given that the man who should be throwing it is no longer with us, I defy one to think of a better way to start the next chapter of Cleveland Indians baseball.

***

‘Cleveland Indians, eh? Feller pitching?’ ‘Of course there’s a feller pitching. Whatta think, they’d use a girl?’ Bud Abbott tries to explain Bob Feller to Lou Costello in a skit that evolved into the duo’s classic ‘Who’s On First’ bit.***

‘One Of These Days It Will Be The Last First Pitch’

Anthony Castrovince, who writes the CastroTurf blog for MLB.com, penned the following thoughts about Bob Feller upon learning that the fireballing legend had been transferred to hospice care. The complete column is at http://castrovince.mlblogs.com/archives/2010/12/that_attitudes_a_power_stronge.htmlIt was in the summer of 2007 that I got to know Feller on a deeper level. The Indians invited me to come along on a chartered flight to Des Moines. They had arranged for the filming of a documentary on Feller's Iowa upbringing, and Feller was aboard to show the camera crew his roots. I'll never forget that trip. It was better than any American history course I could have taken in college. Feller showed us the farm where he formed his fastball and the cornfield that he and his father turned into a baseball field. He took us to his museum, which was, to him, a great source of pride, and to the street that bears his name.

My favorite stop of the tour might have Booneville, Iowa — a tiny town that, by my recollection, contained a couple grain silos, a small diner, a few houses and, well, not much else. But there was a building where a bank once stood, and Feller shared with us a story passed down to him by his father. It seems the bank's owner lived across the street, and one day at lunch he looked across the street into his bank to see it being robbed by three crooks. The bank owner grabbed his gun and shot each crook dead on the spot as the exited.

Feller loved this story. "Instant justice," he said.

‘He was perfectly willing to gamble on himself’—Bill Veeck recalls the ‘unusual’ contract negotiations he engaged in with Bob FellerBut another memory I have of that trip—the memory I'll take with me long after Feller is gone— is of the visit we made to the house he built for his parents at the site of the farm. The house is now inhabited by a local doctor and his family, and Feller's frequent visits have made him a grandfather-type figure to those kids. When we arrived, they all excitedly greeted him with hugs and tagged along as he visited the red barn where he used to play catch with his dad.

"Decide what you really want to do early in life, then do it," Feller told those kids. "Then you never have to work a day in your life. That's what I did. I played ball for a living."

In the wake of last night's news that Feller has been transferred to hospice care, I find myself instinctively writing about him in the past tense. It's not intentional; it's just that we all knew a day would come when Feller, 92, would begin to succumb to Father Time, and that day, sadly, appears to be close. Feller, of course, acknowledged as much earlier this year, when he talked about throwing out a ceremonial first pitch at a Spring Training game.

"One of these days," Feller said with a smile, "it will be the last first pitch."

***

‘A Giant Of A Man’

Walt Dropo

January 30,1923-December 17, 2010

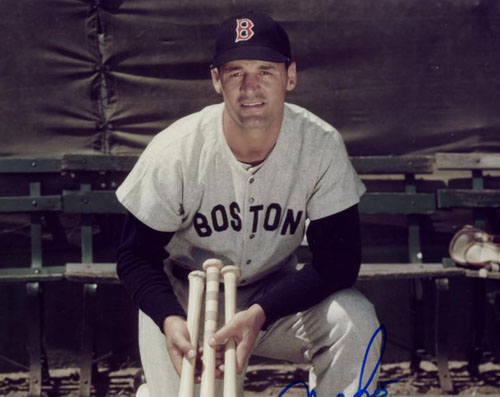

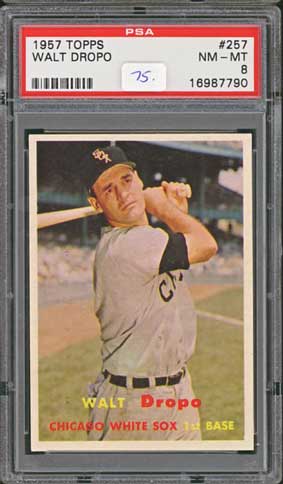

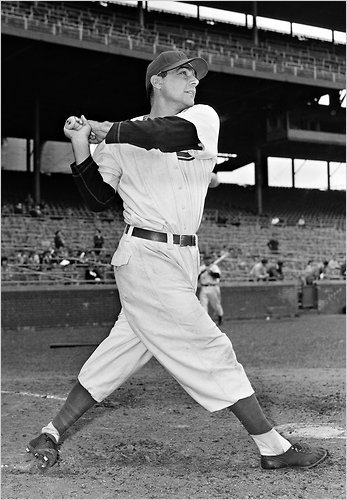

When 1950 American League Rookie of the Year Walt Dropo passed away from undisclosed causes on December 17, 2010, most obituaries made fleeting references to a storied three-sport collegiate career at the University of Connecticut and concentrated on his achievements over the course of a 13-year major league career spent with the Boston Red Sox (1949-1952), Detroit Tigers (1952-1954), Chicago White Sox (1955-1958), the Cincinnati Reds (1958-1959) and the Baltimore Orioles (1959-1961). In June 1952, shortly after joining the Tigers, he stroked 12 consecutive hits to set a major league record, and tied another record by totaling 15 base hits in a four-game span. Both records still stand.

The University of Connecticut, however, made sure to recognize “the greatest three-sport star” in its athletic history, with a comprehensive tribute to both his collegiate and professional tenures. Posted on December 18 at www.uconnhuskies.com, it simply cannot be improved upon, and is reprinted here in memory of a fine athlete and a good man.

UConn Legend Walt Dropo Passes Away

Was a three-sport star for the Huskies and 1950 AL Rookie of the year

Dec. 18, 2010

STORRS, Conn.—Walter (Moose) Dropo, 87, recognized as the greatest three-sports star in University of Connecticut athletic history, died Friday, Dec. 17.

Dropo, affectionately known as the "Moose from Moosup", was born in Moosup, Conn., on January 30, 1923 to the late Mary and Savo Dropo. Dropo attended Plainfield High School graduating in 1941, winning athletic letters in football, baseball, basketball and track.

He attended the University of Connecticut the following fall and remained there until 1943 when he entered the Army. He saw service as a combat engineer in Africa, Italy, France and Germany.

Dropo played football, basketball and baseball for UConn with his college career interrupted by three years of military service.

Dropo completed his college career in 1946-47 as Connecticut's all-time leading scorer in basketball and more than 60 years later still ranks No. 2 all-time at UConn in career scoring average at 20.7 per game. He was a two-time All-New England selection at UConn and also starred on the school's football and baseball teams.

"Walt Dropo was the forerunner of all the great student-athletes we have had here at UConn," says Dee Rowe, UConn's Special Adviser for Athletics. "Wherever he went, he had UConn on his jersey. People around the country knew of UConn because of Walt Dropo. If Walt was here today, he would be talking about how the football team was going to the Fiesta Bowl, the national rankings of the men's and women's basketball team and going to the NCAA baseball tournament last year.

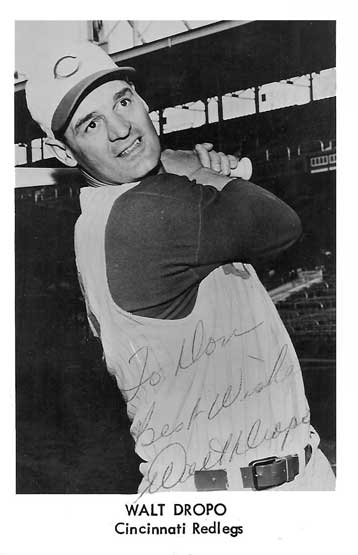

"He was a giant of a man and very proud of his family and heritage. When he walked into a room, he had has this great presence. You knew he was there and he just captured everyone."

Dropo was one of three brothers who traveled from Moosup to the UConn campus—-joining brothers Milton and George as athletic stars at Connecticut. Following their graduations, the Dropo brothers were lifelong major benefactors to their alma mater, including establishing the first fully endowed athletic scholarship at Connecticut and being acknowledged as "The First Family of UConn Athletics."

Walt Dropo as a Cincinnati Red: ‘When he walked into a room, he had has this great presence. You knew he was there and he just captured everyone.’"There is not a baseball player on the UConn team that doesn't learn about the Dropo family's contribution to our program and our University," says current Husky baseball coach Jim Penders. "I am glad I had the pleasure to know Walt and will never forget the first time I shook hands with him when I was a UConn freshman. He said `Ted always told me to meet the ball, just meet the ball' and he was referring to his teammate Ted Williams. We were in awe. Our condolences go out to the Dropo family and I bet there are three brothers having a heck of a game of pepper today."

"Walt and his family were very giving people," said Andy Baylock, UConn's former baseball coach (1980-2003), who now serves as the Director of Community and Alumni Development for the Husky football program. "They would do anything for UConn. The three brothers were so close and whenever they came to campus it was very special."

Walt Dropo was a first round draft pick of the Providence Steamrollers (fourth overall pick) in the 1947 pro basketball draft (UConn's first "lottery" pick) and was also drafted as an end in the ninth round of the 1946 NFL Draft by the Chicago Bears.

Despite those two professional opportunities, Walt Dropo signed a professional baseball amateur free agent contract with the Boston Red Sox in 1947.

He played in minor leagues starting in 1947 with stops in Scranton of the Eastern League (1947), Birmingham of the Southern League and Louisville of the American Association (1948), Sacramento of the Pacific Coast League (1949). He is a 2007 inductee into the Birmingham Barons Hall of Fame. He led the team to a Dixie Series victory over the Forth Panthers by hitting a co-team-high .359. That mark is still the ninth-highest average recorded by a Barons player in a single season. Among his many Barons highlights was one of the longest home runs at historic Rickwood Field, hit in that same Dixie Series: a 467-foot blast memorialized with a permanent plaque at the field behind the left-centerfield wall.

In 1950, as a 27-year-old rookie first baseman with the Red Sox, Dropo enjoyed one of the greatest rookie seasons in major league history, leading the American League in runs batted in (144) and total bases (326) while batting .322 and hitting 34 home runs. He was second in the AL in home runs, slugging percentage (.583), and extra base hits (70).

Dropo's 1950 season saw him become baseball's first-ever rookie to top 100 RBIs with more RBIs than games played (144 RBI in 136 games).

Walt Dropo became the first Boston Red Sox player ever named American League Rookie of the Year (topping New York Yankee pitcher Whitey Ford in the rookie voting) and he finished sixth in voting for the AL's Most Valuable Player. He was also named to the American League All-Star squad.

A fractured right wrist slowed Dropo's career in 1951 and he never was able to match the remarkable exploits of 1950 during the remainder of his lengthy 13-year major league career.

"Walt Dropo was one of the greatest players the Red Sox had in the post-World War II era," said Dick Bresciani, the Vice President/Publications and Archives for the Boston Red Sox. "He was an outstanding gentleman and did a lot of good things for our organization in the community when his playing days were over. The Red Sox send their condolences to his family."

In 1952, shortly after being traded from the Red Sox to the Detroit Tigers, Walt Dropo tied a major league record that still stands today when he collected 12 hits in consecutive trips to the plate and during that hitting streak he also tied another major league record that is still in place today when he totaled 15 base hits in a four-game span.

In his 13-year major league career, Walt Dropo hit .270, playing in 1,288 games for the Boston Red Sox (1949-52), Detroit Tigers (1952-54), Chicago White Sox (1955-58), Cincinnati Redlegs (1958-59) and the Chicago White Sox (1959-61).

Walt Dropo has repeatedly been honored by his college alma mater.

In 1969, he was a member of an 11-member All-Time football team named by UConn during a celebration of the 100th anniversary of college football. In 1998, Walt Dropo was named to UConn's 100th Anniversary of Connecticut Football All-Time Team.

In 2001, Walt was honored as a member of UConn Basketball's All-Century Team and in 2006 Walt Dropo was part of UConn Basketball's inaugural class of inductees to Connecticut's Huskies of Honor—a program that pays visible tribute in the Harry A. Gampel Pavilion to the top players in UConn basketball history.

Walt Dropo as a Chicago White Sox first basemanIn 1951, he had married Elizabeth Wise and together they had three children, Jeffrey, Carla, and Christina. Sadly, Jeffrey passed away in 2008 after a two-year journey with brain cancer. The Dropos made their home in Marblehead, Mass., as Dropo began careers in the financial services industry and then in the import-export business dealing primarily with fireworks. He was passionate about supporting UConn athletics, keeping a strong connection to his Serbian heritage through his affiliation with St. Sava Serbian Orthodox Church, and spending many long, enjoyable days golfing at celebrity golf tournaments and with his friends at the Portsmouth Country Club.

Dropo is survived by Elizabeth, his daughters, Carla and her husband Tom Welch of Beverly, Christina and her husband Vladian Hogea of California, and a daughter-in-law Susan Dropo of Sandwich. Carla Dropo is a 1980 UConn graduate and was a student-athlete in women's swimming. She served as a team captain her senior year and worked in the UConn Athletic Development Office.

He is also survived by two sisters, Emily and her husband Roger Harrington of Dayville, Conn., and Zurka Alfieri of Groton, Conn. He was predeceased by his beloved son Jeffrey, brothers Milton and George, and brother-in-law Nicholas Alfieri. Walter also has five grandchildren Jennifer, Elizabeth, and Alexander Dropo of Sandwich, Mass., and Sarah and Nicole Welch of Beverly, Mass., four nieces, Cindy Alfieri of New Jersey, Joanne Alfieri and her husband Eric Wolfe of Connecticut, and Sandy and Dianne Wise of Seattle, Wash., three nephews, Carl of Dayville, Connecticut and Paul Harrington of Brooklyn, Conn., William Wise of Alaska and a grand nephew, Nolan Harrington.

Contributions may be made in Dropos's name to the National Brain Tumor Society, 124 Watertown Street, Suite 2D, Watertown, MA 02472, or the Jimmy Fund, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, 10 Brookline Place West, 6th Floor, Brookline MA 02445.

***

‘A Heck Of A Hitter. Just Look It Up.’

Phil Cavarretta

July 19, 1916-December 18, 2010

Phil Cavaretta, who holds the Chicago Cubs’ record for longevity with 20 seasons and is believed to be the last living player to have played against Babe Ruth. died on December 18, 2010 in a hospice care center in Lilburn, GA. He had suffered a stroke several days earlier.

On September 25, 1934, only two months removed from his 18th birthday, Phil Cavaretta made his first start as the Chicago Cubs’ first baseman. In 1953 he played his last game as a Cub, breaking Stan Hack’s team record of 1,938 games (a mark later surpassed by Ernie Banks in 1966). In his 22-year major league career, Cavaretta compiled a .293 batting average with 95 home runs and 920 RBI. In all, he spent nearly 50 years in baseball as a player, coach, manager and scout and was known for being gracious with fans requesting his autograph.

Signing with the Cubs in 1934 before completing his education at Lane Tech High School in Chicago (located only a mile from Wrigley Field), the 17-year-old Cavaretta played his first pro game (as a right fielder) with Peoria and hit for the cycle. His first major league appearance with the Cubs came on September 16, 1934, when he pinch-hit for Cubs’ shortstop Billy Jurges. In his first start a week later, he hit a game winning home run in 1-0 win over Cincinnati at Wrigley Field. In his 1935 rookie season he hit .275 with 82 runs batted and led the league in double plays. The team went on a 21-game winning streak in the last month of the season to capture its third pennant in seven years, but lost to the Detroit Tigers in the World Series, with Cavaretta hitting only .125. Cavaretta became a reliable first baseman (and backup outfielder), hitting anywhere from .270 to .294 in all but one season through 1943. In the 1938 World Series against the New York Yankees, the Cubs were swept four games to none, but Cavaretta logged a scorching .462 batting average.

Cavaretta had his most productive years in the mid-‘40s: in ’44 he hit .321, notched career highs in runs (106), doubles (35) and triples (15) and had a league leading 197 hits and earned his first of his four straight All-Star team selections. The 1945 season was even better for Cavaretta and for the Cubs: in an MVP year, Cavaretta led the league in batting average (.355) and on-base percentage (.449), drove in 97 runs and finished third in slugging percentage (.55); the Cubs improved from a horrid 1934 season to edge the defending champion St. Louis Cardinals for a trip to the World Series, where the Detroit Tigers prevailed in seven games, although Cavaretta again excelled on baseball’s biggest stage, with a .423 batting average, .500 on-base percentage and .615 slugging percentage. He scored seven runs, had 11 hits and drove in five runs. His career batting average in three World Series was .317, with a .413 slugging percentage. His playing time gradually diminished after the 1949 season, his last season of appearing in more than 100 games, but he had strong campaigns at the plate in 1951 (.311 BA in 89 games) and in 1954 (.316 BA in 71 games). In 1951 he was named manager of the Cubs, succeeding Frankie Frisch, and helmed the team for the two succeeding seasons, with a record of 169-213. After being fired by the Cubs in spring training in 1954 (he signed his pink slip by telling team owner P.K. Wrigley that the Cubs were probably a fifth place team; actually, they turned out to be a seventh-place team), but went crosstown and signed with the Chicago White Sox, retiring after the 1955 season. He stayed in the game as scout and, starting in 1973, a hitting instructor for the Mets, hired by his former Cubs teammate Bob Scheffing, then the Mets' general manager.

In a statement released through Dave Kaplan of the Yogi Berra Museum and Learning Center, the Yankees great recalled Cavaretta, whom Berra worked with as a Mets hitting instructor when Berra managed the Mets, as “a heck of a hitter, just look it up. Bob Scheffing (the New York Mets GM) knew him well, they played on the Cubs together and brought him in as an instructor. Phil was good, he knew hitting and was a good help to us. I remember him as a good baseball man and a nice fellow."

Jack Heidemann was an infielder with the Mets during the 1975 season trying to find his place back in the majors after suffering a major knee injury a few years earlier. As a fellow infielder, Cavaretta took a liking to him right away. "I came over from St. Louis and he helped me in spring training that year. I was still a young guy then, I was coming off a pretty good year with St. Louis and I had a knee operation in St. Louis that sent me back to the minors for two years after Bobby Murcer took me out in Cleveland. I was coming in and he took me under his wing. He liked me because I was an infielder too."

Heidemann described Cavarretta's style as reserved. "He was like Alvin Dark, very low key, but not a manager or coach that would just go ballistic like a Earl Weaver. 'Cavvy' could give you the look now, but he didn't show you up. He was to the point but he wasn't a rah-rah guy. He expected you to do your job and that was it. He wasn't somebody who would pull you by the side and say, 'Hey you've gotta do this and you've gotta do that.' He never downgraded, it was always, 'You can do better or try this, try that, etc..'"

Phil Cavaretta is survived by his wife, Loraine, four daughters and one son.

***

‘It Was No Fun To Hit Against Him’

Ryne Duren

February 22, 1929-January 6, 2010

Ryne Duren had a blazing fastball, erratic control and wore a blind man’s dark glasses, thick as Coke bottles, as the saying goes. It was always an event when he came in from the New York Yankees’ bullpen, simply owing to the unpredictability of what would happen next. The tragic story of the Cleveland Indians’ Ray Chapman, who died after being struck in the head with a pitch in a game against the Yankees in 1920, was never far from memory when Duren took the mound and the first batter to face him stepped into the box. Duren was famous, too, for enhancing his intimidation factor by launching a warmup pitch well over his catcher’s head into the backstop while the hitter in waiting contemplated the task ahead. Duren’s tragic flaw of wildness prevented him from piling up daunting statistics and being considered among the great relievers of his generation, but that didn’t keep baseball fans from regarding him with a certain awe, of viewing him as a legend. After he retired, Duren would return to Yankee Stadium for Old Timer’s Games, where, to the roar of the crowd, he would heave a pitch into the stands.

“Ryne could throw the heck out of the ball,” said Yankees’ great Yogi Berra, who was one of those catchers Duren overthrew during warmups. “He threw fear in some hitters. I remember he had several pair of glasses, but it didn’t seem like he saw good in any of them. He added a lot of life to the Yankees and it was sad his drinking shortened his career.”

Ryne Duren died on November 6 at his winter home in Lake Wales, Florida. He was 81.

In comments to the Associated Press, Yankees second baseman Bobby Richardson called Duren “a legend,” and added: “It was no fun to hit against him. Everyone was afraid he was going to hit them.”

Richardson figured in one of the classic Duren stories, in fact. In a game against the Angels, with Duren pitching, Richardson noticed the catcher making lazy throws back to the mound. In between pitches, he took off and stole third without drawing a throw. Duren approached Richardson at third and promised he would throw a pitch at the Yankee second baseman the next time he faced him.

Mickey Mantle came to the rescue, as Richardson recalled. “Mickey took Ryne out drinking that night and calmed him down. I saw Mickey later and he said, ‘You’re all right, he’s not going to hit you.'"

Duren played for seven teams during a big league career from 1954 to 1965. His career stats are unimposing: 27-44 won-loss record, 3.83 earned run average, 630 strikeouts, 392 walks in 589 1/3 innings encompassing 311 mound appearances. He threw 38 wild pitches. He led the American League with 20 saves for the Yankees in 1958, and in the ’58 World Series pitched a strong 4 2/3-inning stretch in Game 6. “I had the ball in the fifth inning and was still there in the 10th,” Duren told Baseball Digest in 2004. “If you’re talking about th game’s importance, that ’58 Series was certainly the highlight of my career.”

In five World Series appearances he was 1-1 with a 2.03 ERA. He broke into the majors with Baltimore in 1954, played for Kansas City in 1957, was traded to the Yankees in 1958 and remained in pinstripes through 1960, then bounced from the Los Angeles Angels (1961) to Cincinnati (1964) to Philadelphia (1963-64, 1964) to the Washington Senators (1965) before retiring. Born Rinold George Duren in Cazenovia, WI, he was a high school baseball star with a fastball to swift his coaches often had him play infield rather than risk him beaning an opposing player with one of his fastballs.

After retiring, Duren wrote two books, I Can See Clearly Now and The Comeback, in which he revealed and spoke frankly about his drinking problem and how it had affected his career and his off-field life. Behind the scenes he worked diligently to counsel players about the dangers of alcohol and drugs. In 1986 he testified in New York at a state Assembly hearing that was considering a bill requiring an alcohol-free zone at sporting events with 250 ore more spectators. “He helped so many former players, counseling them and doing follow-up work,” Richardson said. “He really made a difference in so many lives.”

Among Duren’s survivors is his stepson, Mark Jackson, and his nephew Blackie Lawless, of the heavy metal band W.A.S.P. —David McGee

From Rinold To Ryne To Legend: What’s In A Name?

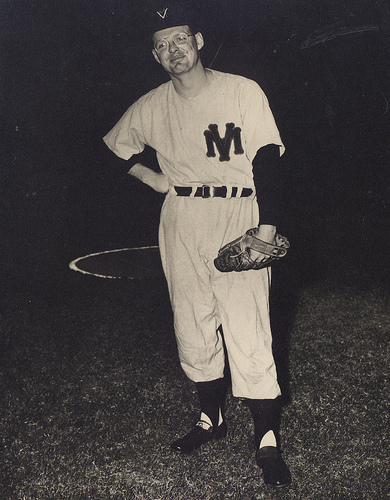

Ryne Duren as a Vancouver Mountie in 1956. He posted an 11-11 won-loss record, 4.11 ERA and struck out 183 in 205 inning.Only two major league players ever sported the name Ryne—Ryne Duren and Cubs Hall of Fame second baseman Ryne Sandberg (thanks to the latter’s popularity, seven other minor league Rynes have played the game as well).

To Duren, though, it was all an accident, his unique Christian name. “I didn’t like being Junior,” he told Daily Pitch http://www.youtube.com/user/marthahreid reporter Paul White in May 2010.

As per White’s report: Duren was born Rinold George Duren on Feb. 22, 1929 in Cazenovia, Wis. The middle name comes from sharing a birthday with George Washington, Duren says, but his first name came from his father, who was born Rheinold Nicholas Duren to a very traditional German family.

His dad's spelling got changed over the years and that's the name the younger Duren received. But everyone in Cazenovia called him Junior—and they still do during the half of the year he spends there. Duren splits time between Wisconsin and Florida and still travels for card shows and speaking engagements to spread his message of the dangers of alcohol, a problem he dealt with during his playing career (1954-65).

"After high school, I went to business college in Rockford, Illinois,' Duren says. "My friends and I were talking about how I didn't like Junior and what I should be called. We decided on Rine, but they said, 'You ought to spell it Ryne.' I liked that."

So, that's who he was when he debuted as a pro in 1949 with Wausau, about 90 miles from his hometown, in the Class D Wisconsin State League. And he was still Ryne when Sandberg's parents, in Spokane, Wash., heard his name 10 years later during a Yankees telecast.

***

At press time, February 13 is listed as the earliest day for pitchers and catches to report to spring training.

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024