'I Find The Goodness In People'

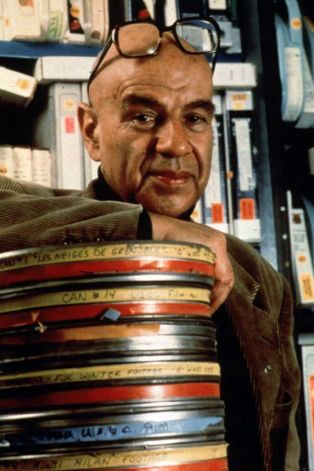

Bud Greenspan

September 18, 1926-December 25, 2010

Once was the time when Olympic athletes were considered to have triumphed by entering the arena. The athletes themselves still seem well aware of their achievement being measured not in medals only, but rather in competing, in rising to the top level of the world's athletes and performing to the best of their ability. That the mainstream media focuses at all on the human stories of Olympic athletes, rather than the medal chase alone, is a tribute to the lasting influence of one man—filmmaker Bud Greenspan, who as a radio reporter filed his first Olympic story from a phone booth at Wembley stadium during the 1948 London Games and was working on a documentary about the 2010 Vancouver Games when he died at his home in New York City on Christmas Day, from complications of Parkinson's disease. He was 84.

As the Olympics became both more commercial and more politicized, Greenspan was sometimes criticized for focusing on feel-good stories rather than more nettlesome issues reflected in competition between athletes representing countries with troubling political and human rights issues, or, more recently, when the use of performance enhancing drugs has tainted almost all competitive sports. Paying no mind to his critics, Greenspan, his large, black-rimmed glasses resting on his shaved head, was sure of his purpose as he prowled around the arenas and fields at the Games, and evinced no concern for how others characterized his work. From the time he filmed his first Olympic competitor in action—U.S. gold medal winning weightlifter John Davis, with whom Greenspan had worked as a non-singing extra at the Metropolitan Opera, at the 1952 Helsinki Game—Greenspan was after the human stories otherwise overlooked in the breathless cataloguing of medal pursuits, particularly when those stories were profiles in courage, resilience and valor of an uncommon degree.

"I choose to concentrate one hundred percent of my time on the ninety percent of the Olympics that is good," he once told ESPN.com when asked about critics of his approach. "I've been criticized for seeing things through rose-colored glasses, but the percentages are with me. I find the goodness in people, and I present them as people first and athletes second.

"People don't pay enough attention to those who come in fourth, seventh or tenth. It amazes me every time that someone can lose by a fraction of a second and no one pays attention to them."

From Bud Greenspan's 16 Days of Glory, a documentary of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games, the story of British runner Dave Moorcroft, a winner despite finishing last in the 5000 meter race, as only Bud Greenspan could tell it, in a story completely ignored by the mainstream media. Greenspan cited Moorcroft's story as one of his favorite Olympic tales.

Starting with the 1984 Summer Games in Los Angeles, Greenspan was the official Olympic filmmaker seven times, including at the Summer Games in Atlanta (1966) and Sydney (2000), and the Winter Games in Calgary (1988), Lillehammer (1994), Nagano (1998) and 2002 (Salt Lake City). When he was not designated as official Olympics documentarian, he worked independently, as was his preference. His style was to let the athletes tell their stories, in interviews conducted before and after the events, and in live action footage edited seamlessly from multiple days of competition, with an absolute minimum of narrative voiceover—Greenspan's words—providing the context and dramatic backdrop for what unfolds before the cameras.

As noted by Mike Kupper in an obituary of Greenspan published on December 26, 2010 in the Los Angeles Times, Greenspan was especially drawn to stories of inspiring athletic perseverance, as exemplified in two human dramas he was especially moved by—those of Tanzanian marathoner John Steven Aquari and British distance runner Dave Moorcroft.

From Kupper's account:

In the 1968 Mexico City Games, Aquari was the last man to finish the long race, hobbling into the darkening stadium more than an hour after the early finishers, his right leg bleeding and hastily bandaged, completing the marathon to the cheers of what few fans were left. Asked later by Greenspan why he had continued running, Aquari answered, "My country did not send me 5,000 miles to start the race. My country sent me 5,000 miles to finish the race."

Moorcroft entered the 5,000-meter run in Los Angeles as the world-record holder, but also having recently suffered a stress fracture in his leg, a bout with hepatitis and a pelvic problem that interfered with his stride. He quickly fell off the pace and into last place, sprinting in ungainly fashion to keep from being lapped as the race ended. When Greenspan asked Moorcroft later why he had not quit, the runner replied, "Once you quit, it's easy to do it again. I did not want to set a precedent for the future."

Asked by ESPN.com to name his favorite Olympic moment, Greenspan immediately singled out the last-place finish of Tanzanian marathoner John Stephen Ahkwari at Mexico City in 1968.

"He came in about an hour and a half after the winner. He was practically carrying his leg, it was so bloodied and bandaged," Greenspan recalled in that ESPN.com interview. "I asked him, 'Why did you keep going?' He said, 'You don't understand. My country did not send me 5,000 miles to start a race, they sent me to finish it.' That sent chills down my spine and I've always remembered it."

In his career Greenspan won eight Emmy awards and a George Foser Peabody Award for "distinguished and meritorious public service"; received the Olympic Order, the International Olympic Committee's highest honor; and in 2004 was inducted into the United States Olympic Hall of Fame as a special contributor. From the Directors Guild of America and the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences he received lifetime achievement awards

Greenspan first made his mark in Olympic history with his 1964 film Jesse Owens Returns To Berlin, documenting Owens's pilgrimage to the scene of his gold-medal achievements in Berlin some 30 years earlier, when his triumph over elite German athletes had infuriated Adolf Hitler, whose idea of a master race was lily white and Anglo Saxon. The Owens film was later included as a chapter in a 22-hour-long Emmy winning documentary on the Olympics, The Olympiad.

Jesse Owens Returns To Berlin—the opening scene of Bud Greenspan's 1964 chronicle of the U.S Olympian's return to the scene of his 1936 triumphBorn Jonah J. Greenspan on Sept. 18, 1926, in New York City, he was afflicted with a lisp, an impediment he cured himself as he focused his adolescent dreams on a career in radio. By the age of 21 he had graduated from New York University and become sports director at New York's WMGM-AM, then the largest sports station in the country. As a print journalist, he logged time as a sportswriter, then moved into TV, initially as a reporter, later as a producer. He wrote books (several about the Olympics as well as a book of sports bloopers and sports controversies) and produced 19 spoken-word albums including the certified Gold long player, Great Moments In Sports. Despite his struggles with Parkinson's, he maintained an active work and travel schedule in his later years.

After spending $5,000 of his own money to produce his film on weightlifter John Davis in 1952 (The Strongest Man In The World), Greenspan found a buyer for it—to the tune of $35,000—in the U.S. State Department, which viewed its portrait of an accomplished African-American as a means to thwart Korean War-era Soviet propaganda about American racism. Said Greenspan to the L.A. Times in 1999: "I thought, This is good business."

With his wife Constance Anne "Cappy" Petrash, Greenspan formed Cappy Productions and continued producing with her the feature-length sports films he had been marketing since the early '60s. "Cappy was a non-fan, but her outlook was perfect for the kind of thing we were doing," Greenspan told the Wall Street Journal in 1988. "She'd ask our subjects what books they read or whether they cooked, and the answers usually turned out to be wonderful. They gave our work a dimension others lacked."

Cappy died of cancer in 1983, a year before Greenspan's first Games as official documentarian. Recalled Greenspan, "We didn't have children and she would say, 'The films will be our kids. They'll live long after we're here.' And that, in a sense, is immortality, and that is exactly what I think we're here for, to leave something for this generation and generations not yet born."

'And so the long journey of Yasuhiro Yamashita is over, and with it a fulfillment of the philosophy of judo: yielding is strength; gentle turns away sturdy." A moving chapter from Bud Greenspan's 16 Days of Glory: the story of the final match of the great Japanese judo master Yasuhiro Yamashita, who came into the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games with a seven-year unbeaten streak. A quintessential Bud Greenspan moment.Greenspan later hired Nancy Beffa to work with him, and she eventually became his business partner and companion. "His legacy, really, is his films. He wanted them to live on, to illuminate what was good about people," Beffa said. "Bud was a storyteller first and foremost. He never lost his sense of wonder and he never wavered in the stories he wanted to tell, nor how he told them. No schmaltzy music, no fog machines, none of that. He wanted to show why athletes endured what they did and how they accomplished what so few people ever do."

Mike Moran, a former U.S. Olympic Committee spokesman, saw Greenspan's legacy in the larger framework of the Games' historical sweep. "Greenspan's lifetime of work was to the Olympic Games and the athletes what John Ford's cinema was to the American West. He had no peer in his craft, and he was the artist that thousands of Olympic athletes dreamed of when they thought of how their stories might be told one day."

Scott Blackmun, the USOC's chief executive officer, lauded the filmmaker for connecting the games to "everyday people in ways the founders of the games couldn't have imagined."

Typical of his focus on profiling the underreported stories at events he was chronicling, Greenspan presented one of his most important films in 2007. Pride Against Prejudice—The Larry Doby Story documents the unsung power hitting Cleveland Indians outfielder Larry Doby, who followed (by 11 weeks) Jackie Robinson in integrating Major League Baseball and battled the same adversity and prejudices as Robinson and, like Robinson, well earned his induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame at Cooperstown.

Besides Beffa, Greenspan is survived by a sister, Sarah Rosenberg. The family has requested that any donations be made to a scholarship in his name administered by the USOC at the University of Southern California film school.—David McGee

***

Priceless Moments from Bud Greenspan's 16 Days of Glory, his documentary of the 1984 Los Angeles Games

16 Days of Glory—Women’s High Jump, Part 1. Two gold medalists compete for the women’s high jump title. 1972 champion Ulrike Meyfarth (West Germany) and 1980 champion Sara Simeoni (Italy). Copyright 1985 Bud Greenspan and IOC.

16 Days of Glory—Women’s High Jump, Part 2. Two gold medalists compete for the women’s high jump title. 1972 champion Ulrike Meyfarth (West Germany) and 1980 champion Sara Simeoni (Italy). Copyright 1985 Bud Greenspan and IOC.

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024