‘You Say I’m What?’

The Resounding Statement Of The Complete Elvis Presley Masters

By David McGee

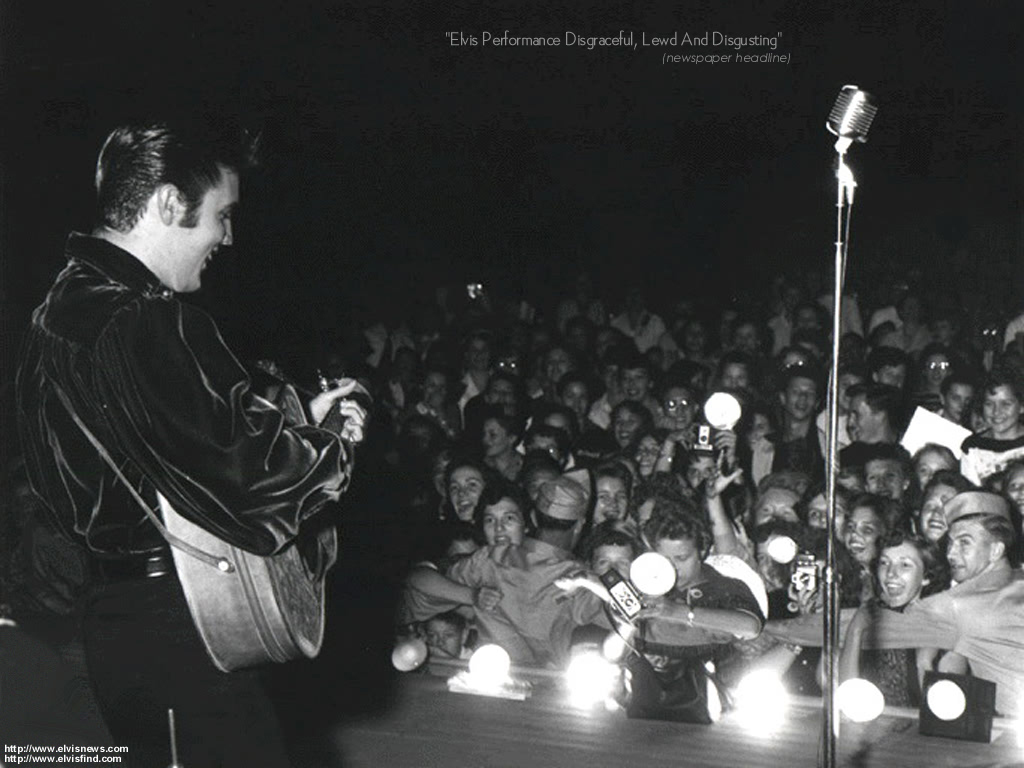

Let’s face it: our man Elvis is under siege, and has been for some time. I speak not of the furor he aroused upon his hip swiveling emergence in the mid-‘50s but of more recent assaults on his character and legacy.

It started in 1990, when the mentally challenged Chuck D of Public Enemy declared of Elvis: “straight-up racist that sucker was, simple and plain.” Some years later on VH1’s Divas Live, the flatlining Mary J. Blige offered the My Lai defense after performing “Blue Suede Shoes,” saying, “I prayed about it (performing the song) because I know Elvis was a racist. But that was just a song VH1 asked me to sing. It meant nothing to me. I didn't wear an Elvis flag. I didn't represent Elvis that day. I was just doing my job like everybody else.” (Quote from “Elvis Presley and Racism: The Ultimate, Definitive Guide,” published January 2, 2011 in Elvis Australia). (Here’s a question for Ms. Blige: Since Carl Perkins wrote “Blue Suede Shoes” and learned his first guitar chords from an elderly black man who picked cotton in the same field as the Perkins family in Tiptonville, TN, is he a racist too? He was a close friend of Elvis’s to boot. The conspiracy widens and the mind reels.)

Much like Republicans who were for something before they were against it, Chuck D has walked back, somewhat, his fact-free charge against Elvis, but Peter Guralnick, author of the definitive biography of Elvis (in two volumes), put Mr. D gently in his place and undercut the whole “Elvis was a racist” argument at the same time in “How Did Elvis Get Turned Into a Racist?”, his reasoned, fact-checked op-ed in the New York Times of August 11, 2007.

Newspaper headline: 'Elvis performance Disgraceful, Lewd and Disgusting'

Cut to November 2010. Your faithful friend and narrator is on sabbatical to Memphis, first stop Graceland. It had been three, maybe four years since my last visit to the Bluff City, but there was a time when I was there almost every weekend, for a period of nearly four years while I was writing a biography of Carl Perkins (Go, Cat, Go! The Life and Times of Carl Perkins, The King of Rockabilly, Hyperion, 1996); how many times I was there prior to starting the Perkins book, and how many times I’ve visited since completing the manuscript in 1994, I can’t say—too many to count. Like many Elvis fans, I was concerned when in December 2004 Lisa Marie Presley, Elvis’s daughter, sold most of the trademark and publishing rights to her father’s property to billionaire Robert F .X. Sillerman and his CKx, Inc. media and entertainment company (the parent, by the way of American Idol producer 19 Entertainment—do you get the sense this piece is heading into a dark area?), which acquired a majority interest in the assets comprising the Presley estate a year after Sillerman's Temenos project—a luxury hotel, condo and golf resort in Anguilla, British West Indies—went belly up, costing Sillerman the $180 million he had personally invested in it. (To his credit, Sillerman said resort development “was not my area of expertise by any stretch of the imagination.”) Sillerman had ambitious plans to upgrade Graceland that at one point included altering the actual property on which Elvis’s home sits—no more abhorrent an idea could Elvis fans imagine. Although Graceland is not a museum, it offers—or offered—various museum-like experiences in its car exhibit (which also served as a bit of a tribute to Elvis’s movie career, in that it included a drive-in like setup in which visitors could sit and watch clips of Elvis’s automobile-centric celluloid exploits) and in a free theater, The Bijou, that showed an amazing 20-minute biographical film titled Walk A Mile In My Shoes, complete with Elvis’s own commentary, movie and concert footage and altogether amazing performances from the legendary 1956 Tupelo State Fair performance up to and including his 1968 comeback special, the sum of which pretty much explained Elvis’s enduring appeal. But museums evolve or die, and it seemed as if some of Sillerman’s bold pronouncements were worth exploring as a means of sustaining Graceland as a tourist Mecca, and providing a lasting tribute to Elvis’s artistry. On the other hand, he evinced no clear understanding of Elvis or of Elvis’s fans and seemed pretty much focused on making another fortune ahead of bolting the joint for other opportunities. So it was with great relief—make that “joy”—when news came this past May of Sillerman resigning as chairman and CEO of CKx, despite the Memphis Commercial Appeal reporting Sillerman would remain with CKx as a consultant.

I have no idea if what we see at Graceland today is the detritus of Sillerman’s planning, but an Elvis fan of long standing could not help but be dismayed by what I saw, or, as the case may be, did not see. These all boil down to one fact: Elvis fans come to Graceland because they are drawn by the music. Beyond the Elvis impersonators, beyond the women wearing Priscilla Presley beehives, the lure of the music has always been central to the Graceland visitors’ Elvis fixation. Yet, directly across the street from the Graceland mansion, in the Graceland shops proper, music is an endangered species. Only a couple of stores—notably the one attached to the entrance to the Elvis airplane tour, where the selection is wide and deep—carry any CDs or DVDs. The Bijou Theater is closed, and the Walk a Mile In My Shoes film gone. In the main lobby of the visitors center, various LCD TVs show Elvis performance clips, but these are free of any surrounding historical context or narration and are practically inaudible at the height of the business day, when the tourist traffic is at its peak and most voluble. You are not encouraged to sit and absorb what Elvis wrought as an artist—in fact, there are no seats.

Elvis introduces his version of Carl Perkins’s ‘Blue Suede Shoes’ to a national TV audience on the March 17, 1956 Dorsey Brothers Stage Show in New York.Down the block, beyond the Elvis airplanes, sits a small strip center comprised of four retail stores and a restaurant. Once was a time when all of these shops offered Elvis music and movies—everything the King had recorded and/or starred in, pretty much. These were the go-to resources for Elvis music and movies. Now, only one has any Elvis music to speak of; but in all of them you can buy Elvis tchotchkes of mind boggling variety: Christmas ornaments of dizzying permutations; potholders; shot glasses; playing cards; pricey costumes (yes, you can buy an Elvis-style Vegas jumpsuit) and other apparel; magnets. One shop was selling King-Size Magic Markers as Elvis memorabilia. (“That’s sad,” my son said.)

I came away from this trip feeling as if Graceland were consciously trying to diminish the achievements of Elvis the artist in favor of Elvis the cultural icon. Maybe that’s the future: as more generations come of age having missed any opportunity of experiencing Elvis’s music when it was new, or Elvis alive, the artist who created so formidable a body of work disappears, becoming something like a cartoon character—a fate that has not befallen the Beatles, who were in fact cartoon characters on Saturday morning TV for a moment but whose music, rightly, continues to inspire, influence and amaze succeeding generations. There are obvious reasons for the evolving cultural personas of Elvis and the Beatles, but we’re not here to consider those right now.

The assault on Elvis the artist reaches beyond the confines of Graceland, though, into the pages of the New York Times, where, in a November 16, 2010, Holiday Gift Guide roundup of “Music Boxed Sets” the following appraisal of The Complete Elvis Presley Masters appeared: www.nytimes.com. Snarky, uninformed and insulting, this capsule review gives the reader no indication whatsoever of the boxed set’s contents, concept or packaging, but at least the staggering price ($749) is noted.

Elvis, ‘Follow That Dream,’ from the like-titled 1962 movie.In fact, The Complete Elvis Presley Masters is a resounding statement, a groundbreaking artist’s definitive commercial work—711 master recordings, everything released during Elvis’s lifetime. The 103 rarities (comprising three discs)—alternate takes, outtakes, rehearsal jams, home recordings, live and radio performances—are practically afterthoughts in contrast to the polished final versions. It begins in 1954, in the Sun Studio, where 19-year-old Elvis records the pop tune “Harbor Lights,” originally released by Frances Langford in 1937 but a hit in 1950 for five different artists, the most popular version being by the Sammy Kaye Orchestra, which topped and stayed on the charts for 25 weeks; it was also a hit for Bing Crosby that year, which is the most likely source for Elvis’s version. “Harbor Lights” was but one song out of four recorded during an epic session that also yielded “I Love You Because” and, critically, Elvis’s first single, a furious reading of the Arthur Crudup blues, “That’s All Right” and the B side, a similarly propulsive 4/4 interpretation of Bill Monroe’s “Blue Moon of Kentucky” that had Sam Phillips exclaiming, “Fine, man. Hell, that’s different. That’s a pop song now, nearly ‘bout.” These four numbers, from a July 5-6, 1954 date at Sun, begin Elvis’s commercial career; on disc 29 the journey concludes with “Unchained Melody,” the now famous tortured live version from Elvis’s June 21, 1977 show at the Rushmore Civic Center in Rapid City, South Dakota. (Disc 30, the final disc, is an interesting collection of outtakes, home recordings, studio rehearsals—including one for “Viva Las Vegas” in 1963—and obscurities such as the rehearsal jam on “Ghost Riders In the Sky” from the FTD album The Way It Was.) Name an Elvis hit, and it’s here, and in beautifully restored audio that revitalizes the presence and intimacy of recordings we’ve been hearing for decades.

The listening experience of this boxed set can be somewhat duplicated in a number of less pricey boxed sets and to a lesser extent in single- or multiple-disc retrospectives—not as comprehensively, of course, but several collections do survey the entirety of Elvis’s recorded legacy. Try the Elvis 75: Good Rockin’ Tonight four-CD box released a year ago this month, the centerpiece of an Elvis cover story in this publication, or the meat-and-potatoes double-CD from 2007, The Essential Elvis Presley. Of course, what you miss, for the most part, with any other collection, is a meaningful immersion in the variety of styles Elvis owned—gospel, pop, country, rock ‘n’ roll, blues, Christmas songs, love songs. Try the truncated single-disc version of the Elvis75 box. During my abovementioned Memphis pilgrimage, I drove around Memphis listening to this disc, moved anew by the conviction and authority of the King’s performances, trying in vain to think of a single artist working today who could range from “That’s All Right” to “How Great Thou Art” to “In the Ghetto” to “Suspicious Minds” to “Can’t Help Falling in Love” and still be believable, still evince an understanding of the shadows as well as the light of the songs’ emotional components, sing each tune as if something were at stake. Okay, one—a healthy and focused Aretha, with the right producer.

What else do you not learn from the New York Times review? How about that the set includes an impressive 240-page hardbound book? Its contents include not only a painstakingly researched discography by Ernst Jorgensen, the foremost Elvis archivist/historian (and director of RCA’s Elvis catalogue for more than twenty years, and co-author with Peter Guralnick of the essential Elvis Presley: A Life In Music, the authoritative guide to all of the artist’s recording sessions), but also a new 6,000-word essay by Guralnick. You might think, after two weighty volumes of Elvis biography, Guralnick would have run out of things to say about the artist, but he rises to the challenge here with still more insightful observations about Presley’s music and style, acknowledging fully the physical and emotional problems that undercut many of Elvis’s sessions in the last five years of his life that resulted in “a steep falling-off” in the music’s quality. But, unlike the critics all too eager to write off latter-day Elvis, Guralnick has listened and noted the truth of the matter, to wit: “There are poignant moments at the end, made all the more poignant by the spectacle of someone struggling so mightily to find his voice.”

‘Viva Las Vegas’: Elvis scorches the great Doc Pomus-Mort Shuman tune in a terrific scene from the movieGuralnick’s final word: “For twenty years he bestrode the pop world in a manner unlike anyone else—and not, it should be noted, with a style that was either static or imposed upon him. Rather, he was an artist who continued to evolve, someone constantly reaching for something not quite within his grasp. Whether as the brashly shy teenager who could boast that he didn’t 'sound like nobody,' as the pop idol who sought to redefine his work, or as the Las Vegas performer determined to incorporate every strand of the American musical experience, his mission remained the same: to carry his message out into the world. It was a message based upon the belief that there was something spiritual about the music, that music could transcend the day-to-day burdens that we all bear, that it could reach across boundaries of color and class, create a sense of empathy for the other person, and erase categories—musical, political, and social—if only for the moment that it was being shared. Think of his work as indivisible then. Only in that way can one be true to the spirit of the music and the man.”

As usual, Guralnick nails it about Elvis’s music, hearing in it the inclusiveness, indeed, the humanity, at the heart of the artist’s worldview.

“The lack of prejudice on the part of Elvis Presley,” Sam Phillips told Guralnick, “had to be one of the biggest things that ever happened. It was almost subversive, sneaking around through the music, but we hit things a little bit, don’t you think?”

Elvis, ‘As Long As I Have You,’ from King Creole, 1958In the end, to those who insist on leveling baseless, repugnant charges against Elvis, we are reminded of what Massachusetts Representative Barney Frank said to a right-wing lunatic at one of his 2009 Town Hall meetings, who referred to the impending health care reform legislation as a “Nazi policy.” Said Rep. Frank: “It is a tribute to the First Amendment that this kind of vile, contemptible nonsense is so freely propagated."

More succinctly, as Little Richard would put it: Shut up!

The Complete Elvis Presley Masters, released on October 19, 2010, is available in a limited edition first run of 1,000 copies only at www.completeelvis.com.

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024