‘I’m A Romantic Guy’

Henry Mancini’s music for Blake Edwards’s films endures, and still touches the hearts of new generations of huckleberry friends. Herewith a look at what Mancini wrought in 'Peter Gunn,' 'Moon River,' 'The Days of Wine and Roses' and 'The Pink Panther Theme'—the songs that made him a legend.

By David McGee

It may seem that if Henry Mancini had not existed, Blake Edwards would have had to invent him. Or vice versa. Of Edwards’s 38 films, 28 are graced by Mancini’s music—music so evocative, so beautiful, at times so daring that the films and their scores are inseparable, impossible to imagine without each other. Their director-composer partnership is rivaled in film history only by that of Alfred Hitchcock and Bernard Herrmann, but the latter pairing, however memorable and, indeed, towering, lasted but nine films, from 1955’s The Trouble With Harry to 1966’s Torn Curtain (and in fact, Hitch was do dissatisfied with Herrmann’s score for the latter that he had it replaced in the final version. See the 50th Anniversary tribute to Psycho in the June 2010 issue of TheBluegrassSpecial.com for a complete critical overview of the Hitchcock-Herrmann oeuvre).

Herrmann, who was most proud of his achievements as a conductor, and regarded the film work as secondary to his classical pursuits, enhanced the symphonic elements of film music while working within a stylistic framework long indebted to the symphonies of Tchaikovsky (portions of whose ballet music for Swan Lake, by the way, was appropriated as the theme music for the original Frankenstein and Dracula movies). Born April 16, 1924 to a working class family in Cleveland, OH, Mancini studied Puccini and Rossini in his childhood years, studied with a theater conductor and began arranging music in his teens, attended Juilliard but dropped out to serve in the military in WWII, and returned from the war to become pianist and arranger for the Glenn Miller-Tex Beneke orchestra.

Mancini’s first Hollywood assignment came in 1952, for Abbott and Costello’s Lost in Alaska. For the next six years he was under contract to Universal, where he arranged or scored (in full or in part) more than 100 films (Creature From the Black Lagoon, This Island Earth, It Came From Outer Space, et al.), including a celebrated, and Academy Award-nominated, score for 1954’s The Glenn Miller Story that reflected Mancini’s growing interest in jazz. But the score that put him on the big-time Hollywood map was for Orson Welles’s 1958 noir classic, Touch of Evil. In addition to his dramatic background music, Mancini was among the first composers to employ as part of his score source music—music emanating from a visible source in the story, such as a radio, or in a nightclub (the radio in one of the motel scenes in Touch of Evil becomes as much a malevolent presence as the thugs terrorizing Janet Leigh).

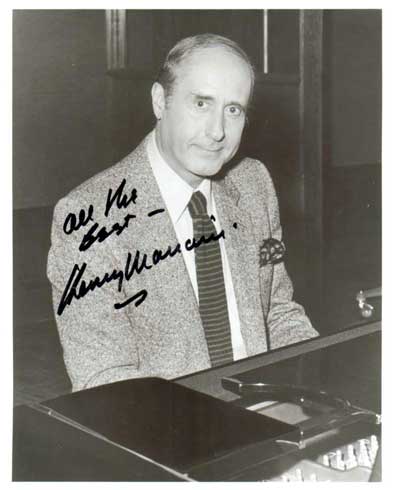

Mancini conducting: ‘The cool, small group jazz sound he created for Peter Gunn started a one-man revolution in the way television music could sound and ought to sound…his music for the movies, from Breakfast at Tiffany’s forward, has been its own revolution, ending the tyranny of Tchaikovsky imitations and Rachmaninoff as sounds of the cinema. He introduced wit, modern romanticism and…a spare, haunting chamber quality to film music…’

In 1957, however, Mancini had crossed paths with young director Blake Edwards—and it really was not much more than a crossing of paths when penny pinching Universal executives needed Mancini’s help in retrofitting music from other Universal films for use in the Edwards-directed Tony Curtis vehicle, Mister Cory. As Mancini explained it in his autobiography (Did They Mention the Music? The Autobiography of Henry Mancini, with Gene Lees, Cooper Square Press, 1989): “I didn’t write the score for that picture, but as often happened when they needed music in a pop vein, I had been brought in for some source cues.” Shortly after finishing work on Mister Cory, Mancini was out of a job, as Universal laid off most of its music staff, him included.

Television turned out to be the medium in which the Edwards-Mancini collaboration first flowered, when the director asked Mancini to score his new series, Peter Gunn, in 1958. Joe Manning, at his website Mornings on Maple Street describes what happened next:

On a late summer evening in 1958, at Radio Recorders, a legendary recording studio in Santa Monica, California, a mild-mannered 34-year old conductor, pipe in mouth, gives the downbeat, and a guitarist, also 34 years old, starts grinding out a heavy, rolling ostinato. Two bars later, a curly-haired 26-year-old pianist makes his entrance, banging out the same line in unison. Suddenly, a raucous horn section jumps in, soon joined by a boisterous alto sax. In two minutes, it ends with one final gasp of energy. The groundbreaking Peter Gunn theme is in the can.

The conductor was, of course, Henry Mancini, soon to become the most innovative and influential film composer of the last 50 years. The guitarist was Bob Bain, a stalwart who cut his teeth in the Tommy Dorsey and Bob Crosby bands after the war. The alto player was Ted Nash, on his way to becoming one of Hollywood's leading studio musicians. The pianist? It's now a great trivia question. It was Johnny T. (Curly) Williams, who later shed his curls and made his mark as the one and only John Williams, forever linked with the films of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg. Looking back at the TV show and the RCA album sessions, just about everyone connected with them built great careers on the strength of four minutes of music.

The premise of the show called for Gunn (Craig Stevens), a private detective, to spend much of his time at Mother's, a nightclub where his girlfriend, Edie Hart (Lola Albright), sings with a jazz combo. So the use of jazz as source music was a natural choice; but when Mancini elected to score the action and dramatic scenes with jazz as well, he wound up giving the show its most identifiable and marketable quality.

In a recent interview, Ginny Mancini, Henry's widow (he passed away in 1994), told me that her husband was "inspired by the cool romantic side of the relationship between Peter and Edie. He thought the music needed to be strong, sexy, and get your attention. He would sit down with Blake and spot where the music should come in and where it should go out and what it had to say. He pretty much had it in his head before he sat down at the piano."

The prominent jazz critic Leonard Feather always took Mancini seriously as a jazz-influenced composer, and indeed penned insightful liner notes for two now-out-of-print vinyl collections of Mancini’s music, the double album This Is Henry Mancini (1970, RCA) and the single LP, A Legendary Performer (1976, RCA). In his comments to Feather as documented in This Is Henry Mancini, the composer points out in response to a question about studios hewing to “conservative European-music concepts,” that “the studio had big staff orchestras and, most likely, when you wrote a score, you thought in terms of the maximum you had to work with, mostly the concept was lushness and bigness. By the very nature of it, ‘Peter Gunn’ caught the ear because of the sparseness of it, the economy of sound. I guess they were, so to speak, underwhelmed.”

Edwards had told Mancini, says the composer, “I don’t want any music in this except what you feel—what we feel together—and it should be now.”

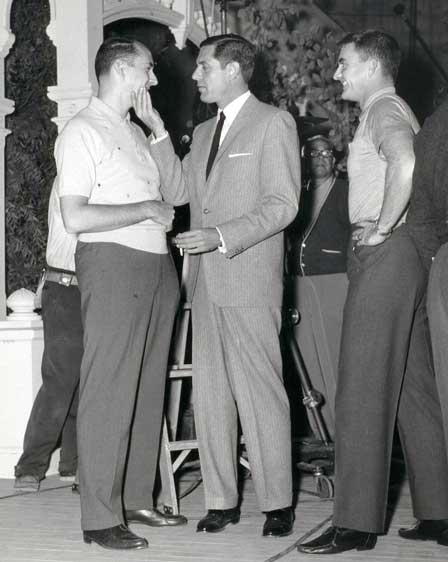

Henry Mancini, Peter Gunn star Craig Stevens, director Blake Edwards. Photo courtesy the Mancini Estate.

Mancini saw himself as part of a new breed of arrangers and composers. More conversant with jazz and pop than was the old guard, these artists were pioneering a new approach to TV and film music, and the studios were pushing back against. “I think it was avoided not because of its jazz orientation,” Mancini told Feather, “but because a new breed of writer had not yet come of age, a breed that was represented during the 1960s by men like Neal Hefti, Quincy Jones, Lalo Schifrin, among others. All of us were different because of our dance-band or jazz associations. Hardly any of the studio arrangers at that time had had that kind of experience. Even the few exceptions to that rule were rarely given anything to do aside from big musical numbers at MGM or Fox. It was thought that men with our sort of backgrounds didn’t have the ability to score a film or a TV series. Well, luckily, I came in through the door by paying my dues during those six years at Universal.”

Peter Gunn was an exciting TV series, and its success put Blake Edwards on the map as a director, but Mancini’s achievement with the music—which earned him two Grammy Awards in 1958—the first year the Awards were presented—for Album of the Year and Best Arrangement—was groundbreaking. The eminent L.A. Times film critic Charles Champlin proclaimed: “The cool, small group jazz sound he created for Peter Gunn started a one-man revolution in the way television music could sound and ought to sound…his music for the movies, from Breakfast at Tiffany’s forward, has been its own revolution, ending the tyranny of Tchaikovsky imitations and Rachmaninoff as sounds of the cinema. He introduced wit, modern romanticism and…a spare, haunting chamber quality to film music…he is a tastemaker in the most useful sense.”

Not a bad outcome, given how the Edwards-Mancini association began with a chance meeting as Mancini was exiting the Universal Studios barber shop. Speaking to Valerie Sagers in 1982, Mancini explained: “Blake was on the lot doing something and when you come out of the barber shop, you go into the commissary. I was coming out of the barber shop and he was going in for lunch. So it was just a chance meeting. And he asked me about doing Peter Gunn. We had been socially friends for a long time, but that was just a chance [that day] and he had probably been thinking—Blake is impulsive that way—and of course, I had my mojo out. I needed a job at the time and maybe I looked hungry and he took pity on me. If it had been the next day, he may have run into Nelson Riddle, I don't know!”

Henry Mancini, ‘Peter Gunn’: in contrast to the big orchestral arrangements for TV theme music that studios were used to, the theme for Peter Gunn ‘caught the ear because of the sparseness of it, the economy of sound,’ said Mancini.However groundbreaking the music for Peter Gunn, Mancini’s score for Edwards’s 1961 film, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, did more for his legacy, and for the fate of the film, than any other work he did with the director. The score is delightful in a swingin’ ‘60s kind of way—happy, carefree, buoyant, spirited—but it was one song, “Moon River,” that jumped out to become a certified classic—one of those songs you can safely say is likely being played somewhere in the world at just about any moment of the day. Mancini claimed he wrote the melody in half an hour; commissioned to write the lyrics was Johnny Mercer, one of the great classic pop songwriters in American history then at a low ebb in his career in the wake of rock ‘n’ roll’s rise pushing his type of song off the air and off the charts. Called into service, he came up big. Mercer conjured precisely enough of the film’s main narrative arc—“two drifters off to see the world/there’s such a lot of world to see”—and fleshed out his storyline with winsome, poetic, ethereal evocations of those two drifters’ aspirations. There was no river to speak of in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, unless you count the view of the Hudson we get when Holly Golightly travels to Sing Sing to visit her benefactor Sally Tomato, but a river runs through Mercer’s youth in Savannah, Georgia, the Back River (now rechristened Moon River in the songwriter’s honor), and just as he and his huckleberry picking friends used to sit on its banks and see bigger worlds beyond their river, so do kept-man/struggling writer Paul Varjak (played by George Peppard) and country girl-turned-fashionable big city escort Holly Golightly (Audrey Hepburn) float down a river of their own imagining, until they land at rainbow’s end together at the film’s close. The song is so beautiful and so heart tugging it causes even hard-boiled critics to soft-pedal the unsavory nature of Truman Capote’s main characters and even to give Edwards little more than a slap on the wrist for Mickey Rooney’s horrifying racist portrayal of Holly’s Japanese landlord/photographer Yunioshi.

Mancini and Mercer had been friends since Mancini’s early days in Hollywood, when his wife Ginny, who sang with Mel Torme’s Mel Tones group, worked with Mercer on the Armed Forces Radio Service programs. “He was every bit as much of a poet then as he was years later when we worked together,” Mancini told Leonard Feather. “For me he’s number one, and I know my other lyricist friends would defer to that judgment.”

Mancini may have written the “Moon River” melody in half an hour, but Mercer—a perfectionist on a par with Mancini—had a bit of a struggle with the lyrics. Originally he worked with the title “Blue River,” until he learned another songwriter was working on a similarly titled tune; his original opening lyric was directly inspired by the book’s/film’s main character: “I’m Holly, like I want to be/like Holly on a tree back home…” But when “Blue River” became “Moon River,” and Mercer began reflecting on his childhood back in Georgia, the river that ran through it and the “rainbow’s end” he and his friends—who did indeed pick huckleberries (blueberries) together—envisioned for themselves in years ahead, the lyricist’s approach became less character-specific and more the product of dreams and poetry, an intermingling of hope and romance, with a subtle undercurrent of sadness that had the odd effect of enhancing the sunrise effect—the auguring of a new day—in the song’s hopeful closing sentiment, “my huckleberry friend, Moon River and me.”

“We had a band rehearsal at a hotel in Beverly Hills,” Mancini related to Feather. “I asked John to meet me there. He arrived early; there was nobody else in the room. It was an eerie feeling in that big, deserted ballroom with empty tables, and chairs piled up. I sat at the piano and John sang several sets of lyrics. The first was called ‘I’m Holly,’ which of course was Audrey Hepburn’s name in the picture; and we decided that was a bit too literal. There was another one that somehow worked in the actual words ‘Breakfast at Tiffany’s.’ But the one called ‘Blue River,’ later changed by Johnny to ‘Moon River,’ seemed just right, so we decided that was the one to use; and with the exception of John’s wife Ginger I guess I was the first person who ever heard that memorable phrase ‘my huckleberry friend.’ I still get a chill out of it, because it said so much in so few words.”

Henry Mancini (left) and Johnny Mercer, holding their Oscars for ‘Moon River,’ flank presenter Debbie Reynolds at the 1962 Academy Awards ceremony.Leonard Feather: “‘Moon River,’ a melody and poem of elegiac poignancy, succeeded beyond its creators’ wildest predictions. At last count there were over 700 recorded versions worldwide. [Ed. note: This was written in 1976.] Significantly, the melody is based on a structure (A-B-A-C) that is very simple, on a harmonic pattern that is beautiful in its logic, and on a melody that dovetails exquisitely with the harmony.”

Yet, one of Tiffany’s producers hated “Moon River” and ordered Blake Edwards to “get that damn song out of it.” Audrey Hepburn not only countered with “Over my dead body!” but insisted on singing it herself rather than using the voice double the studio was insisting on. In a rare vocal performance, Hepburn, looking stunning in a blue jeans, a sweatshirt and a white towel covering her hair, sits in her window strumming an undersized acoustic guitar, and makes the song her own in a captivating, beautiful cinematic moment.

“Moon River” was the Academy Award for Best Original Song in 1961 and a year later a Grammy Award for Record of the Year. His score for Breakfast at Tiffany’s won Mancini an Oscar for Best Original Score.

‘Moon River’ montage from Breakfast at Tiffany’s: ‘…the product of dreams and poetry, an intermingling of hope and romance, with a subtle undercurrent of sadness that had the odd effect of enhancing the sunrise effect—the auguring of a new day—in the song’s hopeful closing sentiment, ‘my huckleberry friend, Moon River and me.’For his next project with Edwards, Mancini again called on Mercer and the two came up with another Academy Award winning song in the title track for The Days of Wine and Roses—a poignant, romantic song to accompany Edwards’s brutal examination of a husband (Jack Lemmon) and wife (Lee Remick) descending into the depths of alcoholism. The 1962 movie’s title came from a poem, “Vitae Summa Brevis” by the English writer Ernest Dowson:

They are not long, the days of wine and roses/Out of a misty dream/Our path emerges for a while, then closes/Within a dream.

The Mercer lyrics are equally succinct:

The days of wine and roses laugh and run away like a child at play

Through a meadow land toward a closing door

A door marked "nevermore" that wasn't there beforeThe lonely night discloses just a passing breeze filled with memories

Of the golden smile that introduced me to

The days of wine and roses and you“The title seemed to dictate the first phrase of the melody,” Mancini said, “and that was the first thought I had in mind when I sat at the piano. It just sort of wrote itself from there. In fact, ‘Moon River,’ ‘The Days of Wine and Roses’ and ‘Charade’ were very fast in realization once I conceived the basic idea and knew what I was going for.”

Andy Williams’s 1963 version of Mancini-Mercer’s ‘The Days of Wine and Roses.’ Said Jack Lemmon: ‘When Johnny was through playing it I just sat down and cried. I thought this was the most beautifully appropriate song ever written for a film.’In 1963, for Edwards’s now-classic first installment of the Pink Panther series starring Peter Sellers, Mancini sought no lyrical help from Mercer or anyone else, but instead crafted a slinky, infectious, jazzy, sax-powered tune (sax by New Orleans legend Plas Johnson) that was a perfect fit both for the film and the hip Pink Panther cartoon character introduced and turned into a star in the opening credits. “The Pink Panther Theme” is the most-performed Mancini tune of all, even outstripping “Moon River.” The highest compliment of all came from the film’s male star, Jack Lemmon, who recalled that filming was almost complete when Mercer came to the set with the finished song. “When Johnny was through playing it,” Lemmon said, “I just sat down and cried. I thought this was the most beautifully appropriate song ever written for a film.”

“This is one instance where I heard the sound in my mind before I heard the actual melody,” Mancini explained. “I wanted that breathy, low-register tenor sax sound, a cross between Lester Young and Ben Webster; and Plas Johnson had exactly that quality to contribute, along with a kind of saucy attitude and a nice attack.

“When I wrote this for the movie in 1963, I thought of it in the same way that writers used to contribute specialties for individuals within a big band. In fact, this had big band written all over it. I still play the original version in concerts, and from the first notes of the opening vamp—sometimes even before that, during the opening bell-tone effect—the applause invariably starts. It’s nice to have that kind of reaction to an instrumental piece.”

Henry Mancini’s theme song for The Pink Panther, 1963: ‘I wanted that breathy, low-register tenor sax sound, a cross between Lester Young and Ben Webster; and Plas Johnson had exactly that quality to contribute, along with a kind of saucy attitude and a nice attack,’ said Mancini.No enduring hits—or even a memorable melody, for that matter—emerged from the next Edwards-Mancini project, but the two pushed their collaborative envelope in intriguing fashion in 1962 in hearkening back to the director’s Peter Gunn era with a taut, chilling film noir exercise, Experiment in Terror, filmed on location and in black and white in San Francisco. (The tense finale is played out at the old Candlestick Park and includes both actual game footage of the SF Giants against the Los Angeles Dodgers—Giants outfielder Harvey Kuenn is shown doubling—and a memorable staged shot of the Dodgers’ fireballing righthander Don Drysdale winding up and pitching into the camera in a POV shot.) Lee Remick returns to the Edwards troupe here as Kelly Sherwood, a bank teller who is attacked in her garage by a shadowy thug with an asthmatic voice (Red Lynch, played with pitch perfect malevolence by Ross Martin), who demands she help him steal $100,000 from the bank. That she capitulates in this scheme is out of fear the “phantom asthmatic,” as he’s referred to in the script, will carry out his threat to kill her and her 16-year-old sister Toby (Stefanie Powers)—and he makes sure Ms. Sherwood knows that he knows every movement she, Toby and Toby’s friends make. In a panic she calls FBI agent John Ripley (Glenn Ford), who becomes convinced of the plot’s seriousness and with stealth and caution sets out to track down Lynch before tragedy ensues. There is no sweet romance here—the chemistry between Remick and Ford betrays no underlying sexual tension, only the intensity fueled by her fear and his unwavering focus on carefully putting the pieces together in time; and no bumbling detectives—Ford’s Ripley, and the other police and FBI agents as well, are pros who meticulously gather evidence, interpret clues and watchfully wait (while providing avuncular counsel to calm Remick’s frazzled Sherwood) in order to see patterns and predict behavior. For atmosphere, Mancini composed a sinister sounding score, full of dissonant tones and brooding jazz themes played largely by tenor saxes and/or a stark, unaccompanied piano plunking out dark phrases. In mood, pacing, composition, economy (of writing, acting and music) and a spectacular ending on the pitcher’s mound at Candlestick, Experiment in Terror ranks as one of the unacknowledged noir classics and one of Mancini’s most scintillating scores, again using original and source music to great advantage (in particular, a radio playing at a swimming pool scene featuring Toby and one of her young male suitors is tuned to some ferocious instrumental rock ‘n’ roll as purveyed by a brittle, distorted guitar of the sort you would not hear on the Top 40 at that time).

The trailer for Blake Edwards’s Experiment in Terror (1962)Twenty-four more Edwards/Mancini collaborations ensued. At his death from pancreatic cancer on June 14, 1994, Mancini was working on a Broadway stage version of Victor/Victoria, the 1983 movie version of which earned him (working with lyricist Leslie Bricusse) his fourth Oscar, for Best Music, Original Song Score and Its Adaptation or Best Adaptation Score.

In his abovementioned interview with Valerie Sagers in 1982, Mancini was asked why so much of his music had a romantic tinge. Mancini didn’t have to think hard to come up with an answer: it was in the blood.

“If you look at it, first of all, I'm a romantic guy,” he told Sagers. “Being Italian from both sides of the fence, melody has always been very important to me. And therefore, melody inevitably leads to romance—you can write that on your list there! (laughs) I'm a melodic writer and therefore a lot of the kinds of pictures I've done have taken that approach. So therefore, you get the love songs like ‘Days of Wine and Roses,’ ‘Moon River,’ ‘Two for the Road,’ ‘Dear Heart’ and all those things. And those are actually results of what's up on the screen. It has nothing to do with what I wanted it to do; in other words, I see the picture and then I come up with what I thought is the proper cases I just mentioned and with several others, it's been romantic music.”

After all the awards, after all the honors, as the films he worked on with Blake Edwards and other directors endure, Henry Mancini’s music still speaks most eloquently for him. Once heard, it’s always with us, and sometimes it beckons us like no other sound can. Critic Marc Meyers experienced this phenomenon and documented it in his JazzWax blog of September 4, 2008. Mancini fans can relate:

I'm not sure why, but I had a strong craving for Henry Mancini yesterday. Mancini's music is cinematic and commercial in approach but always much more sophisticated than you imagine on a careful listen. There's a hip, fizzy sensibility to nearly everything Mancini wrote, and his best works mash together the sonic personalities of instruments to produce supersized tones and textures. What's more, a good part of his work conjures up images of the swinging 1960s—bright colors, cars with curves, suit jackets with just a fine hint of white kerchief, molded plastic, perfectly mixed drinks and extended eyelashes.

It’s all waitin’ ‘round the bend…

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024