The Human Condition, Well Served

By David McGee

SINATRA/JOBIM

Francis Albert Sinatra & Antonio Carlos Jobim

The Complete Reprise Recordings

Concord RecordsNever has a Frank Sinatra album made it to market with more behind-the-scenes drama than 1967’s Frank Sinatra & Antonio Carlos Jobim. The sessions went smoothly enough, with a group of accomplished players hailing from Jobim’s native Brazil blending well with Sinatra’s favored Hollywood session men (including his pianist Bill Miller, of whom Sinatra joked, when asked if he thought a piano part in one song was a bit too forceful: “Him percussive? He’s got fingers made out of jello.”), under the production eye of another Sinatra favorite, Sonny Burke, with Jobim’s producer, Portugese speaking Ray Gilbert, at his side. To this multicultural cast add one of Sinatra’s favorite arrangers, German-born Claus Ogerman (“Yes the introduction. I will slow down each time the fourth beat.”), who did nothing less than fashion a batch of elegant, mellow arrangements comparable to the classic work Nelson Riddle did with the Chairman of the Board. The ensuing album arrived on the Billboard chart and stayed for 28 weeks, peaking at #19 in April ’67. Two years later, virtually the same cast of characters assembled for another round, the one key difference being the supplanting of Ogerman as arranger with Eumir Deodato. Younger and more attuned to the day’s pop music tends than Ogerman, Deodato brought a bit of sizzle to his charts, but only so much as to heighten the heat of the romantic tunes, not to turn it into some kind of fusion experiment.

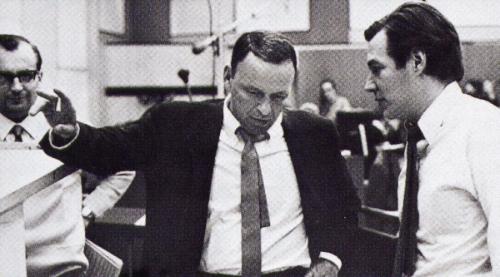

Frank Sinatra and Antonio Carlos Jobim in the studio during sessions for the Francis Albert Sinatra & Antonio Carlos Jobim album. Sessions took place at Western Recorders, Studio One, in Hollywood, Jan. 30-Feb. 1, 1967. Arranger Claus Ogerman is at left.Just when the execs at Reprise were thinking everything was fine and dandy. Upon hearing the 10 completed songs played back in the studio, Sinatra, despite having a bit of trouble getting a handle on some of the Jobim/Deodato approaches, had announced, “Gentlemen, we have an album." A cover shot was taken of a casually dressed Sinatra standing casually, one leg crossed over the other, behind a Greyhound bus parked in a wooded area. The entire label business infrastructure was gearing up to promote the new release.

Then came a call to the office from Sinatra himself and a three-word message to the person on the Reprise end of the line: “Kill the album.” He doesn’t like the cover, and especially doesn’t like how he sounds on some of the songs—too strained, too detached, not in charge of the moment. All the arguments in defense of the album are rebuffed by Sinatra—he even (rightly) complains that the time constraints on the 8-track version (anyone remember 8-tracks?) force the editing of the song “Wave,” which ends side one, into two parts where the tape runs out, with the second part beginning when the tape reverses.

Jobim, though, likes what he hears. He suggests he release it himself, if Reprise won’t. Debate ensues between the Sinatra and Jobim camps, and finally the Chairman concedes that seven of the 10 tracks are worthwhile endeavors. Jobim is holding out for all 10. The compromise is to release the Sinatra Seven (or, to be entirely accurate, the Jobim Seven, since all are Jobim compositions) with some other straight-ahead classic pop recorded with arranger Don Costa, who would figure prominently in the artist’s latter-era recording history. So the Sinatra/Jobim Seven and seven other Costa-arranged sessions (including John Denver’s “Leaving On a Jet Plane” and “My Sweet Lady,” Joe Raposo’s Kermit the Frog anthem, “Bein’ Green,” Bacharach-David’s Carpenters smash, “Close to You,” among others) become a 14-song album, Sinatra & Company. Released in 1971, it was less successful than the previous Sinatra-Jobim summit, peaking at #73, but maintaining a 15-week chart run.

Neither one of the two Sinatra/Jobim albums is easily available in their original incarnations. (As of this writing, the 1969 album, remastered for CD, is priced at almost $70 new, the vinyl version at $199 new, and import versions for $17.98 or $120; Sinatra & Company is available via Amazon as a pricey import, or as a cheap audio cassette and $40 vinyl version). But now, in 2010, all of their recordings together—including the three excised from consideration for Sinatra & Company—are compiled on the single disc under consideration here. As for the principal artists, former Warners exec Stan Cornyn (who was present at the sessions for both albums) reminds us in his liner reminiscence that the international airport in Jobim’s native Rio de Janeiro is named after the great Brazilian composer (who died in 1994) and Sinatra’s face is now on a U.S. postage stamp.

So what do we have? Not to beat around the bush, but these songs boast an insidious quality—on first listen you might think Sinatra was right in his reluctance to have some of the tracks released for public consumption. He’s not into it, you might think; he’s somewhere else, unfocused and enervated, struggling to find the heart of this tune or that. But listen again—and really, the second time through should do the trick—and you will hear the Chairman in a performance of sustained cool and fierce but consciously restrained passion unlike any other album-length performance in his career. He’s not as Homerically melancholy as on the monumental classics of Wee Small Hours (1955), Frank Sinatra Sings for Only the Lonely (1958) or September of My Years (1965), but the songs don’t require him to be, either. These are mostly Jobim compositions (only three are not: a smoldering take on Irving Berlin’s “Change Partners”; a similarly sensuous, Latin-infused rendition of Cole Porter’s “I Concentrate On You”; and a suggestively frolicking reading of “Baubles, Bangles and Beads,” a song from the Broadway musical Kismet that had been a hit for Peggy Lee in 1954, the same year Sinatra first recorded it), and let it be said the principals didn’t mess around—they went for the tape-measure blasts in Jobim’s portfolio, starting off the album with a prodigious shot in the form of “The Girl from Ipanema,” the song that put Jobim on the map in the U.S. in 1963, when his collaboration with João Gilberto (and Gilberto’s wife, Astrud, whose breathy, coquettish reading of the lyrics ranks with the ultimate moments in recorded vocal seduction) set off a bossa nova craze in these parts. Just as Astrud sang from a specifically female point of view, with no small hint of irony and relish in describing the unattainable Girl’s allure and distracting effect on the male populace, so does Sinatra become the man inexorably drawn to the Girl, all the while recognizing the futility of his pursuit. Jobim replicates his vocal on the original, and his acoustic guitar punctuations evoke wonderful memories of the 1963 classic, but Sinatra takes it somewhere else as he expresses the growing frustration of being ignored. You can hear that frustration simmering when he breaks up the rhythm into a staccato “Tall. Tan. Young. Lovely.” litany as the song winds down, and lifts his voice hopefully on the word “smile” in “when she passes I smile…” before returning to a somber, “…but she doesn’t see”—then repeats variations on the phrase as Jobim shadows him, singing in Portuguese, until Sinatra gets to the heart of the matter, improvising, “She doesn’t see me,” to put the final hurt on the lament. True to his style, Sinatra is approaching this timeless tune, definitively done in its original version, with the intent of putting his stamp on it by making it personal, not by trying to conjure the spirit of Astrud, or competing with her, or attempting to one-up her. It’s a measure of the respect he has for her interpretation that he takes his to a place no one else had ventured, and makes it work—so much so that if there is a choice between cueing up the Getz/Gilberto version or the Sinatra/Jobim version, it would be a difficult call, as both stand apart as simply great performances, perfect in all dimensions.

The original version of ‘The Girl From Ipanema,’ Astrud Gilberto with Stan Getz on sax“The Girl from Ipanema” sets the pattern for what’s to come, with pillars of the Jobim songbook taking on fresh characteristics arising equally from the Ogerman/Deodato arrangements, Sinatra’s breathtaking command of understatement, and Jobim’s ethereal presence vocally and on guitar. The elements coalesce beautifully on countless numbers, not least of these being the soothing, autumnal “Dindi” (another Jobim tune given a near-mystical treatment by Astrud Gilberto), with its subdued Jobim guitar strumming and Riddle-like string flourishes, now soaring and keening, now humming and tender. The same could be said for another Getz/Gilberto (João and Astrud) tour de force that has entered into the common language of international music, “Quiet Nights of Quiet Stars (Corcovado).” Calming woodwinds replace the original recording’s robust, Stan Getz sax interjections and set the stage for Sinatra’s pastoral yearnings and expression of rebirth, metaphysically and more, in a moment of romantic renaissance: “I who was lost and lonely/believing life was only a bitter, tragic joke/have found with you/the meaning of existence, my love…,” and the strings and woodwinds dance around each other as if evoking this bright new day of the soul.

Working with Deodato two years after the Ogerman-arranged sessions, Sinatra sings more forcefully, but then the Deodato arrangements are heavier on brass than Ogerman’s; in fact, on the oft-recorded “Agua de Beber” (“Drinking Water”—oft-recorded now, but at the time of these sessions only Jobim himself, Astrud Gilberto, Sergio Mendes and La Lupe with Tito Puente had cut the tune), the brass is so robust at times that you might think you’re in the midst of a Billy May arrangement. However, one of Jobim’s smash hits, “Desafinado” (it busted out of the Stan Getz/Charlie Byrd Jazz Samba album in 1964, but had previously appeared on Herb Alpert’s 1962 The Lonely Bull album and also in '62 on albums by Coleman Hawkins and Herbie Mann, and not least of all, on the groundbreaking Getz/Gilberto album that gave us the original “The Girl From Ipanema”), a duet between Sinatra and Jobim with wry, witty English lyrics by Jon Hendricks and Jesse Cavanaugh, is rampant with mock-serioso grievances directed at someone who insists the singer warbles off-key (hence the song’s subtitle, “Off Key,” as it’s billed here), but rides a crest of woodwinds, acoustic guitar, cooing strings and mellow percussion to a whimsical instrumental sign-off.

Frank Sinatra and Antonio Carlos Jobim, 1967, performing ‘Corcovado (Quiet Nights of Quiet Stars),’ Irving Berlin’s ‘Change Partners,’ Cole Porter’s ‘I Concentrate on You’ and ‘The Girl from Ipanema,’ from their album, Francis Albert Sinatra & Antonio Carlos Jobim. Pure and simple, great music, vital, timeless, essential, with two exceptional artists’ big hearts fully open and expressive. The human condition is well served in these hands.So it goes, an album both intoxicating and mesmerizing, a merging of superior artistry from many corners of the pop world and a perfect fit all around. The Sinatra reissue program Concord has embarked on with the Frank Sinatra estate has already given us some revitalized classics, but this is the first of the discs to demand a whole new perspective on a particular segment of the Chairman’s work, as these recordings have never before been collected in one place. On this first chance to appraise the Sinatra/Jobim collaboration in toto, a pronounced continuity of approach and style obtains, no matter the years ensuing between sessions. So much for that. The more important point? This is great music. Pure and simple, great music, vital, timeless, essential, with two exceptional artists’ big hearts fully open and expressive. The human condition is well served in these hands.

Sinatra/Jobim: The Complete Reprise Recordings is available at www.amazon.com

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024