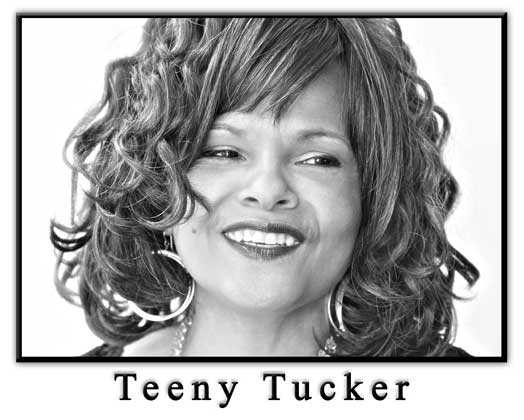

Teeny Tucker:Yes ma’m, whatever you say, ma’m. I’m with you all the way. (Teeny Tucker image from The Robert Hughes Center for Creative Imaging, www.roberthughes.net)Might Leave You In a State of Shock…

By David McGee

KEEP THE BLUES ALIVE

Teeny Tucker

TeBo RecordsIn his incisive liner notes for Teeny Tucker’s Keep the Blues Alive, producer-arranger-guitarist Robert Hughes relates how B.B. King told Ms. Tucker, “I want you to remember that you are not only a blues singer, you are a singer.” A formidable singer and blues singer himself, the now 85-year-old Riley B. King knows whereof he speaks, and Ms. Tucker proves the truth of his assertion with her every stirring note on Keep the Blues Alive. Yes, the form may be blues, or blues-based, but in the end Ms. Tucker vaults into the realm of pure, moving, human emotions, leaving in the dust all considerations of genre. This is good music, pure and simple.

‘You want to go with me? You better prepare to go first class!’ A sampling of the live fire Teeny Tucker brings on stage, at the 2003 International Blues Challenge, Columbus, OHEven so, Teeny Tucker wants you to know she’s all about the blues too—feels a sense of obligation to further the music and to honor the legacy of her late father, the beloved R&B singer Tommy Tucker of “Hi-Heel Sneakers” fame. That she achieves something larger than her animating impulses is testimony to the persuasiveness and personality of her artistry. Like a musical trial lawyer making her case, Ms. Tucker lays the proper foundation for her argument right off the bat: “Make Room for Teeny,” the second track, written for her by Pam and Lee Durley, is an infectious, bumping workout (featuring the lively, textured piano work of David Gastel) in which our gal makes it clear she's here to make a statement: “It’s time to turn the page/as Teeny takes the stage/I just might leave you in a state of shock,” she crows in a typical bit of good humored, self-referential testifying; no sooner is that done than does she ease into her autobiographical co-write with Hughes, “Daughter To the Blues,” a grinding, ominous treatise in which Ms. Tucker turns up the urgency in her voice in delineating the wisdom handed down by her late father, who both encouraged his daughter’s musical aspirations (“my daddy told me/when I was a little girl/you’re gonna be a singer/singin’ the blues/stop bein’ so shy, girl/when you sing your song/just sing the blues, girl/and you won’t go wrong…”) and offered seasoned wisdom about taking care of herself along the way (“one thing you told me/to pick and choose my fights/don’t be so shy, girl/just sing the blues/don’t listen to the naysayers/’cause they ain’t for you...”), all of which leads to a rousing ensemble crescendo and Ms. Tucker triumphantly declaring, “Blues will live forever!/And forever blues will be/he say you’re the daughter to the blues/and that’s the part of me I left with you,” out of which maelstrom Gastel emerges with a sustained, slow boiling harmonica howl, with Hughes following on his anguished heels with some stinging retorts on guitar.

As feisty as she is focused, Ms. Tucker subsequently struts through some interesting revelations of a more intimate nature. On the steady grooving “Old Man Magnet,” over Scott Keeler’s walking bass and Hughes’s stinging, six-string interjections, she makes her case for doing herself up right for a night of fun and romance (“when I show up for a party/I want to look real good/fix myself up like a woman should/’cause I’m an old magnet and they stick to me like glue”); by contrast, the chugging burner “I Live Alone” is unusually happy for being a chronicle of a woman who’s man “don’t pay no mind to me” and who laments the futility of a houseful of material gains when there’s no love around—it’s as if the “old man magnet” has gone down in flames. Which does happen, and thus is true to the blues being about life. A couple of tracks later, in her cover of the vintage 1960 Jon Thomas R&B gem. “Heartbreak,” the singer is completely bereft of male companionship, physically abject (“I’m weak in the knees, loose in the head, my baby done left me, I wish that I was dead”), feeling double-crossed by her beau but admitting she would be back in his arms in a hot minute if he showed up again. Playing out at a cool, measured pace, the arrangement cruises along on a smooth groove supported by Linda Dachtyl’s rich B3 ballast. In a profoundly spiritual moment, Ms. Tucker offers a deliberate, gospel-inflected reading of her and Hughes’s affecting country blues tribute to the late Piedmont blues master “John Cephas” (of Cephas & Wiggins), backed only by Hughes’s acoustic guitar, a hearty female backing chorus and Gastel’s harmonica, wafting ethereally through the latter part of the song. In her closing summation, Ms. Tucker, with only Hughes’s evocative electric guitar behind her, both speaks and sings her closing supplication, a quiet, determined, self-explanatory “Respect Me and The Blues.” She doesn’t drive a hard bargain—even acknowledging how one person’s preference for this or that might be countered by another’s for that or this (put another way, you say tomato, I say tom-ah-to)—but in the end, after everything that has transpired on these eleven cuts, you say, “Yes ma’m, whatever you say, ma’m. I’m with you all the way.” It’s the right thing to do.

Teeny Tucker’s Keep The Blues Alive is available at www.amazon.com

Tommy Tucker, Teeny’s dad, in his indelible moment: ‘Hi-Heel Sneakers’ (1964, #11 pop)

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024