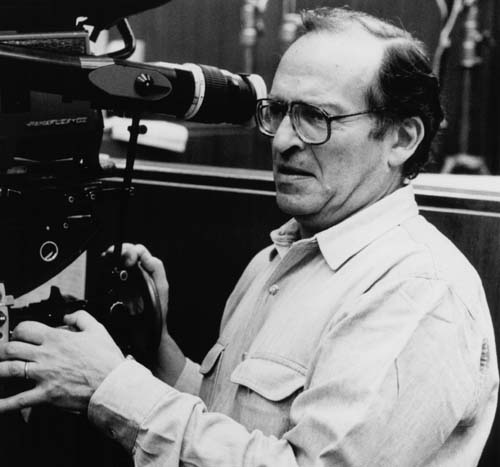

Sidney Lumet: ‘…any script that starts in New York has got a head start.’Remembering Sidney Lumet

‘The City Can Become Anything You Want It To Be’

The script for Sidney Lumet's own life, the one he directed every day, was written 2,000 years before his birth by the historic sage, Rabbi Hillel.

"If I am not for myself, who will be for me? If I am not for others, what am I? And if not now, when?"

Sidney Lumet, June 25, 1925 - April 9, 2011.

Rest in Peace.

Seth Eisenberg, President/CEO of PAIRS Foundation, an industry leader in relationship and marriage education.

"Sidney Lumet: Last of the Great Movie Moralists"Sidney Lumet, as quintessential a New York filmmaker as his friend and contemporary Woody Allen, directed more than 50 movies, was nominated for an Academy Award four times, but earned only a Lifetime Achievement Award, given him in 2005. “I guess I’d like to thank the movies,” he said in accepting his lone aaward.

Actors in Lumet movies, however, were nominated for 17 Oscars for their performances. He preferred it that way, letting others get the acclaim while he tried to remain, as he put it, “invisible” in the film. Even so, Lumet was ever present in his movies. In his great humanity, his sense of social justice, and his frustrations with bullheaded authoritarian intractability and his refusal to tolerate it, he was an everyman voice comparable to the great directors of his time. In Network, Serpico, Dog Day Afternoon, 12 Angry Men, Prince of the City or any of the other stirring movies on his resume, he let his work--and he always referred to his films as "work"--speak for his noble character, Lumet did exactly what he hoped to do with a script--allow the issues it raised, not his directorial flair in realizing the ideas on screen, be the story, the center of debate, the mirror held up to a chaotic society sometimes gone frightfully astray morally, ethically and spiritually. Raised as an actor and molded in live television, he was a pragmatic director, eschewing ostentatious displays of style for sure-handed storytelling.

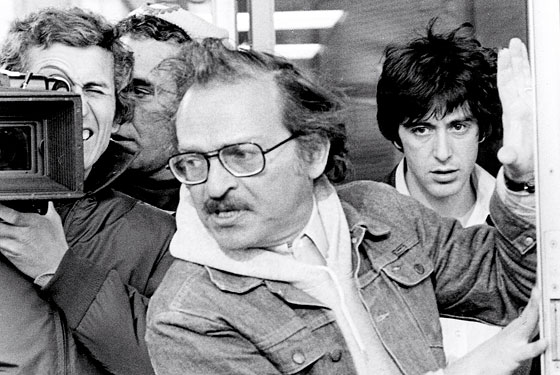

Sidney Lumet and Al Pacino, shooting Dog Day AfternoonWhen Martin Scorsese mourned Lumet's death--in New York on April 9, from lymphoma--as "the end of an era," you wanted to believe he was overstating the case. When you cued up a Lument film, though, you felt the weight of Scorsese's convictions. Sidney Lumet's death was indeed the end of an era.

In a 2006 interview from his office above the Broadway theaters where he performed as a child, Lumet was typically unpretentious in discussing his films, a body of work numbering more American classics than most have a right to contemplate.

"God knows I've got no complaints about my career," Lumet said. "I've had a very good time and gotten some very good work done."

He rarely did more than two or three takes and usually cut "in the camera"--essentially editing while shooting--yet his efficient ways captured some of the greatest performances in American cinema: Al Pacino as Sonny Wortzik in Dog Day Afternoon, Peter Finch as Howard Beale in Network, Paul Newman as Frank Galvin in The Verdict.

A deeply moral filmmaker, Lumet often made films crackling with social justice. His first feature film, 1957's 12 Angry Men, used the plodding reason of Juror no. 8, played by Henry Fonda, to overturn the prejudices and assumptions of his follow jurors. His 1964 film The Pawnbroker was one of the early U.S. dramas about the Holocaust. His Fail-Safe, also from 1964, was a frightening warning about nuclear bombs.

12 Angry Men, directed by Sidney Lumet: using the plodding reasoning of Juror no. 8, played by Henry Fonda (second from left) to overturn the prejudices and assumptions of his follow jurors.He was always closely associated with New York, where he shot many of his films, working far from Hollywood. The city was frequently a character in its own right in his films, from the crowds chanting "Attica!" on the hot city streets of Dog Day Afternoon to the hard lives and corruptibility of New York police officers in Serpico, Prince of the City and Q&A.

"It's not an anti-L.A. thing," Lumet said of his New York favoritism in a 1997 interview. "I just don't like a company town."

"I'm constantly amazed at how many films of his prodigious output were wonderful and how many actors and actresses had their best work under his direction," Woody Allen said in reflecting on Lumet’s career. "Knowing Sidney, he will have more energy dead than most live people."

Scorsese said Lumet "was a New York filmmaker at heart, and our vision of the city has been enhanced and deepened by classics like Serpico, Dog Day Afternoon and, above all, the remarkable Prince of the City."

He said it would be difficult to imagine "there won't be any more new pictures by Sidney Lumet.”

"All the more reason," he added, "to take good care of the ones he left behind."

‘Attica! Attica!’ A classic scene from Dog Day AfternoonLumet once claimed he didn't seek out New York-based projects. "But any script that starts in New York has got a head start," he said in 1999. "It's a fact the city can become anything you want it to be."

Lumet remained active into his 80s, saying he wasn't geared for retirement and couldn't imagine giving up the life of making movies. His last film was 2007's Before the Devil Knows You're Dead. "He was a true master who loved directing and working with actors like no other," said Phillip Seymour Hoffman, who starred in it. "He was and is valuable on so many levels the thought itself overwhelms. I adored him. God, we're going to miss him."

The director was born June 25, 1924, in Philadelphia to a pair of Yiddish stage performers, and he began his show business career as a child actor, appearing on radio at age 4.

He made his Broadway debut in 1934 with a small role in Sidney Kingsley's acclaimed Dead End, and he twice played Jesus, in Max Reinhardt's production of The Eternal Road and Maxwell Anderson's Journey to Jerusalem.

Prince of the City (1981), starring Treat Williams and Jerry OrbachAfter serving as a radar repairman in India and Burma during World War II, Lumet returned to New York and formed an acting company. In 1950, Yul Brynner, a friend and a director at CBS-TV, invited him to join the network as an assistant director. Soon he rose to director, working on 150 episodes of the Danger thriller and other series.

The advent of live TV dramas boosted Lumet's reputation. He directed the historical re-enactment program You Are There, hosted by Walter Cronkite. Like Arthur Penn, John Frankenheimer, Delbert Mann and other directors of television drama's Golden Age, he transitioned to feature filmmaking.

Later, when Lumet directed the 1976 TV news satire Network, penned by Paddy Chayefsky, he would winkingly insist the dark tragicomedy wasn't an exaggeration of the TV business but mere "reportage." The film proved to be Lumet's most memorable and created an enduring catch phrase. The crazed newscaster Howard Beale --"the first known instance of a man who was killed because of lousy ratings"--exhorts people in his audience to raise their windows and shout: "I'm mad as hell, and I'm not going to take it anymore!"

Beale is ultimately assassinated by his network bosses (Faye Dunaway, Robert Duvall) on live television. Lumet called such a scene--the live broadcast of a murder--"the only part of Network that hasn't happened yet, and that's on its way."

The film was nominated for 10 Academy awards and won four.

‘I’m mad as hell and I’m not gonna take this anymore! Then we’ll figure out what to do about the depression and the inflation and the oil prices…’ Howard Beale’s prescient rant in Network (1976). Script by Paddy Chayefsky.Lumet immediately established himself as an A-list director with 12 Angry Men, which took an early and powerful look at racial prejudice as it depicted 12 jurors trying to reach a verdict in a trial involving a young Hispanic man wrongly accused of murder. It garnered him his first Academy Award nomination.

His other nominations were for directing Network, Dog Day Afternoon (1975) and The Verdict and for his screenplay adaptation for 1981's Prince of the City.

"I'm also not a competitive man, but on two occasions I got so pissed off about what beat us," he later said. "With Network, we were beaten out by Rocky, for Christ's sake."

That year, the field also included Taxi Driver and All the President's Men. The Verdict lost to Gandhi in 1983, a year in which E.T. also finished as an also-ran.

Early on, Lumet showed a nimbleness in material and a reluctance for showy directing. In his 1995 filmmaking guide Making Movies, he called style "the most misused word since love.”

"Good style is unseen style," wrote Lumet. "It is style that is felt."

Although Lumet was best known for his hard-bitten portrayals of urban life, his resume also includes some of the finest film adaptations of noted plays: Eugene O'Neill's Long Day's Journey into Night, Arthur Miller's A View from the Bridge, Chekhov's The Sea Gull and Tennessee Williams' Orpheus Descending, which was made into The Fugitive Kind, starring Marlon Brando.

In an interview with director Peter Bogdanovich, Lumet compared filmmaking to "making a mosaic.

"You take each little tile and polish and color it, and you just do the best you can on each little individual tile, and it's not until you've literally glued them all together that you know whether or not you've got something good," he said.

Some did not turn out well, such as 1992's A Stranger Among Us, with Melanie Griffith, and one of film’s great bombs, 1978's The Wiz, an ill-advised adaptation of The Wizard of Oz featuring black actors.

‘Wherever you run into it, prejudice always obscures the truth’: 12 Angry Men (1957)The composer Quincy Jones, who got his start in movies with Lumet’s The Pawnbroker and scored music for five of Lumet's films, said news of the director’s death devastated him.

"Sidney was a visionary filmmaker whose movies made an indelible mark on our popular culture with their stirring commentary on our society," Jones said. "Future generations of filmmakers will look to Sidney's work for guidance and inspiration, but there will never be another who comes close to him."

Lumet received the Directors Guild of America's prestigious D.W. Griffith Award for lifetime achievement in 1993.

Pacino, who produced memorable performances for Lumet in Dog Day Afternoon and Serpico, introduced the director at the 2005 Academy Awards. "If you prayed to inhabit a character, Sidney was the priest who listened to your prayers, helped make them come true," the actor said.

Other popular Lumet films included Running On Empty and Murder on the Orient Express.

In 2001 he returned to his television roots, creating, writing, directing and executive producing a cable series, 100 Centre Street, filmed in his beloved New York.

‘How come you people come to business so naturally?’ ‘You people?’: The Pawnbroker (1964), with Rod Steiger and Brock Peters.Generally, Lumet fared well with the critics, save for The New Yorker’s Pauline Kael, the most powerful film critic of her time. She rarely found much to praise in Lumet’s movies. Of The Verdict, she wrote: “Directed by Sidney Lumet from a script by David Mamet that derives from a novel by Barry Reed, the movie is so impressed by its own high seriousness that it has a hushed atmosphere. It strives for gloom.” Later she observes: “When Lumet gets serious, his energetic, fast-moving style falls apart, and he photographs scenes from fifty yards away. The camera just sits like Death on these dark, angled images. Lest anybody miss the point, Lumet puts dirges on the soundtrack.” She was especially critical of his handling of Serpico: “Once again, Lumet brought a picture in ahead of schedule, although scene after ragged scene cried out for retakes. ‘He completed the film in ten weeks and one day--incredible, considering the logistics,” the publicity boasts, as if making a film were a race and the speedy Lumet the champ. He wins the prize this time, because the cynical, raw but witty script is right for him and he gives the material the push it needs. But, except for Pacino, almost all the casting seems aberrant, and the actors playing smaller roles--there are around thirty of them--suffer, since they can’t direct themselves and work out a conception when they’re on for only a scene or two.”

Lumet's first three marriages--to actress Rita Gam, heiress Gloria Vanderbilt and Lena Horne's daughter, Gail Jones--ended in divorce In 1980, he married journalist Mary Gimbel.

He is survived by his wife, daughters Jenny and Amy Lumet, stepchildren Leslie and Bailey Gimbel, nine grandchildren and a great-granddaughter. Amy Lumet also works in the film business, as a sound editor.

***

Jane Fonda Remembers 'Kind And Generous' Sidney Lumet

Veteran actress Jane Fonda has paid a touching tribute to legendary Hollywood filmmaker Sidney Lumet, calling him "a master" of movies.

The actress worked with Lumet on 1986 drama The Morning After and she's praised the "strong, progressive" director/producer for being so "kind and generous" towards her.

In a post on her blog, Fonda writes, "Sidney's first film, 12 Angry Men, was the only film my father ever produced. I saw it again fairly recently and realized what a brilliant film it is. I also worked with Sidney in The Morning After in which I played a drunk. I loved working with him. He was a master. Such control of his craft. He had strong, progressive values and never betrayed them.

"Alongside that, he loved to laugh. I remember when I first met him... way back in the late ‘50s when he was working with my Dad, I was struck by his laughter. He taught me to appreciate bagels... good New York bagels.

"He was always very kind and generous with me and I am very sad he has died."

Contactmusic.com, April 11, 2011

***

Sidney Lumet: In Memory

By Roger Ebert

Excerpt from his April 9, 2011 column at rogerebert.com

Of his final film, Before the Devil Knows You're Dead (2007), I wrote: "This is a movie, I promise you, that grabs you and won't let you think of anything else. It's wonderful when a director like Lumet wins a Lifetime Achievement Oscar at 80, and three years later makes one of his greatest achievements." Like many of his films, it went on my list of the year's ten best.

Although he was not as widely known to the general public as directors like Scorsese, Spielberg, Eastwood and Spike Lee, his films were at the center of our collective memories. To name only a few of their titles is to suggest the measure of his gift: Network. Dog Day Afternoon. 12 Angry Men. Serpico. Prince of the City. The Pawnbroker. Fail-Safe. Long Day's Journey into Night. The Verdict.

Most of his films were set in his native New York City. Although he was nominated four times as best director, he never won an Academy award until his honorary Oscar; that may have been partly because he was not part of the Hollywood community but preferred a milieu he understood inside-out.

He was a thoughtful director, who gathered the best collaborators he could find and channeled their resources into a focused vision. He shared his thoughts about that in his 1996 book Making Movies. If you care to read only one book about the steps in the making of a film, make it that one. There is not a boast in it, not a word of idle puffery. It is all about the work.

To say he lacked a noticeable visual style is a compliment. He reduced every scene to its necessary elements, and filmed them, he liked to say, "invisibly." You should not be thinking about the camera. He wanted you to think about the characters and the story.

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024