Everything’s Jake

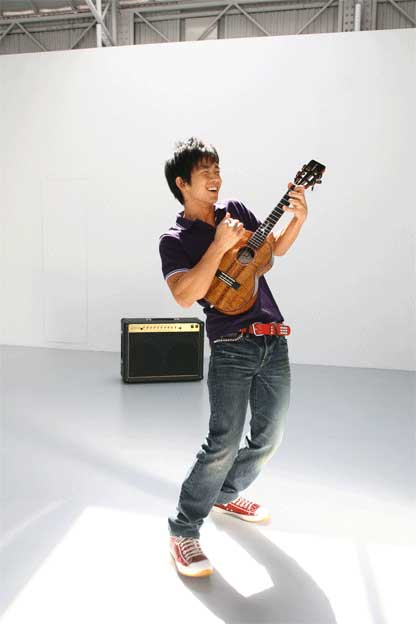

Hawaiian-born Jake Shimabukuro Finds Vitality, And a Career, In the Ukulele

By David McGee

That Jake Shimabukuro is a coy one. Currently on tour as a member of Jimmy Buffett's band, the native Hawaiian (born of Japanese-American parents) has found his career on a steadily ascending arc following a December 2005 performance on The Late Show with Conan O’Brien that found him fashioning a stunning, sensitive exploration of George Harrison’s “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” on his instrument of choice, the ukulele. As a result of this first appearance on national TV, Shimabukuro has brought the ukulele (which he pronounces properly as “ooo-koo-lay-lee”) a measure of prominence it hasn’t enjoyed since the late ‘60s emergence of Tiny Tim, who became its most notorious (and most underrated) practitioner since the heyday of Arthur Godfrey in the 1950s.

But neither Mr. Tim nor Mr. Godfrey explored the ukulele’s tonal and expressive landscape. Rather, both used the instrument in an accompanying capacity, strumming chords behind their vocals. Shimabukuro is introducing audiences to the serious side of ukulele artistry, which has a long and illustrious history in Hawaii but has been largely hidden from mainlanders.

And yet, when asked to name other ukulele masters who have inspired him since he began plucking away at the age of four, Shimabukuro is vague in citing influences but specific in pinpointing lessons learned from other sources.

“It pretty much comes from everyone,” says the affable Shimabukuro (who speaks in the energetic, faintly flabbergasted tone of one who cannot believe his good fortune), identifying his roots as being in traditional Hawaiian music without naming anyone in particular. “I listened to a lot of other ukulele players in Hawaii, but as I got older, especially when I was a teenager, I realized I could learn from other musicians—not just ukulele players, but from guitar players, from horn players, string players, piano players, singers, drummers. I could learn something from all these different players. And apart from musicians, I can learn from athletes and anyone that has a passion for some kind of art form—dancers—all of these I can learn from. One of my biggest heroes and influences was Bruce Lee, his philosophy and the way he approached his martial arts. I applied a lot of his philosophy and concepts and ideas towards playing the ukulele. Even athletes, like Michael Jordan, Joe Montana, just the way they’re able to focus and get in the zone; the level of concentration utilizes the whole body. Even though I play the ukulele, it’s not just about my fingers and my hands and my arms; it’s about getting up on the balls of my feet and feeling that energy from my feet coming up through my hips and my back, all of those things. I do realize that you use your entire body to create sound. I just thought that was so fascinating. So basically I would just study a lot of different people who were passionate about something or were really good at something. I studied them and did research on them, and if I had the opportunity I would interview them, ask them questions. Yeah, that was the best thing for me in pursuing my instrument.”

However, Shimabukuro’s catalogue contains all kinds of clues pointing to his embrace of his home state’s rich musical history as it relates to the ukulele even as it shows him advancing it to a degree the old masters surely find pleasing. Go back to his striking 2002 album, Sunday Morning, and check out his near-four-minute inspection of Puccini’s “Caprice No. 24,” a piece written for violin. First, you’ll be struck by how much the angular, speed-picked passages resemble a mandolin solo as Chris Thile might construct it, right down to the uke itself sounding like a mandolin. Then you’ll hear bent notes right out of a blues solo; and a most effective, even riveting, use of silence to augment the reflective mood. In and of itself, this performance links Shimabukuro to two of the great visionary masters of the ukulele, Eddie Kamae and his one-time student, Herb “Ohta-San” Ohta, who in the 1960s ventured into previously uncharted territory for uke players in reimagining Latin, jazz, classic American pop, ragtime and classical as showcases for ukulele virtuosity.

And though one wag, after witnessing the physicality of a Shimabukuro performance (the artist is not kidding when he talks about using his entire body to create sound), dubbed him “the Jimi Hendrix of the ukulele,” Shimabukuro responded in a more subtle way: On his most recent album, 2006’s Gently Weeps (which contains the aforementioned and now much celebrated interpretation of “While My Guitar Gently Weeps”), he offers “The Star Spangled Banner.” Ah, but instead of Hendrix-like sturm und drang, Shimabukuro takes it in a more restrained, decidedly unbombastic direction in which the energy stays at mid-flame, threatening to erupt before receding into measured, respectful, melodic ruminations honoring the song’s sentiment while illuminating some often overlooked subtleties in the arrangement. Here, though, is a patriotic moment that has its roots even deeper in Hawaiian music, going back to the revered Jesse Kalima’s exuberant, bluegrass-style 1946 recording of John Philip Sousa’s “Stars and Stripes Forever.”

So on some level Shimabukuro, who was born on November 3, 1976 and looks considerably younger than his meager years, knows more than he lets on in conversation but not when he plays. That’s when the real Shimabukuro magic happens, because his are performances that can be enjoyed whether one is engaging with the history informing the method, the exhilarating musicianship, or the entrancing mood conjured in deeply introspective interpretations.

Shimabukuro rose to prominence in Hawaii in 1998 as a member of a multiple award winning trio called Pure Heart, which played in a contemporary style likened to that of the popular Ka’au Crater Boys, a duo whose exceptional uke player, Troy Fernandez, brought a wealth of influences to bear on his style, including country, and whose repertoire embraced traditional Hawaiian numbers, reggae, country, rock, pop (the Cascades’ 1963 hit, “Rhythm of The Rain,” was a fan favorite), Dylan (“I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight”), Clapton (“Lay Down Sally”), Van Morrison (“Brown Eyed Girl”), et al. When Pure Heart lost its guitar player Jon Yamasato (he served noticed of his departure in a story published in a local newspaper), Shimabukuro and percussionist Lopaka Colon recruited guitarist Guy Cruz (younger brother of the Ka’au Crater Boys’s guitarist Ernie Cruz, Jr.) and named the group Colon in honor of Lopaka’s revered percussionist father, Augie Colon. After Colon won an award as Entertainer of the Year in 2001, Shimabukuro split to pursue a solo career. He released his first album, the aforementioned Sunday Morning, in 2002; four others have followed, as well as a soundtrack for the film Hula Girls (released last year, the movie was a smash hit in Japan).

His most recent recording is a six-song EP, My Life, which features two more Beatles covers—the lovely title track and, from the Revolver album, “Here, There and Everywhere”—as well as a frenetic, frailing rendition of Robert Plant-Jimmy Page’s “Going to California,” an impressionistic take on “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” that owes more to Debussy than to Arlen and Harburg (or Judy Garland, for that matter), a caressing, lullaby-style sign-off on Sarah McLachlan’s “Ice Cream,” and a seductive, swaying introductory rendition of Cyndi Lauper’s “Time After Time,” featuring Jake’s brother Bruce on guitar as well as percussionist Tamao Fujii, a rare ensemble foray for Shimabukuro but one that lends a captivating ambiance to the entire endeavor.

So it’s unsurprising when Shimabukuro says, “I love all styles of music,” more so when he adds: “I can do a little bit here and there, but I can’t do any one style really well.

“But I like to dabble a little bit, a little bit of jazz, some classical, some rock pieces and all of that,” he adds. “I enjoy it. When I listen to my iPod, my playlist will go from Brazilian jazz to classical to Japanese music, to fusion stuff, or really heavy metal. That keeps it interesting for me. Hopefully when I do concerts, the audience feels the same way, going from a bluegrass piece to ‘Ava Maria’ to a traditional Japanese folk tune and from that to George Harrison’s ‘While My Guitar Gently Weeps.’ With every song you cleanse your palette for the next round.

“When I perform, I treat every song as if it’s its own thing. I’ve talked to many people about this, about how they approach their performance. Everybody does it differently. Some artists will look at their concert and set up a set list as one whole song. You can kind of program it that way, dynamically and all that. I’ve always taken the approach that if I’m doing 15 or 20 songs, I try to treat each one as if it’s its own mini-show. It works nicely that way. I find it comfortable because the styles are so diverse. It’s fun.”

But if any one thing stands out from his recorded work so far, it’s an emphasis on melody. Some artists don’t fear making music sound ugly, so to speak, but Shimabukuro first looks for a memorable melody, and then takes it to other places. “For me, melody is huge. It’s definitely what my ears always gravitate towards. When I turn on the radio, I’m always listening to what the lead melody’s doing, or a melodic bass line, I’m always drawn to that. And that probably has a lot to do with the music I choose to cover—there’s something in the melody that I really enjoy playing. And just finding interesting ways to execute them on the ukulele. That’s always fun, challenging and fulfilling.”

My Life turns out to be a bit of a stopgap between Gently Weeps and the next studio album, while Shimabukuro (who has played just about every important venue in the U.S. and been on three different tours with Bela Fleck & the Flecktones over the years) takes advantage of his growing acclaim by hitting the road for awhile. One wonders if he has any concern over the impassioned reaction to the softer, easier listening numbers overshadowing the complexity and inventiveness marking less celebrated items his repertoire.

“I never thought of it that way,” he answers immediately. “I just try to have fun and I try to connect with the audience as much as I can, be sensitive to what I think the audience is feeling. I almost think of the audience as my band members. So even though I’m performing solo on stage, I feel they contribute just as much to a performance as I do. So it’s trying to understand their energy, and reading them and kind of interacting with them—that’s a huge part of the performance. It’s the same as if I had a rhythm section on stage with me, a drummer and a bassist, I’d be doing the same thing. When we’re playing together you’re really trying to home in on what they’re doing and what they’re feeling and the dynamics of their performance. You want to be as sensitive to that as possible so that everyone plays together. It’s really a conversation, and I try to have that same conversation with the audience.”

Still, Shimabukuro admits to a long-term plan to start bringing more of his own songs to the party, beginning with the album he’ll start working on after the touring season.

“I’ve been writing songs here and there. I’ve never done a full album of all originals yet. I’m hoping to do that for my next release. I’ve been spending a lot of time recently just writing and coming up with new material, so I’m really hoping this next release, some time late this year or early next year, will be all original tunes.”

As for the attention that’s come his way in such a rush this year, he’s still trying to take it all in, saying he “can’t believe all these wonderful opportunities and experiences I’ve been having. It’s such a blessing. And for me, I just love music, and I love learning more about different things and being able to travel and tour, play with other musicians, meet other musicians. It’s been the best education for me. That’s what I’m loving so much, just being a part of everything that’s happening, with other artists and just music in general. It’s really exciting. I just want to keep doing that, keep challenging myself, keep learning new things.”

And when the grind of the tour is over, guess where Jake Shimabukuro goes? Home to Hawaii. Think about it.

“Yeah,” he says with a knowing laugh. “Usually it’s the other way around. People go to Hawaii for vacation and at the end of their travels they go back to wherever. For me, at the end of my travels I get to go back to the place where everybody else goes for vacation. Really nice.”

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024