Crossing Over

by David McGee

***

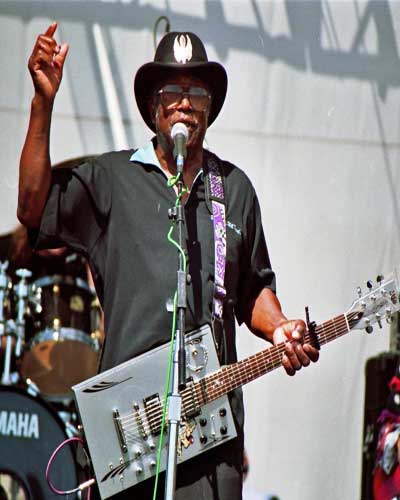

Bo Diddley

Bo Diddley, one of rock ‘n’ roll’s founding fathers, architect of its most primal and most imitated beat, died of heart failure on June 2 at his home in Archer, FL. Diddley had been in failing health for several years, and had suffered both a stroke and a heart attack in 2007. Born Ellas Otha Bates in McComb, MS, he was raised by Gussie McDaniel, his mother’s first cousin. After the death of her husband, Ms. McDaniel took Ellas and her three children to live in Chicago. She became his legal guardian and his name was changed to Ellas B. McDaniel. As child he studied classical violin from ages seven to 15 and began learning guitar at age 12. He played in a band and orchestra led by O.W. Frederick, a music teacher at Ebeneezer Baptist Church. Enrolling at Foster Vocational School, he began building is own instruments—a guitar, a violin and an upright bass. Dropping out of school to pursue music professionally, he formed a band, the Jive Cats, with his friend Roosevelt Jackson (washtub bass) and guitarist Jody Williams, with harmonica player Billy Boy Arnold later coming on board. To support his musical endeavors, McDaniel generated income from a variety of sources—as a boxer, elevator operator, manual laborer, among other short-lived occupations.

When the Jive Cats’ popularity earned the band club dates, McDaniel started developing a distinctive sound. He built a powerful amplifier out of old radio parts, and the addition of maracas player Jerome Green brought a restless, Latin-tinged shuffle sound to the mix. At this time he was also writing, prolifically and, sometimes, profanely, but always good naturedly. With a new band lineup, he recorded a two-song home demo tape in the fall of 1954, featuring two original tunes, the slightly ribald “Uncle John” and a boastful “I’m a Man.” Two Chicago record companies turned it down, but brothers Leonard and Phil Chess, of Chess Records, heard the originality in McDaniel’s music and called him in to re-record the songs in a professional studio. At the end of the “Uncle John” session, the name Ellas McDaniel was consigned to history and the young man with the infectious beat was known as Bo Diddley, after the like-titled song that had been known as “Uncle John” when the session started.

The origins of the name Bo Diddley remain cloudy, and even Bo himself told several variations of it. But the most credible version comes from Billy Boy Arnold, as recounted in Nadine Cohodas’s definitive history of Chess Records, Spinning Blues Into Gold: The Chess Brothers and the Legendary Chess Records (St. Martin’s Press, 2000). According to Arnold, Leonard Chess demanded a new name for the group and revised lyrics for “Uncle John” that would make it more palatable for older audiences and especially for radio. Arnold says he had recalled seeing a street clown who called himself “Bo Diddley,” and suggested Ellas adopt the name. Leonard was uncertain about it, but urged the group to continue working on a re-tooled version of “Uncle John” with the same rhythm. McDaniel’s rewritten lyrics began, “Bo Diddley bought his baby a diamond ring…” The final version was cut on March 2, 1955, with a combo that included the great blues piano player Otis Spann joining McDaniel, Arnold, bassist James Bradford, drummer Clifton James and Jerome Green on maracas. According to Cohodas’s account, the “Bo Diddley” session was long and tedious, especially for Leonard Chess, who instructed McDaniel where to play his solo and insisted he turn up the tremelo on his amplifier. Finally, impatient with the artist’s vocal, he needled him to “sing like a man! The beat has got to move at all times.” A similar tension informed the session for “I’m a Man,” on which Willie Dixon had been brought in to play bass. It was Chess’s idea for McDaniel to spell out the word “man,” and he made him do it several times, each take finding McDaniel increasingly fuming, until he finally exploded and spat out the letters with searing fury—exactly as Chess had anticipated.

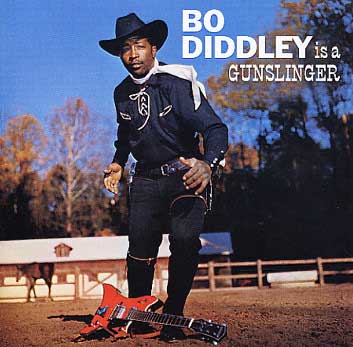

Bo Diddley, as McDaniel would forever be known, took a simple shave-and-a-haircut-six-bits rhythm and embellished it with layer upon layer of rhythmic variation, courtesy Green's maracas and his own heavily tremeloed guitar on which he played two different rhythms simultaneously. Having created form, he added complexity in myriad harmonic and textural conceits. He brought his world to life in song by blending gospel and blues, then spicing these bedrock ingredients with quotes from black street-corner culture ("Say Man" being an early example of Diddley's use of "the dozens," ritualized insults, boasts and dares). Bringing it all home in a deep, confident baritone vocal strut, Diddley became the absolute ruler of his dominion, an artist whose sound remains a touchstone for rock ‘n’ roll guitarists and percussionists, and whose standing as "500 percent more man," as he asserted in one of his memorable lyric flights, remained unassailed at his death. For all this acclaim and influence, Diddley had only one national Top 40 hit, 1959’s genial novelty, "Say Man," on which he traded insults with Jerome Green, but his enduring influence on the music he helped pioneer was undeniable—the Rolling Stones practically built their early career on the Bo Diddley beat, and before them Buddy Holly was fairly brazen in co-opting it for his own purposes. Diddley produced a wealth of catalogue for Chess before his contract expired in 1974, and the best of it has been boiled down to a few essential multi-disc CDs, notably the double-CD The Chess Box, and the more recent overview, I’m a Man: The Chess Masters, 1955-1958. Blessedly returned to print in an expanded edition is one of his greatest Chess albums, Bo Diddley Is a Gunslinger, which features the artist attired in a cowboy outfit, outside a horse stable, with one of his distinctively shaped guitars at his feet as he reaches for his gun. The album is fast and furious, and includes Diddley doing a unique interpretation of labelmate Chuck Berry’s style on “Ride On, Josephine” (which opens with a riff Lonnie Mack later copped for his hit instrumental version of Berry’s “Memphis”) as well as streamrolling his way through Merle Travis’s “Sixteen Tons” with one of his most menacing vocals on record.

In the early ‘90s Diddley found a home on Triple X Records and Code Blue/Atlantic, and although there were some gems along the way, the bulk of these recordings is lamentable, to be charitable, with his guitar and even his comical self-aggrandizing downplayed in favor of ill-considered social commentary and what sound like desperate attempts to update his sound with ill-fitting hip-hop and electronic flourishes. He reached a low point on his 1994 Promises album, when, in the song “She Wasn’t Raped,” he trots out the repugnant, disingenuous formulation “she gave it up,” like a sleazy defense attorney trying to blame the victim for being sexually assaulted. He also found a second calling complaining about royalties he claimed were owed him, and even suggested that artists who used his beat owed him money. In her research on the Chess story, however, Cohodas found that the Chess brothers had loaned Diddley, and many of their artists, money as advances against royalties, some of which Diddley used to build a recording studio in his home in Washington, D.C. A bitter Diddley declared his deal with Chess to be a “CON-tract.” But he’s also on record as being generous in his appraisal of his Chess tenure, telling Blues Unlimited in a 1969 interview, “I feel that we were like a family. This is the way I felt. I felt I was for them and they was for me and we were for each other.” Startled by Diddley’s vitriolic attacks on him and his brother, Phil Chess said Diddley “always seemed to me like he was happy,” and Etta James told Cohodas, “When I was there with Leonard, God, Leonard treated Bo like some kind of royalty.”

Cohodas determined that “without documents—Bo Diddley’s contracts, the sales figures for his records, the costs to make the records, and the advances he may have received—the accuracy of Diddley’s allegations were difficult to judge. But his anger reflected the view among some musicians that they were cheated, an allegation steadfastly denied by Phil and Marshall (Chess, Leonard’s son). ‘What’s missing from Bo’s version of events,’ Marshall insisted, ‘is all the gimmes. Bo was one of the biggest takers.’ In those early years,’ he said, ‘it was a constant refrain of ‘I need, I want’—five hundred dollars at a clip that could add up to thousands by the end of the year.’”

Where the money went, if it went anywhere at all, may always remain a bone of contention in the Bo Diddley story. But the beat…the beat goes on.

***

DOTTIE RAMBO

One of the great gospel songwriters of contemporary times, Dottie Rambo, died on May 11 of injuries sustained when her tour bus ran off the highway near Mount Vernon, MO, as she was en route to a Mother’s Day show in Texas. She was 74.

Born into poverty in Madisonville, KY, on March 2, 1934, at the height of the Depression, she learned to play guitar by listening to musicians on the Grand Ole Opry radio show; at age eight she started writing songs, and two years later she was performing on a local radio show. At age 12 she became a born-again Christian and vowed to devote her life to writing and singing Christian music—which so angered her father that he demanded she either give up Christian music or move out of the house. She left home and started working on the road, first at a church in Indianapolis, IN, and then throughout the Midwestern and southern states with a trio she formed called the Gospel Echoes. At age 16, she met another gospel singer, Buck Rambo, at a revival meeting, and they were soon married and performing together as the “Singing Rambos,” later shortened to “The Rambos.” In 1952 she gave birth to a daughter, Reba, who began performing with her parents when she was 12.

The Rambos’ first big break came when Jimmie Davis, then the governor of Louisiana but a country music giant on the strength of his song “You Are My Sunshine,” signed Dottie to a publishing deal. Her songs gained enough notice that Warner Bros. Records signed her to a recording contract. Although initially influenced by traditional country music, Rambo had an affinity for black gospel and seamlessly blended both styles into her original songs, an approach that reached fruition with her 1968 Grammy Award for Best Soul Gospel Performance for her album It’s the Soul of Me. The Rambos also played for soldiers in Vietnam in 1967, visiting field hospitals and battleships along their route. Eventually she left the Warner Bros. fold and began a long association with Benson Records and its Heartwarming label.

Estimates of Rambo’s songwriting output range from 700 to 2,500 songs. What’s not in dispute is the wide variety of artists who recorded her songs, from a veritable Who’s Who of Country Music Hall of Fame artists or future inductees to mainstream pop stars (Carol Channing recorded Rambo’s “One More Valley”) to black and white gospel groups and solo artists (Andrae Crouch to the Imperials to Jessy Dixon to the Oak Ridge Boys, et al.) to Elvis Presley, a major fan of Rambo’s work. A handful of the gospel standards she penned include “We Shall Behold Him,” “Sheltered Arms of God,” “Tears Will Never Stain the Streets of That City,” “If That Isn’t Love” and “I Will Glory in the Cross.”

In 1989, two years after a back injury had left her left leg partially paralyzed, Rambo retired; in the following decade her marriage to Buck Rambo ended in divorce. But she returned in 2003 with a hit duet with Dolly Parton, “Stand By the River,” and began touring again, playing as many as 150 dates a year. She was duly recognized for her achievements with numerous honors, including induction into the Gospel Hall of Fame (twice, with the Rambos and as a solo artist), a Songwriter of the Century Award from the Christian Country Music Association in 1994, an ASCAP Lifetime Achievement Award in 2000, a Gospel Music Association Dove Award in 1999 for her song “I Go To the Rock,” performed by Whitney Houston in the film The Preacher’s Wife, induction into the Kentucky Music Hall of Fame in 2006, and, at the time of her death, election to the Christian Music Hall of Fame, where she was to be formally inducted on June 14.

Her daughter Reba Rambo-McGuire survives her, along with a sister, two brothers, three grandchildren and one great-grandchild.

***

TIM RUSSERT

NBC News Washington Bureau Chief and host for more than 16 years of the Sunday morning news show Meet the Press, Tim Russert collapsed and died in the offices of WRC-TV while recording voiceovers for his next Sunday show. He was 58. Cause of death was determined to be sudden cardiac arrest. A devoted family man, a devout Catholic and an indefatigable reporter whose devotion to research and facts was all consuming, Russert set the bar high for journalists in every field—not impossibly high, but right where it should be on a scale of truly fair and balanced reporting that was real, not merely a slogan conveniently ignored when the facts don’t fit a presupposition or a specific ideology. In this most critical of election years, his insight, empathy, compassion, and political savvy will be sorely missed. Business Week’s David Kiley put it best, saying, “This year’s election will still be historic. But we sadly lost our best real-time historian to describe it for us.” Russert is survived by his wife, Maureen Orth, a special correspondent for Vanity Fair; a son, Luke, newly graduated from Boston College; three sisters; and his beloved father, Tim, or “Big Russ,” the subject of his son’s best selling 2004 book, Big Russ and Me, a work that resulted in 60,000 letters to the author from readers reflecting on their own experiences with their fathers; these then formed the foundation for a best selling sequel in 2006, Wisdom of Our Fathers: Lessons and Letters from Daughters and Sons.

***

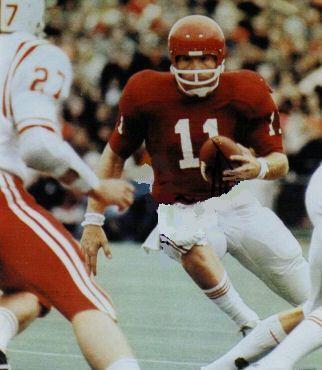

Jack Mildren

One of the greatest college football quarterbacks of all-time and recognized as “the Godfather of the Wishbone offense,” Jack Mildren succumbed to a two-year battle with stomach cancer on May 22. He was 58. Born in Kingsville, TX, Mildren came to the University of Oklahoma as one of the highest touted players in the country. At the annual intra-squad freshman game in 1968 (freshmen were not allowed to play varsity sports in those days), which was usually attended by some 500 or so die-hard Sooner fans, a near full house packed Owen Stadium for Mildren’s debut in crimson and cream, and gasped collectively every time he launched a perfectly arcing 50-yard pass downfield. A highly anticipated sophomore season turned dismal as the team with championship aspirations struggled to a 6-4 season record. With his 1970 squad off to a sluggish 2-1 start, OU head coach Chuck Fairbanks—whose popularity had sunk so low that bumper stickers were appearing on cars and trucks urging the University to “Chuck Chuck”—installed a new option offense (at the suggestion of one of his assistant coaches, Barry Switzer, who would become most identified with the offense as OU’s wildly popular head coach from 1973 to 1988) similar to the one employed by Texas University in its national championship season the previous year. Called the “wishbone” for its V-shaped backfield formation, it became, with Mildren at the helm, a merciless rushing juggernaut. The team lost its first game with the wishbone, 41-9, to bitter rival Texas, but then went on a 5-2-1 streak that set the stage for 1971’s legendary team and season. Mildren, big, strong and fast, proved himself as gifted a rusher as he was a passer, and in the backfield with him were the durable, quick fullback Leon Crosswhite, and two-time All-American speedster Greg Pruitt. A typical play for that team would find Mildren taking a snap from center, running parallel along the line of scrimmage, then sprinting through an opening into the open field, where he frequently found Pruitt tailing him for a pitchback. Sportswriters joked that the OU radio broadcasters had to learn only one play call that season: “Mildren takes the snap, cuts upfield, he’s at the 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, pitches back to Pruitt at the 50, 45, 40, 30, 20—touchdown!” The Sooners averaged a mind boggling 472.4 yards rushing per game that season; Mildren set records for most rushing yards in a season (1,140) and season passing efficiency (209.0). Oklahoma was denied a national championship, however, by losing the so-called Game of the Century 35-31 to the Cornhuskers of Nebraska in a battle of nationally ranked #1 and #2 undefeated Big 8 teams. The Cornhuskers devised a risky, but ultimately successful, game plan that found one defender’s sole responsibility being to shadow Greg Pruitt and essentially neutralize him on offense, daring Mildren to beat them on his own. In his finest hour as a college quarterback, Mildren threw two touchdown passes and ran for two touchdowns, twice rallying his team back from double-digit deficits; but with slightly more than seven minutes remaining in the game, Nebraska put together a final, 74-yard drive that ended with tailback Jeff Kinney scoring the winning touchdown by stretching the length of his body over a pile of defenders at the line of scrimmage and breaking the plane of the goal line with the tip of the football. After the game, a weary, battered Mildren, his chinstrap typically unsnapped, searched the field for every Nebraska player he could find, shaking each one’s hand before heading to the locker room. Exuding class and humility, he remains the standard by which Oklahoma quarterbacks are measured, on the field and off. After playing three professional seasons as a defensive back for the Baltimore Colts and New England Patriots, Mildren returned to Oklahoma and entered the oil industry, then went into Democratic party politics. In 1990 he was elected Lieutenant Governor and four years later ran an unsuccessful campaign for Governor, losing to Republican Frank Keating. Recently he had served as vice chairman with Arvest Bank and co-hosted a daily talk show on an Oklahoma City all-sports radio station. Mildren is survived by his wife, Janis, three children, two brothers, and his mother, Mary.

Of the many emotional tributes to Mildren, one of the most insightful came from Oklahoma University director of athletics Joe Castiglione, who called Mildren "a legendary figure, yet his warmth and humility made him so very personable. That's what makes this loss so heartbreaking. I hope that Janis and the rest of Jack's family, all of whom are in our prayers, know that while we admired him as a great Sooner athlete, we always valued Jack so much more as a friend.

"The young people that will follow in our program would be wise to look to Jack's memory for inspiration. We will forever hold him up as an example of dedication, selflessness, achievement and the dozens of fine qualities he embodied. He is a model of what it means to be a Sooner and he will always be missed."

***

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024