Crossing Over

By David McGee

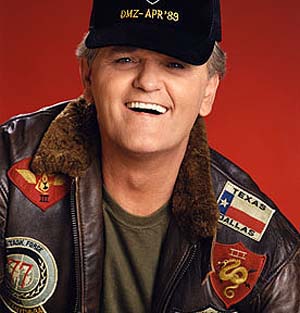

JERRY REED

Upon hearing the news of Jerry Reed's death, Brad Paisley told the God's honest truth to the Tennessean's Peter Cooper when he said, "Because he was such a great, colorful personality with his acting and song and entertaining, sometimes people didn't even notice that he was just about the best guitarist you'll ever hear."

Carl Perkins once said the same thing. Chet Atkins considered Reed a better fingerpicker than himself. A lot of other celebrated pickers confessed to being in awe of Reed's six-string artistry.

But the enduring image of Reed in most minds is of him with a wide, mischievous smile and a wicked glint in his gleaming eyes, and laughing, always laughing and upbeat, reveling being alive to the hilt. The joy he projected was reflected in his music, too. That this should be so much a part of his legacy is remarkable enough, more so considering his rugged childhood.

Born Jerry Reed Hubbard in Atlanta, GA, on March 20, 1937, to cotton mill workers Robert Spencer Hubbard and Cynthia Hubbard, Reed grew up in orphanages and foster homes after his parents divorced before he was even a year old. When he was seven he rejoined his mother after she remarried to mill worker Hubert Howard in 1944. Inspired by the fingerpicking style of Merle Travis, the fleet-fingered banjo excursions of Earl Scruggs and the "What I'd Say" rhythms of Ray Charles, Reed took up the guitar and fashioned a style born of elements of all his influences. His style was so unusual it begat its own name: "Claw Style," which he later demonstrated to good effect on an instrumental titled "The Claw." Journalist/music historian Rich Kienzle pinpointed Reed's standing in the guitarist's pantheon, writing, "If (Merle) Travis' thumb and index finger picking style was first generation, and Chet Atkins' use of thumb, index and middle finger was second, Reed's use of his entire right hand to pick (the famous 'claw' style) was the wild, untamed and dauntingly complex third generation."

The Atlanta music business legend Bill Lowery, music publisher-radio host-recording studio and label owner, was Reed's first benefactor, as his manager and booking agent, a task he assumed in 1954 after hearing the then-17-year-old artist's original composition "Aunt Meg's Wooden Leg." Lowery persuaded Capitol's Ken Nelson to give Reed a shot on the label, but their efforts over a three-year period (1955-1958), exploring a range of style in hopes of finding one that fit Reed commercially, proved fruitless. Following a short stint at Lowery's NRC label, Reed enlisted in the Army in 1959; during his service hitch he pitched a song to Brenda Lee and had his first Top 10 track with "That's All You Gotta Do," the B side of her big hit, "I'm Sorry." Signed to Columbia in 1961, he came up dry again, but he did pen his first chart topping song, this time for Porter Wagoner, 1962's "Misery Loves Company." He was also befriended by RCA's Chet Atkins, who signed Reed to the label and became a mentor to the young guitar slinger, who took to heart the lessons he learned not only from Atkins but from the other legendary Nashville producers he worked with as one of Nashville's top session guitarists in the '60s.

In a 1999 interview with this writer, Reed articulated the timeless sentiment that he made his motto after, as he would say, having it beaten into this thick skull by his producers: "Get out of the way and let it happen.

"You have in mind what you want it to sound like," Reed said. "You know these guys come off the same stump you did. If you get the pulse right, you really don't have to worry about the song. The song will play itself. Find the pulse, play the song. Listen to where the song lives, listen to what the song's about, and play that. If Chet taught me anything it's not to overplay, not to manufacture, not falsify what you're doing—just let it live. Keep it close to the melody and make music for people that don't make music. If you do that, then you're kind of fulfilling your purpose in the studio. That's what you're making music for.

"So many times when I started, I'd get in there trying to tickle all the musicians, trying to play all the licks I knew and knocking them out. Well, that didn't prove anything. But I soon had that beat out of me, by Chet, Owen Bradley and those producers who said, 'We're not in here to listen to your guitar licks. Tell you what: can you play the melody?' Jerry Kennedy used to say, 'I need a dose of ignorance here! Play some ignorance! Nobody who buys these records is gonna understand what the hell you're doing!'"

After some middling hits, he found a groove in 1967 with his song "Guitar Man," which was a hit for Reed but more famous as a cover by Elvis Presley, who made it the centerpiece of his 1968 comeback special. Reed played on the track, after receiving a call from Presley's producer, Felton Jarvis, saying Elvis wanted the guitar on his recording to sound like it sounded on Reed's version. To which Reed replied: "If you want it to sound like that, you're going have to get me in there to play guitar, because these guys (you're using in the studio) are straight pickers. I pick with my fingers and tune that guitar up all weird kind of ways.'" Elvis not only cut "Guitar Man" in the studio with Reed, but also, in the same session, his song "U.S. Male" and "Too Much Monkey Business." As his thank-you to Elvis, Reed wrote and recorded "Tupelo Mississippi Flash," and it became his first Top 20 hit.

It broke wide open for Reed in 1970 with his first million-seller, the wacky backwoods tale of "Amos Moses." Then, in 1971, came that enduring bit of real-world philosophy disguised as song, "When You're Hot, You're Hot," a five-week country chart topper and top 10 pop single to boot, followed by a Grammy Award for Best Country Performance by a Male. Good records continued to come from Reed's pen through the '70s, topped by 1977's No. 2 single, "East Bound and Down" from the film Smokey and The Bandit, featuring Reed in a co-starring role with Burt Reynolds, Sally Field and The Great One, Jackie Gleason, and thus did the picker stake out a productive career as a character actor. Cut to 1982, and there's Reed again with a two-week chart topper, "She Got the Gold Mine (I Got the Shaft)." Then, like many veteran country artists, Reed found himself supplanted on the charts and on radio by a younger generation of male artists in tight jeans and cowboy hats. So he retreated from recording, but found he still had an audience that would come out and see him perform.

In 1999 he ended a 10-year hiatus from recording by releasing an album that alternated vocal and instrumental cuts (all new Reed originals that he said "I made up out of my own sick brain") titled Pickin', recorded for his buddy Bill Lowery's Southern Tracks label. Asked by this writer what he had been doing all those years, Reed replied:

"Actually I've been doing what I've always done, except record. Only thing that's been released is things Victor put out, Best of, stuff like that, the Essential Jerry Reed. I guess when Chet quit recording me, when he left Victor, I didn't have a guitar player producing me anymore. Suddenly it was a different world. I left Victor, went over to Capitol, nothing was happening there. So I just continued touring and doing some pictures. I got away from finger picking and clawing and stuff like that. I shouldn't have done it.

"I never was a trained musician. I have some great musicians in my band and they put some of that school knowledge in my head. I went to studying the guitar neck. So while I wasn't recording it wasn't dead time. I was learning that neck a different way. I had these songs and I thought, well, heck fire, went down to Atlanta and talked to Bill Lowery, who owns Southern Tracks records, and here we are.

"But I needed time to get my chops back up. I got a band and let them do my picking, and I let my chops kinda sink into the toilet. So I had to woodshed a little bit. I got back on it, got the chops back to where I can perform a little bit. That's all I can do. I try to play other people's stuff and it sucks. I'm not a conventional guitar player; I do everything wrong. It's my way. But it's good enough for Chet, it's sure good enough for me."

1999 was a good year for Reed. Not only did Pickin' put him back on the map, but he was also featured on Old Dogs, a terrific album with his buddies Waylon Jennings, Mel Tillis and Bobby Bare, singing songs by Shel Silverstein. "Well, we were having more fun than we'd ever had with our clothes on!," he told this writer. "I mean, everybody's known everybody since dirt. I played lead guitar on Waylon's first session, and I played the intro on Bobby's 'Four Strong Winds.' I've recorded with all of them. We've known each other since Moby Dick was a minnow. Hell, I've been in it 44 years, the rest of 'em have too. You can imagine how much experience you've got in there. We didn't give a damn. I think it got on the tape that way. You know, focusing on this album's kinda automatic, because all of us are over 50! And we knew what we were gettin' into when we got in there. And the focus was just that—if we get in here and get serious, you can hang this up. You can forget this. You can't get in there and get serious about being an old man trying to do a young man's job."

For all the attention he gained, and the persona that evolved, from the riotous outing that was "When You're Hot, You're Hot," the depth of Reed's soul was expressed most profoundly on his beautiful song "A Thing Called Love," memorably covered by both Johnny Cash (who titled an album after it) and Elvis.

You can't see it with your eye

Hold it in your had

But like the wind that covers our land

Strong enough to rule the heart of any man

This thing called loveIt can lift you up

Never let you down

Take your world

And turn it all around

Ever since time

Nothing's ever been found

That's stronger than loveMost men are like me

They struggle in doubt

They trouble their minds

Day in and day out

Too busy with livin' to worry about

A little word like loveBut when I see a mother's tenderness

As she holds her young close to her breast

Then I thank God that the world's been blessed

With a thing called loveThis from a man who knew an orphan's life, but gained something important from the experience: in 1959 he married Priscilla "Prissy" Mitchell, and their union lasted to his death from emphysema on August 31, at age 71. If anyone knew about a thing called love, it was Jerry Reed. He's never been given enough credit for the tenderness in his heart.

In addition to Priscilla, he is survived by daughters Seidina Hinesley and Charlotte Elaine "Lottie" Stewart, by a grandson, Jerry Roe, and a granddaughter, Lainey Stewart.

Typical of the sort of repartee one could get into with Reed was this exchange from the 1999 interview, spurred by a query about what was happening with his acting career.

"I don't actively pursue that stuff, because I'm gonna stick to my guitar and my concerts and try to keep the band workin'," Reed said. "If pictures come along fine; if they don't, fine. I'll never be Richard Burton in the first place. If I can't be Richard Burton I don't particularly want to pursue it. No, there's nothing really happening. That don't mean it won't, because I don't know how you make a movie without me.

Obviously American cinema is hurting without you on the screen.

"And they don't even know it, do they?"

They'll come around. They'll figure it out.

"I like talking to you. You're as sick as I am."

Buy it at www.amazon.com

Charlie Walker

If you're going to have only one big hit, make it a bonafide classic. Although Charlie Walker had four top 10 singles in a recording career that began with 1956's "Only You, Only You," his signature song is his 1958 #2 (for a month) Harlan Howard-penned gem, "Pick Me Up On Your Way Down," a great single by any standard, remarkable both for its catchy arrangement and for Walker's robust vocal. It's been covered often but Walker's remains the definitive version, and justifiably so. A member of the Grand Ole Opry since 1967, Walker began his career in Dallas during the 1940s as a singer and guitarist in Bill Boyd's Cowboy Ramblers. After serving in the Army, he formed his own band, the Texas Ramblers, and began working around the Corpus Christi, TX, area. Relocating to San Antonio in 1951, he became a popular disc jockey on KMAC before starting his recording career. He also had a brief turn as an actor, appearing as Hawkshaw Hawkins in the 1985 film biography of Patsy Cline, Sweet Dreams. Recently diagnosed with colon cancer, Walker died on September 12 in Hendersonville, TN. He is survived by his wife and 10 children.

BUDDY HARMON

Legendary Nashville session drummer Buddy Harman died on August 21 at age 79; cause of death was identified as congestive heart failure. Born Murrrey Mizell Harman Jr., Buddy began his career as a session musician in 1955 and became one of the most recorded drummers in history. His credits range from Perry Como to Simon & Garfunkel to a host of country and rock 'n' roll legendary recordings, including Roger Miller's "King of the Road," Johnny Cash's "Ring of Fire," Roy Orbison's "Oh Pretty Woman," Patsy Cline's "Crazy," Loretta Lynn's "Coal Miner's Daughter," Elvis Presley's "Little Sister" and Tammy Wynette's "Stand By Your Man."

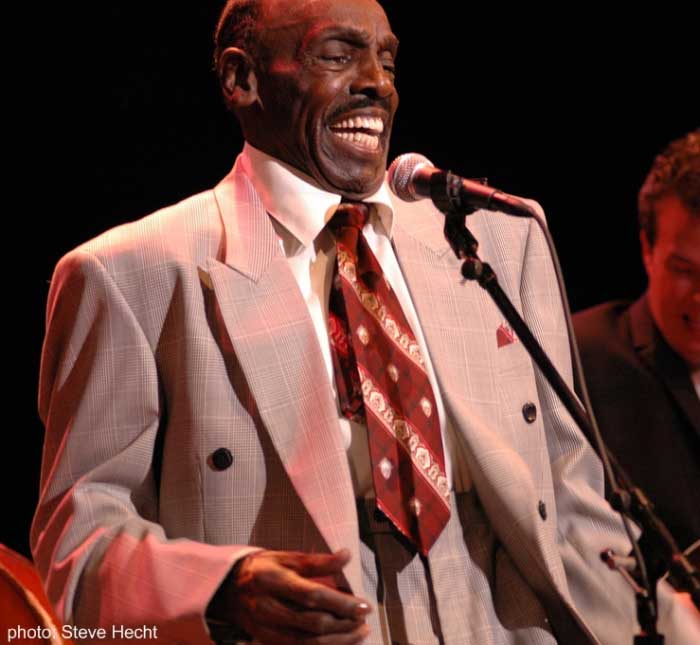

NAPPY BROWN

At press time it was learned that blues and R&B singer Nappy Brown had died of respiratory failure on September 20 in Charlotte, NC. He was 78. Born Napoleon Culp, Nappy Brown made his mark as an urban-style blues singer (with some distinctive vocal tics, such as his generous use of nonsense syllables and a style of pronunciation that could defy linguistic logic but always was entertaining) with a series of fierce singles for the Savoy label in the mid-'50s, most written by Rose Marie McCoy, one of the most prolific black writers of that era. Typical of the fate befalling most black artists of the '50s, two of Brown's best efforts, "Don't Be Angry" and "Piddily Patter Patter," received more exposure in cover versions by white artists (the Crew Cuts and Patti Page, respectively); Brown's version of "Don't Be Angry" rose to Number 25 on the pop chart before the Crew Cuts' version undercut his and went to Number 14. One of his best-known songs is far better known in its cover version by another black artist, though: "(Night Time Is) The Right Time," an R&B Top 40 hit for Brown in 1957 but a Number Five hit for Ray Charles in 1959. Brown kept working, but in the 1960s he went on the gospel circuit while holding down a variety of day jobs, including that of a circus elephant handler. In later years he sporadically popped up on record, releasing two fine albums in 1988 and 1990 in, respectively, Something Gonna Jump Out the Bushes and Tore Up.

Brown made a glorious comeback on record in 2007 with Long Time Coming on the Blind Pig label. With pride, soul and artistry intact, working with producer/guitarist Scott Cable and a tough little combo supplemented by a robust horn section, Brown served notice of being in the midst of a full-on renaissance. Whether going back to his church roots on the exultant "Take Care of Me," reprising one of his great Savoy sides ("Don't Be Angry," complete with his signature trilling "L"s, a vocal tic only Billy Stewart could emulate), teaming with his long-time blues buddy Bob Margolin on a spare, acoustic reading of Big Joe Turner and Pete Johnson's subversively salacious "Cherry Red," or wailing a powerhouse, stomping version of "Night Time," Brown demonstrated that what has been lost to age had been supplanted by a heightened sense of a song's dramatic arc. Long Time Coming was nominated for two Blues Music Awards, including best traditional blues album.

Nappy Brown's survivors include two sons, Gerard and Joseph Culp; two daughters, Maggie and Katie Culp; and seven grandchildren.

LONG TIME COMING

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024