'Mama Africa' And The Folk Music Queen: Two Voices, One Message

Miriam Makeba

March 4, 1932-November 10, 2008

Odetta

December 31, 1930-December 2, 2008

Two strong, powerful women, both born into worlds scarred by deep and pernicious segregation, both resolute in their commitment to social justice and an inclusive society, both magnificently endowed with voices capable of magnifying the power of the messages they sang, passed away a little more than a month apart near the end of 2008.

Miriam Makeba, "Mama Africa," a staunch exiled opponent of apartheid in her native South Africa, died of cardiac arrest at midnight, November 10, after performing at a concert in Naples, Italy. She was 76. Odetta, one of the leading voices of the Civil Rights Movement whose influence on succeeding generations of folk singers is incalculable, died at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City on December 2. She was 78. She had entered the hospital at the end of October for treatment for kidney failure; on December 1 the British newspaper The Guardian had reported Odetta's manager Doug Yeager as saying doctors' efforts to stabilize the singer's condition "seem to be slowly working." In a letter to fans, Yeager added: "She is sleeping a lot, but after a dialysis treatment and some food, she is coherent and talking. She is not in pain." She was hoping to recover in time to perform at President-elect Barack Obama's January 20 inauguration on January 20. "She has a big poster of Barack Obama taped on the wall across from her bed," Yeager wrote.

Miriam "Zenzi" Makeba was born in a township suburb of Johannesburg. Her father, Caswell, was Xhosa: her mother, Christina, was Swazi. The name Zenzi (from the Xhosa Uzenzile, meaning "you have no one to blame but yourself"), was a traditional name intended to provide support through life's difficulties. As a young girl she found music to be "a type of magic," she said, and poured herself into it, earning praise from instructors at the Methodist Training School in Pretoria.

Makeba broke in singing in the "mbube" vocal harmonic style that had evolved as a fusion of American jazz and ragtime combined with Anglican Church hymnody. After signing with a group called the Cuban Brothers, she got her big break in 1954 when she joined one of her country's top vocal groups, the Manhattan Brothers, whose close harmony style was similar to that of two top American group harmony favorites, the Ink Spots and the Mills Brothers. Makeba later joined the all-female Sunbeams, with whom she recorded a number of major hits. Touring around as she did, Makeba experienced firsthand the deprivations and humiliations of apartheid, which had been introduced in South Africa in 1948. Her reputation in her homeland was growing incrementally with each new tour, and the late '50s proved an especially pivotal time in bringing her message to the western world.

In 1957 she joined the African Jazz and Variety Review as a soloist and toured Africa for 18 months. Then came her casting in the female lead role in King Kong, a legendary South African musical about the life of a boxer, which played to integrated audiences and spread her reputation to the liberal white community.

The key to her international success was a small singing part in the film Come Back Africa, a dramatized documentary on black life in which Makeba played herself and sang two songs. Attending a screening of the film at the 1959 Venice film festival, she became an instant celebrity. She went to New York, where she appeared on television and played at the Village Vanguard jazz club.

Harry Belafonte became a mentor of sorts, helping her land a recording contract Stateside and steering her first solo recordings, including "Pata Pata" and "The Click Song," songs with which she became indelibly identified and continued singing throughout her career. Makeba became something of the toast of show business, hobnobbing with top celebrities such as Bing Crosby and Marlon Brando, and even appearing—less scandalously—with Marilyn Monroe at the Madison Square Garden birthday celebration for President John F. Kennedy. In the midst of her success, though, the reality of life in South Africa was never very far away. She was unable to attend her mother's funeral in 1960 because her own South African passport had been revoked. She was exiled for 30 years thereafter.

In 1963 she became more outspoken in her denunciation of apartheid, giving the first of several addresses to a UN special committee on apartheid; the South African government promptly banned her recordings. Shortly afterwards, she was the only performer to be invited by Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie to perform at the inauguration of the Organization of African Unity.

At the same time, her personal life was becoming increasingly enmeshed with her professional concerns. She was married five times, her first coming in her late teens, which produced a daughter, Bongi, born when Makeba was 17, shortly before her husband left her. A second, short-lived marriage in 1959 preceded her 1964 marriage to South African trumpeter Hugh Masekela. In 1969 she wed for a third time, to Black Panther leader Stokely Carmichael, whom she had met in Guinea a year earlier, and became involved in the radical black power agenda being advanced by the Panthers.

After Carmichael changed his name to Kwame Touré, Odetta returned with him to his own place of exile in Guinea, the west African Marxist state whose leader, Sekou Touré, gave sanctuary to enemies of the capitalist west. After that marriage ended in divorce in 1978, she turned down a proposal by the president, but two years later married an airline executive and moved to Brussels. During her time in Guinea, Makeba had become a double exile, unable to return home and, owing to her radical politics, unwelcome in many western countries (she was banned from France).

The restoration of her public image began with her appearance at London's Royal Festival Hall in 1985, her first British concert in some 11 years. She took the occasion to reply to criticism that, among other charges, she had gratuitously insulted white people, particularly some Jamaican teachers who had suffered an unjustified personal attack while watching her perform: "People have accused me of being a racist, but I am just a person for justice and humanity," she said. "People say I sing politics, but what I sing is not politics, it is the truth. I'm going to go on singing, telling the truth." In 1986 she was awarded the Dag Hammarskjöld peace prize for her campaigning efforts.

She always took time to endorse the cultural boycott of South Africa, but in 1986 she was accused of breaking the boycott by collaborating with Paul Simon on his controversial Graceland project, which included a concert in Zimbabwe the following year. Simon was the focus of the criticism for not conferring with exile groups before recruiting South African session players for the acclaimed album. But both Makeba and Masekela supported him, saying the controversy had brought important issues into general discussion and made cultural activity even more effective.

Following the release of African National Congress leader Nelson Mandela in February 1990 following a 27-year imprisonment, and the subsequent fall of apartheid, Makeba returned to South Africa after an absence of 30 years. In 2005 she announced her retirement, only to continue making repeated farewell tours up until the time of her death. "Everyone keeps calling me and saying, 'You have not come to say goodbye to us!'" she told a reporter at one of her stops.

At her final concert, she collapsed on stage after performing in memory of six immigrants from Ghana shot dead last September, an attack attributed to the city's organized crime organizations. When she was in Britain last May with an eight-piece band led by her grandson Nelson Lumumba Lee, a critic observed her to be in "confident, clear-voiced form," despite being nearly crippled by osteoarthritis. She is survived by Nelson and her granddaughter, Zenzi Monique Lee.

'She Sang Straight, No Tricks'

Born into a deeply segregated Birmingham, Alabama, society in 1930, but raised in Los Angeles, Odetta Holmes became one of the most important voices—literally—of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement and was dubbed "The Queen of American Folk Music" by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, with whom she marched at Selma; she also memorably sang "O Freedom" from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial during the 1963 March on Washington, following an introduction by Dr. King. Growing up in Los Angeles did not inure her from the injustices of bigotry, as she told New York Times reporter E. Kyle Minor in a 2000 interview. ''They didn't have signs for black and whites, but you knew where you could and couldn't go,'' she said. ''There were no signs, but there was attitude.''

Singing folk, jazz, blues, Appalachian ballads, English folk songs, spirituals and holiday songs of all cultures, she had a deep and lasting influence on the likes of Bob Dylan, Janis Joplin, Joan Baez, Mavis Staples (whose powerful guttural moans are as much a nod to Odetta's style as to the church), Joan Armtrading, and Tracy Chapman, among many notables.

In a March 1978 interview with Playboy magazine, Dylan credited Odetta with inspiring his interest in folk music. "I heard a record of hers [Odetta Sings Ballads and Blues] in a record store, back when you could listen to records right there in the store. Right then and there, I went out and traded my electric guitar and amplifier for an acoustical guitar, a flat-top Gibson. [That album was] just something vital and personal. I learned all the songs on that record. It was her first and the songs were 'Mule Skinner,' 'Waterboy,' 'Jack of Diamonds' and '(I've Been) 'Buked and (I've Been) Scorned.'"

"She was one of the great singers of late-20th-century America," folk musician and peace activist Pete Seeger told The New York Times. Seeger first met Odetta at a folk songfest in 1950. "She sang straight, no tricks. She impressed millions of people."

While working as a domestic in Los Angeles, Odetta studied music at Los Angeles City College. She received classical training in voice and began making professional appearances in musical theater as a teenager. While touring with a production of Finian's Rainbow in 1949, she discovered a burgeoning folk music scene and found another calling. "I went into folk music because it addressed more areas that we humans address than classical music does," she told writer Seth Rogovoy in a 1977 interview published in the Berkshire Eagle. "I still love classical music. It's just that it does not cover as many areas as our living mode."

She learned to play guitar and began performing in local clubs, often working across town from another aspiring folk singer, Maya Angelou. ''I was playing the Tin Angel and Maya was at the Purple Onion,'' Odetta told E. Kyle Minor of the Times. ''She's done pretty good since then.''

She began playing folk clubs on both coasts, appearing at the Blue Angel in New York and at San Francisco's hungry i and Tin Angel; teaming with Larry Mohr, she recorded her first album, Odetta and Larry, in 1954 for Fantasy Records. Her first solo recording was the 1956 album cited by Dylan, Odetta Sings Ballads and Blues.

Although primarily identified by her solo guitar-and-bass arrangements, Odetta had the musical background and intellectual curiosity to explore beyond the narrow confines of "folk" arrangements. On her 1962 album, Odetta and The Blues, she performs landmarks of '20s and '30s blues songs as originally recorded by female blues giants such as Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey, accompanied by a band comprised of jazz stalwarts Buck Clayton (trumpet), Vic Dickenson (trombone), Herb Hall (clarinet), Dick Wellstood (piano), Ahmed Abdul-Malik (bass) and "Shep" Shepherd (drums). Suitably moved by these performances, Ed Michel observes in his liner notes: "Odetta, of course, is identified primarily as a folk singer—even though she has already been heard on records with the Symphony of the Air, and her standard repertoire extends as widely through several idioms as could be desired. In addition to her own particular quality—a profoundly moving and emotionally communicative "feel"—there is in Odetta's music an unusual technical capability that lies behind the apparent ease of what she does. The skills in phrasing, the fantastic swells on notes, the overall sense of control and mastery are the sort of techniques more commonly found in Schubert Lieder, and may come as something of a surprise in a song like 'Believe I'll Go.' However, in Odetta's case, study and training is only one segment of the musical background that has gone into her development and growth into An American Musical Institution."

Making full use of her theatrical skills, Odetta continued to pursue acting in films, on television and on the stage. Her film credits include Sanctuary (1961, from the William Faulkner novel) and The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pitman (1974). In 1976 she performed in John LaMontaigne's U.S. Bicentennial opera, Be Glad Then America, playing a character named, appropriately for her, the Muse for America, in a production directed by Sarah Caldwell, then the director of the Opera Company of Boston. It was all in the usual run of events for Odetta, who told Rogovoy in the 1997 interview: "I've always acted. I'm not a prisoner singing a prison song. I'm not a child singing a children's song. I'm not a lost love singing a lost love song. I've gone into what would be, or I've acted out the song. So when I'm in a stage play or a movie or an opera, it's more of a focus on a character. Within my concerts, there are many characters that go across the stage.

"All those other things are not stretches of the imagination. The technique is there, the voice is there, the interest in acting and the ability and willingness to learn. That's not a stretch at all."

Near-silent for a 20-year period from 1977-1997 save for 1987's Movin' It On and 1988's Christmas Spirituals, Odetta wheeled back into action in 1998, both in concert and on record. A fruitful collaboration with M.C. Records, and producers Mark Carpentieri and Seth Farber yielded the Grammy nominated Blues Everywhere I Go (another tribute to the great women blues singers, a la 1962's Odetta and The Blues) in 2000; Lookin' For a Home, a well-received 2002 tribute to Lead Belly; and 2005's beautiful Gonna Let It Shine: A Concert for the Holidays, with the Holmes Brothers participating as well, a project honored with a Grammy nomination and supported with an extensive North American tour in 2006 and 2007.

On September 29, 1999, President Bill Clinton presented Odetta with the National Endowment for the Arts' National Medal of Arts. In 2004, she was honored at the Kennedy Center with the "Visionary Award" in a ceremony that included a tribute performance by Odetta acolyte Tracy Chapman. In 2005, the Library of Congress honored her with its "Living Legend Award."

In an interview with Washington Post staff writers Martin Weil and Adam Bernstein, Doug Yeager recalled Odetta's physical stamina and unquenchable will. In March 2007, Odetta, despite her physical ailments, had attended a concert in her honor in Washington. She went onstage to greet those who had attended, then astonished everyone by not only speaking to the crowd but by launching into a hearty rendition of one of her signature songs, "This Little Light of Mine."

"No one could explain it," Yeager said.

***

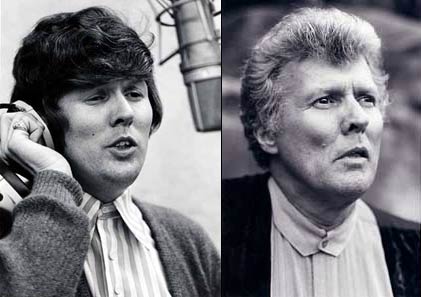

Dennis Yost

July 20, 1943-December 7, 2008

Dennis Yost: a gift for making songs uniquely hisDennis Yost, one of the finest blue-eye soul singers of the '60s and '70s as the front man for the Classics IV, died of respiratory failure at a hospital in Hamilton, Ohio, on December 7, 2008. He was 65 years old. He had been hospitalized since suffering a brain injury in a fall in 2006.

Yost's hearty, expressive baritone voice, perfectly complemented by the nuanced playing of his band and the melancholy, atmospheric arrangements crafted by producer/songwriter Buddy Buie, was the indelible signature sound on 13 consecutive chart entries, four of those being among the era's most distinctive singles (all gold, all penned in whole or in part by Buie and guitarist J.R. Cobb), beginning with "Spooky" in 1968, followed by "Stormy," the masterful heart wrencher "Traces" and the band's lone upbeat national hit, "Every Day With You Girl." Yost knew how to inhabit a song and probe it for deeper resonance, as he did most effectively on "Traces." A reflection on mementoes of lost love—"Faded photograph/covered now with lines and creases/tickets torn in half/memories in bits and pieces" went the arresting establishing lyric—"Traces" develops into a full-throated cry of the heart as Yost allows himself a fleeting few seconds of bravura belting in the chorus before returning to the subdued, winsome litanies forming the verses. ("Traces," like almost all the Classics IV's hits, was co-written by Cobb and Buie, but that duo shared the copyright on this number with a young Atlanta native, Emory Gordy, who provided arrangemens for a handful of other Classics IV number and later, as Emory Gordy Jr., accompanied some of the giants of country music, in addition to being part of Elvis Presley's TCB Band before evolving into one of Nashville's top producers, working on Steve Earle's first two studio albums and now shepherding the career of one of the great contemporary country singers of our time, Patty Loveless, his wife.) Yost could personalize a song, and sell its essential a truth, as only the best singers do. "Spooky" and "Stormy" are slight but cool tunes with seductive rhythms and genial vibes; "Traces" is a more complex proposition lyrically, and Yost inhabits it fully, expressing the narrator's simmering heartache with unresolved deep regret, putting his stamp on the emotional moment so profoundly as to make the song uniquely his forever. What didn't make it onto the radio, but what fans saw in concert and heard on non-single album tracks, was a band capable of breaking into a mean, southern soul stomp and drive—the musicians' years on the bar band circuit served them well, although that side of their artistry surfaced rarely on record and never on the charts. Even Yost, in a 2002 interview, cited the Classics IV as "the first soft-rock band."

Born in Detroit but raised in Jacksonville, FL, Yost started out with a high school band, the Echoes, as a singer/drummer—literally, he stood and sang while he drummed. When the Echoes called it quits in the mid-'60s, he joined a Top 40 cover band, Leroy and the Moments, which changed its name to the Four Classics. (Original members, apart from Yost and Cobb, included Wally Eaton on rhythm guitar, Joseph Wilson on bass—later replaced by Dean Daughtry from Roy Orbison's Candymen band—and Kim Venable on drums). Landing a record deal with Capitol, the Classics made their debut in 1966 with the Joe South-penned "Pollyanna," but ran afoul of the high flying Four Seasons, whose management objected to certain similarities between the Classics and the Seasons and mounted a successful campaign to have airplay on "Pollyanna" reduced in the New York City area. Further problems erupted when a Brooklyn group called the Classics, which had a hit single in 1963 with "Til Then," fought for right to the group name. Yost's Classics responded by becoming the Classics IV. Relocating to Atlanta, the Classics IV worked the bar band circuit (Yost was now fronting the band as lead singer, having dispensed with drumming altogether), then was signed by Imperial Records. For its first Imperial single the band cut a tune called "Spooky," originally an instrumental penned by Buddy Buie and Classics IV member J.R. Cobb that had been a regional hit for saxophonist Mike Sharpe. Buie and Cobb added lyrics to it for the Classics IV, Yost brought it home vocally, and national success followed, and continued, as "Stormy," "Traces" and "Every Day With You Girl" kept the band—now called Dennis Yost & the Classics IV—prominent on the charts.

A solid five-year run of national and regional hits ended in 1970 when band members Dean Daughtry and J.R. Cobb left to form the Atlanta Rhythm Section. Yost, though hitless thereafter, continued to tour, first with a new configuration of Classics IV (which at times actually was a sextet and did manage three charting singles between 1972-1973 when signed to the MGM-South label) and as a solo act. After moving to Nashville in 1993 he concentrated on songwriting and producing when he wasn't working the oldies circuit. According to an online biography, in recent years he had acquired exclusive rights to the trademark "The Classics IV" (the name had been sold to another group by one of the band's former managers) for both performing and recording, and had also underwent "miracle" (but unspecified) throat surgery that allowed him to sing his hits in their original keys.

Dennis Yost is survived by his wife Linda Yost, and five children.

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: [email protected]

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: [email protected]

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024