The Blues As Life's Mission

Koko Taylor, Queen Of the Blues

September 28, 1928-June 3, 2009

Koko Taylor with Alligator Records founder Bruce Iglauer

Photo by Marc NorbergKoko Taylor, the undisputed Queen of the Blues, died on June 3 at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago of complications from gastrointestinal surgery. She was 80. Taylor had rebounded from similar surgery in 2004 and returned to the active list in 2007 with one of her strongest albums ever, Old School, which earned her a record 29th Blues Music Award at ceremonies this past May in Memphis. The gala event also turned out to be her final live performance.. She won a Grammy award in 1984 for her guest appearance on Atlantic's Blues Explosion compilation album, and repeatedly won every award the blues world has to offer. In 2004, she received the NEA National Heritage Fellowship Award.

At her bedside when she passed, in addition to family and other friends, was Bruce Iglauer, who signed Taylor to his fledgling Alligator label in 1975 and remained her friend and producer thereafter. The chief Alligator spoke of her "Mississippi Delta roots" in appraising her in the Chicago Tribune. "She was of the same generation as Muddy [Waters] and [Howlin'] Wolf," he said. "Even though she had been living in Chicago since the '50s, her music was still deeply rooted in the South. She had that rhythmic sense, that sense of where you lay the words and how the band locks in around the singer, that intensity of people who have lived that life."

"Wang Dang Doodle," live, vintage Koko Taylor

Born Cora Walton in Memphis in 1928, she grew up on a sharecropper's farm outside Memphis, living in a bare bones shotgun shack bereft of electricity and running water. She and her three brothers and two sisters slept on pallets on the floor. By the time she was 11, both her parents had died and she was surviving by picking cotton. She began singing in church as a child, but found herself drawn to the blues, more by the male artists she heard on records—Sonny Boy Williamson, B.B. King, Elmore James, Howlin' Wolf—than by the blues women she admired, notably Bessie Smith and Memphis Minnie.

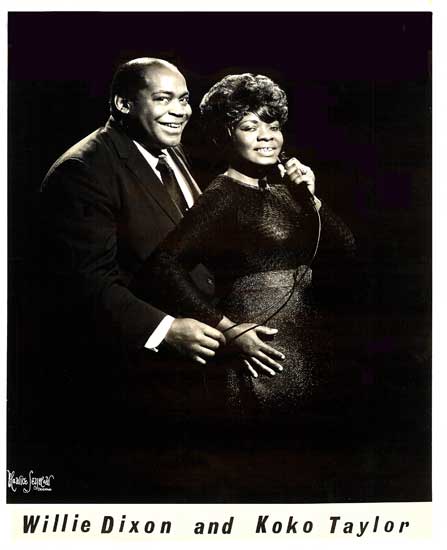

However, her blues singing began in earnest only after she relocated to Chicago in 1952, a move spurred by her desire to be with the man who would become her husband and manager, Robert "Pops" Taylor. Koko and Pops left Tennessee on the bus with only "thirty-five cents and a box of Ritz crackers" between them. She found work as a domestic in the affluent homes on the city's North Side, but began exploring her prospects as a performer on the blues circuit of Chicago's rough South and West side neighborhoods, sitting in with legends in the making such as Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf and Jimmy Reed. Working the clubs and honing her style, she kept at it for nearly 10 years, until WOPA disc jockey Big Bill Hill took Taylor to meet the resident musical genius of Chicago-based Chess Records, Willie Dixon, who had already produced and written major records for Muddy, the Wolf, Little Walter and Otis Rush. Dixon liked what heard, signed Taylor to a management and production contract, and recorded her first single, the result of an informal jam, which was released on Hill's USA label in 1963. For her first Chess single, Dixon gave Taylor one of his own compositions, an infectious shuffle titled "Wang Dang Doodle," and teamed her with some of the label's stellar musicians: Buddy Guy on guitar, Fred Below on drums, Lafayette Leake on keyboard, Jack Myers on bass, with robust sax work supplied by Donald Hawkins and arranger Gene Barge. Dixon's song was a sanitized version of an old lesbian song, "The Bull Daggers Ball" ("Fast Fuckin' Fannie" became "Fast Talkin' Fannie") and name-checked the unsavory types who showed up for the party (including Washboard Sam, who had recorded for Chess with Big Bill Broonzy). Released in 1966, "Wang Dang Doodle" caught on big time—it sold a million copies and made Taylor the brightest new star in the blues firmament. According Nadine Cohadas, author of the definitive history of the Chess label, Spinning Blues Into Gold: The Chess Brothers And The Legendary Chess Records (St. Martin's Press, 2000), Taylor never knew exactly how much money Chess made off "Wang Dang Doodle," but well understood what the single's success gave her in return: "I did not make a million dollars," she told Leonard Diamond (Leonard Chess's nephew) in a 1997 interview quoted in the book. 'I did not make fifty million, I did not make twenty-five million. But I got a hit record, and that title's been carrying me over the road all of these years."

(In a humorous corollary, Cohodas noted that Taylor's major disagreement with the Chess brothers was not over money, "but over aesthetics." She was offended by the use of a "mottled graphic" of her face on the cover of her debut album, insisting a photograph of her be used, as on other album covers. "Are you trying to kill your career?" was Leonard's immediate and non-negotiable response to this demand.)

Koko discusses Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith's influence and style, the blues in general, and the larger purpose of the self-penned song she scorches here, "Baby Please Don't Dog Me"Lighter of voice in those days, Taylor could affect a gut-rattling growl when needed and always projected a no-nonsense attitude, whether she was moaning about a mean mistreater or entreating a man to lay some good lovin' on her forthwith, as she did on her own composition, "Nitty Gritty." Taylor's sexy song was included on her first Chess album, which otherwise featured eight Dixon tunes (including "Wang Dang Doodle") among its dozen cuts. Throughout her career, Taylor remained true to the blues as she understood it, as it spoke to her. And though she was a devout woman, she stuck to advancing the life lessons the blues imparted, rather than gospel testifying. As she told writer Don Wilcock, "I know the difference from blues music and gospel music. So I don't mix the two together. They don't go together at all. That's like mixing the devil with God, and you can't do that." Which perhaps explains why she seemed to take such lubricious delight in a particular lyric from one of her sauciest Chess sides, "Twenty-Nine Ways (To My Baby's Door)," wherein she sang the classic line, "I got twenty nine ways to get to my baby's door/if he needs me bad I can find 'bout two or three more." God blushed.

The success of "Wang Dang Doodle" made her an in-demand attraction in black nightclubs throughout the South, where she toured incessantly with Jimmy Reed, but also brought her to the attention of European blues audiences, who embraced her and remained a loyal audience for the rest of her performing career. Not incidentally, she became a powerful female voice and standard bearer in a male-dominated genre, something akin to a spiritual and aesthetic godmother to the burgeoning crop of impressive young female blues artists emerging in recent years.

With Leonard Chess's sudden death in 1968 the Chess label was effectively done, and Taylor was at large again, professionally adrift. "It was a devastating time for my mom," Taylor's daughter, Joyce "Cookie" Threatt, once told the Chicago Tribune. "Then she met Bruce [Iglauer]. It was like God put him there."

During her distinguished career, Taylor recorded nine albums for Alligator, received eight Grammy nominations and made many guest appearances on various albums and tribute recordings. The charismatic blues belter appeared in the films Wild At Heart, Mercury Rising and Blues Brothers 2000, along with performances on NPR, David Letterman, Conan O'Brien, and several CBS morning news shows. On March 3, 1993 Mayor Richard M. Daley declared "Koko Taylor Day" in Chicago. In 1997, she was inducted into the Blues Foundation's Hall of Fame. The next year she was named "Chicagoan of the Year" by Chicago Magazine. In 1999, Taylor received the Blues Foundation's Lifetime Achievement Award. In 2009, she performed in Washington, D.C. at The Kennedy Center Honors program to honor Morgan Freeman.

Staying true to the hard blues with which she had made her name, Taylor also developed substantially as a balladeer (two of her most powerful performances being potent interpretations of Etta James's "I'd Rather Go Blind" and Ruth Brown's "Mama, He Treats Your Daughter Mean") and as a songwriter, while often returning to the Willie Dixon catalogue for some meat-and-potatoes fare.

After she had been laid low by her first gastrointestinal operation, she was asked by Wilcock how she found the strength to resume her career. "I had the faith and strong belief," she answered. "The faith in God, that's who brought me back." Continuing the comeback that had begun with the release of Old School, Taylor was scheduled to perform in Spain the week after her death. Iglauer remembered his friend as a woman of unflagging energy who approached her music as a mission.

"At the Blues Awards in Memphis a few weeks ago, she was absolutely glowing," Iglauer told the Chicago Tribune. "She would be exhausted standing by the edge of the stage, but when the lights went up, she would hop up and dance as soon as the music started. She would always say, 'If I can brighten one person's day with my music, that's what I live for.' "

In addition to her daughter, Koko Taylor is survived by her husband, Hays Harris; two grandchildren and three great-grandchildren. Her first husband, "Pops" Taylor, died in 1989.

From a Chess Records documentary, Koko Taylor live, performing "Wang Dang Doodle," interviews with Marshall Chess and Chuck D., offstage footage of Marshall and Koko chatting

Koko Taylor, Old School (her last album, and one of the finest of her career)

Koko Taylor, Deluxe Edition (a retrospective of the Alligator years)

Koko Taylor, What It Takes: The Chess Years (18 choice tracks from the Queen's outpourings for the Chess label, with Willie Dixon behind the board and on the bass; out of print, it's available from various Amazon sellers)

Additional reporting for this tribute was contributed by Linda Cain, founder/publisher/editor of The Chicago Blues Guide (www.chicagobluesguide.com).

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024