Show 'Nuf

Rachel Bay Jones Brings Broadway To Bluegrass On 'Showfolk'

By David McGee

Rachel Bay Jones: 'Theater was revered in my household. It was the family business; it had that feeling about it because there was such a respect for it. I think if it hadn't been for that initial insight, I might have been a scientist or a writer, a much more reclusive thing. I'm not one of those show-biz kind of people.'One of the enduring thrills for any music writer is to stumble upon an album by a virtually unknown, unheralded artist and find it to be at the very least delightful, and in its finest moments transcendent and sublime.

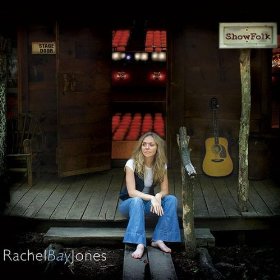

So it is with Rachel Bay Jones's debut, Showfolk, a collection of tunes originally penned for Broadway musicals that she and first-time producer David Truskinoff have recast, seamlessly, in folk, bluegrass and country styles. Jones, a veteran of the stage, will remind some of, alternately, Iris DeMent and Pam Tillis, but how she finds her way into these songs through down-home routes is all her own. Her veteran Broadway partner, producer David Truskinoff (working with co-producer Daniel A. Weiss), who is most accustomed to working with orchestras, currently as the musical director for Rent's touring company (as he was for the must-see musical's final two years on the Great White Way), makes a smooth transition to acoustic roots music, crafting empathetic small combo arrangements designed to both underscore the dramatic arc of the songs' narratives and provide Jones with an evocative backdrop for her varied, infectious stylings. For the listener, the end result is a mesmerizing, unforgettable experience

Commenting on the thin line separating certain musical styles is practically a second calling for many musicians and music writers, but it may take Showfolk to remind everyone about the close relationship between Broadway, country and bluegrass. But consider: Showfolk spotlights songs about love and yearning (in, for instance, Jones's exquisitely tender reading of "Little Bird, Little Bird," from Man of La Mancha, here recast in a delicate arrangement with mandolin, guitar, bass, accordion, dobro, and Randy Redd supplying a sensitive second vocal to the plaintive, heart tugging lead); exultant first feelings of new love (a loping, backwoods take on "Lucky To Be Me," from Leonard Bernstein's On the Town, with music and lyrics by Adolph Green and Betty Comden—the Broadway version, not the mutilated film adaptation-rich in banjo and fiddle and a vocal by Jones that strikes an affecting balance between the "thunderstruck" girl of the lyrics and the near-giddiness you can hear burbling right below the surface of her all-smiles vocal); a character study, rich in detail, atmosphere and humanity, in the Irish-tinged, fiddle-rich ballad "Streets of Dublin," from A Man Of No Importance; a reflective look back at a lost love affectionately remembered for what it gave the singer while it lasted, "For Good," from the Stephen Schwartz musical, Wicked, treated in sober terms with an acoustic guitar and dobro adding bluesy, emotional fills in the spaces between Jones's hushed, piercing memories; a surging, dark, keening treatise on a woman living a double life, including that of a prostitute, and ostracized by her hometown folks in "Wicked Little Town" from the rock musical Hedwig and The Angry Inch; the search for true love in one of the most exuberant and joyous moments on record in recent years, "Where, Oh Where (Is My Baby Darlin')," a raucous, foot stomping workout from The Robber Bridegroom (a Broadway hit in 1976 that featured, among its cast members, Tony Trischka, well before he became a bluegrass icon, but right at home in this reinterpretation of a Grimm brothers tale set in the South with a bluegrass-inspired libretto by Robert Waldman and Alfred Uhry) that is remarkable for the stimulating synergy between fiddler Sam Bardfeld and multi-instrumentalist Bobby Baxmeyer on banjo, mandolin and acoustic guitar behind an electrifying duet set-to between Jones and Redd—the precision timing of their exits, entrances and harmonizing is in and of itself the album's most exhilarating moment, truly wondrous in its passionate urgency—upping the energy ante from their bucolic pairing earlier on "Little Bird, Little Bird".

Stories all, are these, but mere chapters in a larger tale about the way we live. In this sense, and in the sure hands of Jones, Truskinoff and their supporting musicians—and Truskinoff is adamant about emphasizing the collaborative nature of Showfolk ("I absolutely could not have done it without the talent of every single person that was on it. That's really how I like to work. I enjoy the collaboration; I crave collaboration.")—the songwriters represented on this album are working the same turf as Bill Monroe, the Louvin Brothers, Roger Miller, Harlan Howard, Johnny Cash, Rosanne Cash, Rodney Crowell, Rhonda Vincent, exploring the human condition in poetic evocations of the heart's deepest longings and humankind's unpredictable responses to bumps in the road. Jones, who has spent her entire career in the theater but has some background as a bluegrass singer, albeit not professionally, saw the connection immediately once she and Truskinoff began wading through theater songs to adapt to country and bluegrass styles.

Producer David Truskinoff and Rachel Bay Jones: 'Certain artists,' Truskinoff says, 'whether they're playing an instrument or singing their instrument, have a way of truly revealing a part of themselves in their instrument, more than just technique or choices. It actually comes out in a way you can't quite put your finger on, but you know you're hearing a part of this person's soul. Rachel has that ability.' Of Truskinoff, Jones says: 'David comes to everything from a very poetic center and he's able to find the simple poetry in everything.'"In theater music, there's so many great stories; everything has a reason," she explains. "When a song is produced for the theater, it has to propel the action. In order for it to be a successful song in the theater it can't just be, 'Oh, I'm blue, I'm sitting around and I'm blue,' it has movement and all that. We found, when we were going through this, that the things we were drawn to obviously had a structure that would fit with what we were trying to do in rearranging it, but the lyrics tended to have a natural element where they dealt with things—when you stripped them of their original arrangement, they had the roots we were looking for."

"When we first even talked about the concept, we kept having such wonderful conversations and giggling to ourselves that this is kind of amazing because there are such similarities between the two types of music," Truskinoff adds. "The storytelling nature of theater songs and folk songs is one similarity; we wanted most of all to keep it about the storytelling, and Rachel does that so well. So the musical language we used was almost a separate conversation, and that's where we would go in with Bobby Baxmeyer and play with different instruments and decide the tonal sound we wanted to have. But as far as the concept of the songs, we were surprised they were fitting so well. And it tickled us to know, some people will never have heard these theater songs and say, 'Wow, that's a damn good song! I never thought I would enjoy listening to a theater song.'"

The mystery and magic of Showfolk remain singular—Jones and Truskinoff have crafted something new, sui generis, here, but they're not theater folk slumming. For Truskinoff, Showfolk represents the start of new career phase as a producer, something he's been aiming for, as well as the launch of his own label, Plum Song Records. For Jones, it's a bit of a coming-full-circle moment in a fruitful career as a stage actor and singer.

Born in New York, raised in both Hollywood and Boca Raton, Florida, by parents who were actors and revered the theater, she took to the boards professionally at age 12, performing in regional theater in south Florida and garnering favorable local reviews from the git-go. Her breakout role, by her own admission, came in her late teens, in Jacques Brel Is Alive and Well And Living In Paris, which immediately preceded a precipitous move to New York to pursue larger ambitions. College was not in the picture—only theater, which she describes as "the family business.

"I've always loved the theater and it was revered in my household," she says in a speaking voice remarkably as soft and tender as her singing voice. "It was the family business; it had that feeling about it because there was such a respect for the theater. If it hadn't been for that initial insight, I might have been a scientist or a writer, a much more reclusive thing. I'm not one of those show-biz kind of people. But I love it—I love communicating with an audience, and I think that's something that's kept me in the theater for as long as I've been in it."

'There's such honesty and purity in this music. It's always joyful, even if you're singing about murdering down by the river, it seems like there's still this happy, plunky banjo going. There's something about it that expresses such exuberance and life.'But inside this thespian heart also beat the heart of a country girl. In the solitude of her own home she never listened to theater music—it was always bluegrass and folk. So much as she had up and moved to New York way back when, so did she up and move back south in the mid-'90s, not to Florida, but to Flat Rock and Asheville, North Carolina, where she completely immersed herself in a thriving bluegrass scene; for awhile she was in a band called American Standard, which peaked when it opened a show for Roger McGuinn. Even as the theater always beckons, roots music exerts a similar pull on her. Something about its ties to home and hearth, to specific locales, is meaningful to one who has a peripatetic history.

"There's such honesty and purity in this music," she says. "It's always joyful, even if you're singing about murdering down by the river, it seems like there's still this happy, plunky banjo going; I don't know, there's something about it that expresses such exuberance and life. I think also the history of it really gets me. How long it's been around, where it came from, how tied it is to a place, to America and to the mountains when I was there."

She also had occasion to experience bluegrass at its true grass roots level when she met the Waller brothers, Doug and Jack, a pair of old-timers who took Jones and her singing partner under their wings. Jones: "When I met them I was singing with a girlfriend of mine and they invited us out to their cabin in the mountains, which was a ramshackle Appalachian cabin—they had an outhouse still. They had just got running water, and their spinster sister took care of them, Doug was 90 and his younger brother Jack was 85. Being in that environment, singing old-timey Appalachian ballads, that was their big thing."

This immersion in ground-zero bluegrass remains with Jones, as vibrant and vital to her sense of self as is the theater. Still, she had no plans to record a Showfolk-style album, despite persistent appeals to do so by a director friend, Abe Reybold, who earns an "Original concept by" credit on the album sleeve. Jones says Reybold proposed the concept as long ago as 15 years back, because he could hear the country in Jones's voice and knew well of her love for the theater. But it didn't come together until she and Truskinoff, with whom she had worked on a regional theater project in Florida, that the idea gained momentum. For Jones the stars were aligned in way they had not been a decade and a half earlier when Reybold first articulated his epiphany; for Truskinoff, the timing could hardly have been better to begin pursuing his grander ambitions.

A graduate of the University of Cincinnati/College Conservatory of Music who has served on the faculties of the Yale School of Drama, the National Theatre Institute and the American Musical and Dramatic Academy, Truskinoff has an extensive theater resume, especially when it comes to Rent: in addition to his Broadway and touring company responsibilities as musical director, he also conducted the premier German (Berlin) and French (Montreal) productions, as well as the 10th anniversary Asian tour.

"My history has always been very varied, I've gone down different roads and I really enjoy that," Truskinoff says. "Sometimes it's a little scary because you're not quite sure what's around the bend. But on the other hand, it's very exciting. I've been connected with Rent and doing musical conducting for a long time; this seemed like a good opportunity-I wanted to start something on my own and I love the whole nature of creating in this way. I've also written and arranged, but this way of actually producing and building from the ground up, driving and directing a real idea, seemed so exciting to me."

There was a time when Broadway songs became hit pop songs, embraced by mainstream America and given a showcase on such top-rated variety shows as The Ed Sullivan Show. That time has long passed, but on Showfolk, Jones and Truskinoff roamed far and wide for material rather than settle for songs pulled from the best-known Broadway hits. The stirring "Streets of Dublin," for example, one of Jones's most dramatic performances on the disc, originated with A Man of No Importance, a short-lived play (opened September 2002, closed December 2002) based on a film starring Albert Finney and boasting a book by Terrence McNally; wistful and melancholic, "Stars And the Moon" emanates from the Jason Robert Brown show Songs For a New World, which ran only 28 performances off-Broadway in 1995. In fact, the only song among the chosen 11 that would be instantly familiar to most listeners is the Lesley Bricusse-Anthony Newley self-affirming warhorse, "Gonna Build Me a Mountain," from the duo's 1962 Broadway hit, Stop The World-I Want To Get Off, which Jones and Truskinoff enhance by downplaying the traditional anthemic-like approach and instead going for an introspective gospel feel.

The principals confirm their focus was on less familiar material, but other factors were more critical, both from commercial and aesthetic standpoints.

"We were always walking the line because, obviously, David wants to sell records," says Jones. "So he wanted to try to get some of the big shows in there, or at least shows people would recognize. We didn't want the whole thing to be one commercial success after another. I think ultimately what drove us is that we wanted to sing the songs we wanted to sing. We wanted to make the album we wanted to make. If we needed a certain kind of song to go in this slot, and it could come from Wicked, so much the better. If we loved it, that was great. So that was a consideration, but it was a small consideration. What we hoped then, and what's starting to happen, it seems, is that it would start out as a record that got appreciated by people inside the industry, people who already were theater lovers and would pick up on something like this, and then slowly, virally, it would spread on its own."

"We definitely wanted to be accessible," Truskinoff confirms. "The song from Robber Bridegroom is actually the one song we really didn't change all that much as far as the genre. We just wanted to go a tad more authentically with it. I was so thrilled when we sent to Robert Waldman and Alfred Uhry, who wrote the show. They were so thrilled with it, and so tickled by it, not because it was a nice rendition of the song but because we took it a step further into its roots. Yeah, we wanted to be accessible but also to present some older, more obscure things. It was very important to us to do some newer stuff also, like the song from Rent ["Another Day," a kind of hopeful benediction at album's close and not chosen, Truskinoff insists, because it was from Rent, in which he obviously has a vested interest] and the song from Wicked."

In the end, the mutual admiration society between Jones and Truskinoff was enhanced by the experience of Showfolk. She credits him with keeping everyone honest musically and on course conceptually; he marvels at the truth and vulnerability in her artistry.

"David has a real talent for cutting through the BS," Jones says. "He can see the heart at the center of things. He comes to everything from a very poetic center and he's able to find the simple poetry in everything. He's also a lovely pianist and accompanist and conductor, and he goes for truth. David goes for truth. Anything that's not true, not honest, not real, it falls away immediately as soon as he puts his hand to it. I think that's his greatest gift. He trusts me, so a lot of what he did was supportive, not heavy handed."

To Truskinoff, Jones has "that thing. I hearing someone who's just heard her sing say, 'She just has this thing. I don't know what it is, but there's something going on there.' There's something special and it doesn't happen all the time. Certain artists, whether they're playing an instrument or singing their instrument, have a way of truly revealing a part of themselves in their instrument, more than just technique or choices. It actually comes out in a way you can't quite put your finger on, but you know you're hearing a part of this person's soul. I think she has that ability. I can't really describe it any more than that, because I don't know what it is. But I know, when I hear her sing, there is something unspoken there that's really very special. I love Eric Clapton as a guitarist, and somehow when he plays I feel like I'm hearing something in that man's soul that another person playing the same notes and even the same style on the same guitar you're just not gonna get. I think Rachel has that ability."

The best news of all, short of Showfolk gaining traction commercially, is the prospect for another volume. No shortage of material out there, but...

"Choosing the material for this album was excruciating," Jones admits. "We had to discard so many songs because they wouldn't fit, so there's definitely another album or two of material that we want to explore. There's a sound we love, the band we assembled we love and want to keep doing it. I don't know if it would be theater music or what we would do, but I think it's a sound that will continue."

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: [email protected]

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: [email protected]

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024