Crossing Over

Wayne Allwine

Feb. 7, 1947-Feb. 2. 2009

Voice of Mickey Mouse was married to the voice of Minnie Mouse

(photo courtesy Frank Anzalone photography)

Wayne Allwine, a Walt Disney Studios voice-over artist who was the voice of Mickey Mouse for more than three decades, died in Los Angeles on Feb. 2. He was 62. Allwine was only the third person to voice the Mickey Mouse character, following the original voice, Walt Disney, who in 1947 turned the job over to Jimmy Macdonald, who did the honors until Allwine took over in 1976. Mickey made his debut in the 1928 cartoon short, "Steamboat Willie."

Allwine, an Emmy Award-winning former sound effects editor and foley artist, died of complications of diabetes, according to his voice-over artist wife, Russi Taylor, who was the voice of Minnie Mouse.

"Wayne was my hero," Taylor, who began voicing Minnie in 1986, told The Los Angels Times. "He really loved doing Mickey Mouse and was very proud that he did it 32 years."

Among Allwine's credits as the voice of Disney's top animated star: Mickey's Christmas Carol (1983), The Prince and the Pauper (1990) and Mickey, Donald, Goofy: The Three Musketeers (2004) and TV series Mickey MouseWorks, House of Mouse and Mickey Mouse Clubhouse.

In a statement issued by the Walt Disney Co., Chief Executive Robert A. Iger described a "profound sense of loss and sadness throughout our company" over Allwine's passing, adding: "Wayne's great talent, deep compassion, kindness and gentle way, all of which shone brightly through his alter ego, will be greatly missed."

Mickey's Christmas Carol, Part 1

voice of Mickey by Wayne Allwine, RIP

Mickey's Christmas Carol, Part 2

Mickey's Christmas Carol, Part 3***

Joan A. Stanton

April 16, 1915-May 21, 2009

Actress and radio voice of Lois Lane

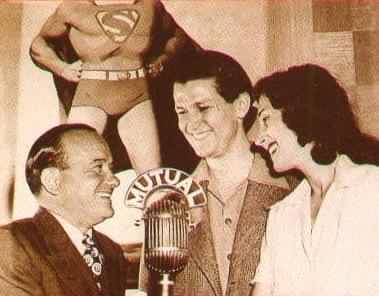

Superman on the radio: At right, Joan Alexander (Joan A. Stanton) as Lois Lane, Bud Collyer (center) as Superman and announcer Jason Beck (left) send the adventures of the Man of Steel out over the airwaves and into the craw of the KKK.Joan A. Stanton, better known as Joan Alexander in the 1940s when she was the voice of Lois Lane in the Superman radio series, died of an intestinal blockage on May 21 in Manhattan. She was 94. Described by Bruce Weber in a New York Times obituary as "a dark-haired beauty, model and stage actress," Alexander was one of the busiest radio actresses of her day. She originated the role of the loyal secretary Della Street on the radio version of Perry Mason, but Lois was by far her most famous role. Stanton later reprised her role as the voice of Lois Lane in the 1966 animated series The New Adventures of Superman. The original Superman radio series launched in 1940, two after the titular character's introduction in Action Comics. The Lois Lane character made her debut in the seventh episode on radio. Various sources indicate Alexander was not the original Lois Lane, but she joined the cast early in the show's run and appeared in hundreds of episodes, effectively claiming the role of the radio Lois as her own.

She was born Louise Abrass in St. Paul, Minnesota, on April 16, 1915, but when she was young, her father died, her mother remarried, and her stepfather moved the family to Brooklyn, where she was raised. Her stage name is derived from her love for actress Joan Crawford, but the origin of her surname is unknown, even to her daughter, the novelist Jane Stanton Hitchcock. She was married at one time to actor John Sylvester White, who later played Mr. Woodman on the popular '70s sitcom Welcome Back, Kotter.

Last year Alexander filed suit against her financial adviser Kenneth Ira Starr, accusing him of losing and stealing millions of dollars of her money. Alexander's late husband, businessman Arthur Stanton, left her $70 million when he died in 1987.

In addition to her daughter, who lives in New York and Washington, Stanton is survived by a son, Tim, of Manhattan, and a grandson, Liam.

Though it is little noted nor long remembered today, the Superman radio program tackled bigger issues than was common for radio fare in its day and thus paved the way for other socially conscious programming. Racial and religious intolerance were the driving narrative lines of a series of shows under the theme "Unity House." Apparently, too, the show baited the KKK repeatedly by broadcasting certain of the hate organization's code words, forcing an apoplectic Grand Dragon to tune in, at the ready to change the password if Superman revealed it on the air. Attempts by the KKK to intimidate Kellog's, the show's sponsor, with a threatened boycott of its products failed.

The supermansupersite.com provides a succinct summation of the show's achievement:

The Adventures of Superman radio series catapulted into the media spotlight with its "Unity House" story line in 1946. "Recently the Superman program underwent a change as drastic and unprecedented as some of its hero's exploits," wrote columnist Harriet Van Horne, "It became a program with a message." After years of battling mad scientists, atomic weapons and supernatural menaces, Superman took up the battle against racial and religious intolerance when a rabbi and a Catholic priest were menaced by young vigilantes out to destroy an interfaith community house. In the final installment, Superman tells the gang members, "Remember this as long as you live: Whenever you meet up with anyone who is trying to cause trouble between people-anyone who tries to tell you that a man can't be a good citizen because of his religious beliefs-you can be sure that troublemaker is a rotten citzen himself and an inhuman being. Don't ever forget that!""Superman is the first children's program to develop a social consciousness," reported Newsweek "To do it, Superman, Inc., the company that controls the Man of Tomorrow in all media, had to sell the idea to the Kellogg. Co. sposoners, and Mutual—two perpetual worriers over the response of reactionary listeners." Officials for both sponsor and network were relieved when the show's plea for tolerance began attracting the highest ratings in the history of the series. "Superman's Hooper rating has risen perceptibly since the change in plot." reported the New York World Tribune on 4 June 1946. "The show is now Number One." The story line attracted endorsements from dozens of organizations including the National Conference on Christians and Jews, the American Newspaper Guild, the American Veteran's Committee, the United Parents Association, the Associated Negro Press and the Boys Clubs of America. After years of protecting his dual identity, Bud Collyer finally stepped into the media spotlight to proudly promote the "Unity House" story line.

Superman also caused a considerable amount of bad feeling among the Ku Klux Klan by mentioning various KKK code words on the program. The code words had been passed on to Superman via the Anti-Defamation League. As a result, Samuel Green, Grand Dragon of the KKK, had to spend part of his afternoon with his ear pressed against the radio. As soon as Superman used a real KKK password, Green sent out urgent orders for a new one. The Grand Dragon is said to have taken this very badly and to have vented his spite on Kellog's Pep by attempting to stop local sales of the cereal. The Kellogg people refused to be intimidated.

The success of the "Unity House" series led to follow-up story lines on juvenile delinquency and school absenteeism. It was the finest moment in the history of radio's greatest adventure program.

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024