'I've been doing this, somebody listen to me.'

Is there any better time for Christine Santelli?

By David McGee

Photos by Alicia Zappier

"I've had several tattoos and piercings, but I never want to get stapled again."

Well, in journalism that's called a "grabber" lead.

The set at the Dubliner pub in Hoboken has barely begun and Christine Santelli is explaining to an attentive, fairly packed house how she happened to wind up with a staple in one of her fingers only minutes before she took the stage. It was an accident behind the bar, where was actually taking orders and serving drinks prior to her performance. This is not an unusual occurrence. Santellli, who books the music at the Dubliner, seems to have the run of the place and a command of the room even before she starts playing. It feels very much like her party. She has a way about her. And piercing Dietrich eyes that will look through you and melt your heart all at once. You don't need to know she has a Master's degree in Education to sense she is the smartest person in the room. Maybe the most complex too, working a tender-tough persona with an adroit sense of balance between the two and never really letting on which side of her she feels most comfortable with—not even in her exquisitely crafted, literate lyrics, which further the Santelli dialectic: Is she the brooding, doom-laden protagonist of "Good Day For a Hangin'," seeing a world of hurt with every step she takes, or the open-hearted, yearning romantic of the beautiful, gently rocking plea, "Butterfly," not seeking big, sweeping gestures of commitment but rather a kiss on the hand, a smile "as you drive away," a phone call "in the afternoon," a tender caress of her face?

"Have you ever seen Christine play before?" asks bartender/musician Mike Frensley. "She's the real deal." He nods. "The real deal."

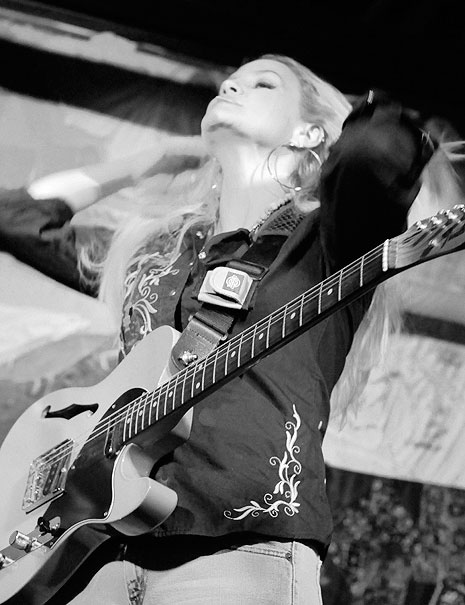

Nothing in her Dubliner performance (she plays there every third Tuesday but can also be found sitting in on open mike and singer-songwriter nights throughout each month) or during two sets—one solo acoustic, one with her first-rate band—later in the week in Manhattan before ungracious audiences at Hill Country Barbecue confirmed the veracity of Frensley's assessment. She may be the real deal in a way few artists who have laid claim to that honorific could justify it. It doesn't hurt that she looks great with the Levi's, western shirts, long, flowing blonde hair and those Dietrich eyes. But her original songs set her apart, way apart, from most of her peers. Nominally a blues artist, she's equally at home and equally persuasive in folk and country. She writes what she feels, not "a blues song," or "a country song." She writes songs, period. That she is so stylistically diverse makes it hard to pigeonhole her, possibly to the detriment of her commercial advancement but to the distinct advantage of her deeply emotional art.

Before the Dubliner set, two 20-something young women were positively giggly over the prospect of hearing "Butterfly" live. They heard a touching rendition of their favorite song. But both the Dubliner and Hill Country audiences also heard her grind out tough blues in "Ode to Bill," snarling blues in "Guilty," a gently fingerpicked and delicately sung version of Elizabeth Cotton's "Freight Train," the semi-autobiographical tragedy that unfolds with a country lope but devastating finality (and a gorgeous refain) in "She Wasn't Wrong," and the Spanish flavored romance of "In the Distance." Her rhythm section of bassist Tim Tindall and drummer (who doubles as her husband) Matt Mousseau played this eclectic mix with impressive subtlety to the shifting emotional textures Santelli shapes during a set, and electric guitarist Jason Green pretty much blew everyone away with a florid but self-effacing display of chops, spitting out howling blues choruses, B.B. King-ish single string runs, rich, jump blues chordings, and some jazzy interludes against the anxious rhythm of "Justify." Santelli brought it all back home, though, with her remarkable singing, inhabiting each song fully, and using both the rough, husky, Janis Joplin-like edges and gently caressing balladeer's timbres of her voice to bring her lyrics alive, underscoring the dramatic shifts in character she reveals in literary flourishes in, say, "She Wasn't Wrong," when your perception of the song's wandering minstrel is irrevocably altered when, in the second verse, she sings, "months went by for this child/made her harder than stone/fall and winter were mild/spring came in like a storm." Child? Child? That's more than a convenient rhyme with "mild"-it completely alters our understanding of the character in question and foreshadows her ultimate demise. Santelli's songs are full of such sly turnarounds designed to lay you low and make sure you never forget her.

But you do have to listen. In her opening acoustic set at Hill Country, playing upstairs near the bar area to maybe half a dozen people, with a dining room only yards away, full and oblivious to her presence, she offered an assured, spirited set and sang with undiminished conviction, no matter the din. (When your audience is busy chowing down on ribs the size of a small heifer, it is otherwise occupied.) A pro's pro, she refused to give in and made the moment hers. At the end, after announcing her band set coming up downstairs, she said, oh so sweetly, oh so acidly, "Thank you for listening. You're one of the best audiences I've ever played for." Making of that, too, her moment.

***

Though she's a Jersey girl now, living in Jersey City, about three-quarters of a mile from the Dubliner in Hoboken, Christine Santelli hails from upstate New York, specifically the Albany suburb of Clifton Park. Neither her birth parents nor her adoptive parents were musical, apart from her adoptive mother playing a bit of piano. She took piano lessons as a child, "but I didn't want to," from age seven until she was 15. When she was eight, she attended a family reunion and met some older cousins, who spent part of the day sitting around a campfire singing, and playing guitar.

"I begged my parents, 'That's what I want to do. I want to play guitar.' So they bought a cheap Ventura guitar and told me I had to take lessons with my brother, because they weren't sure I really wanted to do this. Eventually I started taking lessons by myself, when I was eight years old."

Along with acquiring a guitar, Santelli found out she had a singing voice too. She played in talent shows and began performing publicly when she was 15. Between the budding eight-year-old guitarist and the bold performer of 15, something happened: when she was 12 she heard the blues and saw a path.

"Bessie Smith was like the first thing I ever listened to. Then I got into Etta James, I loved her voice, Koko Taylor, Brownie McGhee, John Lee Hooker."

Then, "Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, Leonard Cohen"—which maybe explains some of the delicious Cohen-style ambiguity and exotic ambiance of songs such as the cabaret-style "Better To Me" off her towering Tales From the Red Room album—and hence the songwriter emerged.

"So I started out doing folk kind of stuff, then I went into electric blues in college, then found my way back to the acoustic songwriting later on."

After high school she entered the State University of New York at Plattsburgh, where she earned a degree in psychology and the aforementioned Master's in Education. While a student at Plattsburgh she was also playing in various blues bands, formed her own group, Christine & the Dickens, and came to a fork in the road.

"I went to college to please my parents," she says, "but after I got my Masters and was offered a job, I said, 'You know what? This is not what I want to do.' I took my band from upstate New York and moved them down to New York City. Been down here ever since. This is all I ever wanted to do."

That 1993 move to New York is in part captured in the vivid opening lines of "She Wasn't Wrong" (which is in a nutshell how she feels about her decision to choose the path of most resistance following graduation)—"It was a long drive down to the city/money wouldn't last too long/she was a woman who thought she was pretty/she took a job where she didn't belong/never lost sight of a dream/she played guitar/and she'd sing/never thought it'd take so long/she stuck it out/she wasn't wrong..."-which she says are rooted in personal experience but then veer off into imaginative art.

"It started as a song based on personal experience, as most songs do and then it turns into something else. The first line, 'It was a long drive down to the city,' that first day coming down here, there's probably a million songs I could have written from that day, from the van blowing up to the bass player getting thrown in jail on the way down here to waking my parents up on the way home to drop something off at two o'clock in the morning to getting to my apartment at five a.m. and the realtor waiting in the parking lot for me. But it started on that journey coming down here."

Christine & the Dickens evolved into simply the Christine Santelli Band, which made its debut on 24 Hours, an album of original Santelli material released in 1993. The one constant from the original band, and in Santelli's life for the past 21 years, is drummer Matt Mousseau, the first drummer she ever played with and now her husband of a decade's standing. There the line of Santelli's career gets interesting because it shows an aggressiveness in getting her music out to the world that is striking, considering how hard such a thing was in those pre-MySpace/Facebook/digital download days. She gained a foothold in Europe, and her next two album were live collections—Live in Paris, Live in Moscow—of cover songs, before she returned with a new batch of originals in 2002, Season Of a Child, produced by Popa Chubby and coming in the wake of her being voted "Blues Artist of the Year Deserving of Wider Recognition)" in Downbeat's 46th annual critic's poll.

"I felt much more accepted overseas than over here," she says. "As far as being in the New York City area, in the blues community, I definitely made my mark there, but outside of New York, in the States, not so much. It was much easier to book tours and be much more appreciated and make money over in Europe. We played a lot of cities in Switzerland, I played the Montreux Jazz Festival a couple of years back, did a couple of shows there. We played in South Africa, in Johannesburg, did a lot of different cities in Norway."

Her thoughts on why she's had so much success in other countries?

"Huh." She pauses, as if the question has never cropped up before.

"Because they like good music?" She laughs—or rather cackles, in a Joplin-esque way, for those who remember-at her own proposition. "They love American music—not current American music—well, I'm sure some of them do. It's amazing how many people turn out for shows compared to here."

Essentially, however, Christine Santelli, though now being signed to Vizztone and having a label with real infrastructure working her album instead of doing everything herself, is still clawing at the next rung up the ladder. She books her own shows, the upshot being that outside of Europe, most of her shows in America are either in New York (state and City) or New Jersey. MySpace is not the boon for blues artists that it's been for pop, rock and hip-hop/rap artists. The life is a grind.

"It's hard, and it's hard to get anywhere," Santelli admits, matter of factly rather than with any bitterness or self-pity. "I've been very fortunate in the places I've been able to go and book shows, festivals and that. But it's tough; it's really tough. Like the Dubliner, where Gina [Sicilia, her labelmate and friend, who hipped the fellows at Vizztone to her] and I are playing, I run the music over there, so I also do that to try to keep musicians together and have a place to come home to when they're not touring. I've been booking in that music community for the last 17 years It's tough, because I write, I book my own shows, I try to promote myself and then I also do this other thing too. It's nice to have the help Vizztone provides."

Artists evolve at their own pace, not according to anyone's calendar or release schedule. Santelli's earlier studio albums all have bursts of inspired, elevated artistry, and the live albums prove how genuine and personable a performer she is, not to mention showing off her nice touch in putting her own stamp on other writers' songs without undermining the essence of the originals. But 2006's Tales From the Red Room, and the new Any Better Time, are on a whole other level, conceptually rich and varied, but whole, seamless, transcendent songwriting, singing and playing (a nod is due here to Dave Gross, who produced both albums with an unerring touch and infallible instincts for the nuances of Santelli's music). On Any Better Time, Santelli stays on the path of Tales From the Red Room, which features a handful of powerful country originals among its blues, most notably the aforementioned gem, "She Wasn't Wrong," with Mazz Swift adding an unforgettable lonesome fiddle line to support Santelli's tense and terse tale of a gal who followed her dream to destruction, and "Take a Look," a thoughtful, bucolic road song with the topical theme of learning to appreciate the world's natural wonders in lieu of partaking of a tour bus's mundane chatter. On Any Better Time she offers "Ponytails," a lilting, country-flavored ballad spiced with an evocative accordion line; "Down In the Valley," a yearning, country-tinged tale of spouses physically separated by death but spiritually ever-present in each other's hearts; "Calgary," a beautiful, finger-picked and fiddle-flecked reminiscence of lost love, as tender and heart-tugging as Ian Tyson at most plaintive (with that title, perhaps it's an homage to Tyson, in fact); the moody "Lily's Song," concerning a young lady who needs a boost in self confidence to fully flower, featuring a dry, dusty vocal by Santelli backed by Gibb Wharton's evocative, moaning pedal steel lines and some frisky Rhodes interjections by Brian Mitchell that blur the song's point of origin stylistically but make perfect sense; and an album closer that leaves no doubt as to its latitudes and longitudes, being "On the Farm," an unabashed country hoedown with a playful lyric about country cookin', rousing, foot-stomping acoustic guitar and banjo sparring, jubilant handclaps and an altogether festive front-porch atmosphere about it.

Santelli breaks the blues mold stylistically from time to time while never leaving the blues behind—the carny atmosphere of "For You" gives the song a shambling, Tom Waits-like quality (especially the calliope and the squeeze toys), and indeed the lyrics are more stream of consciousness images ("a carnival a party clown/to spend the day without a sound/a foreign land and a shooting star/a firefly lighting up a jar for you") than a structured narrative; "Butterfly" is a distinct evocation of a particular sound and style—in this case, a '60s pop-rock ballad, with a driving rhythm, a rich organ backdrop, warm sonic textures, and a sunny, upbeat, romantic lyric in which Santelli underscores the importance of-the necessity for, in fact—small gestures of tenderness to make a relationship hum—"oh, please, just kiss my hand again before you leave"; "oh, please, just smile at me when you drive away"; "oh, please, just touch my face when you walk in the door." The innocence of it all is mesmerizing. Then consider the deceptive "Brown Haired Girl." Sung to her fingerpicked acoustic guitar accompaniment, it has a nursery rhyme quality to it, and Santelli's tiny, little girl vocal maximizes the song's childlike feel, but by the last verse we find the brown-haired girl is someone with whom her beau is cavorting, instead of being with her.

Santelli knows these two albums stand apart, and knows why: she got back to the basics, back to where she once belonged.

"I started getting back into singer-songwriter things again, because there was nowhere to play with the band anymore in New York, and I was feeling like I gotta do something else. So I started writing again, and I started a singer-songwriter session on Sunday nights, where I met Gina. There was a group of musicians that would get together on Sunday night at the Dubliner, and someone would come in with a new song, so we had to raise the bar and come up with something new the next week. Had to start writing, writing, writing, so it was a really good community that was going on. That's when I really started writing again, and it was that push from the other musicians. That's been going on for about five years now."

There's a weariness in Santelli's voice when she speaks of the long road she's traveled and the frustrations she's encountered. She admits to having "my ups and downs, that's for sure," but adds, "I feel pretty good where I am." Besides, the alternative, Master's degree or no, still does not present itself as more alluring.

"There's nothing else I'd rather do than this. I'd like to be able to tour and sell some records and live comfortably. That's my goal. To get the word out that I am here,

"I've been doing this, somebody listen to me. It's worth it, y'know?"

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: [email protected]

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: [email protected]

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024